How strong can hurricanes get?

There's a theoretical limit to the maximum sustained wind speeds of hurricanes, but climate change may increase that "speed limit."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

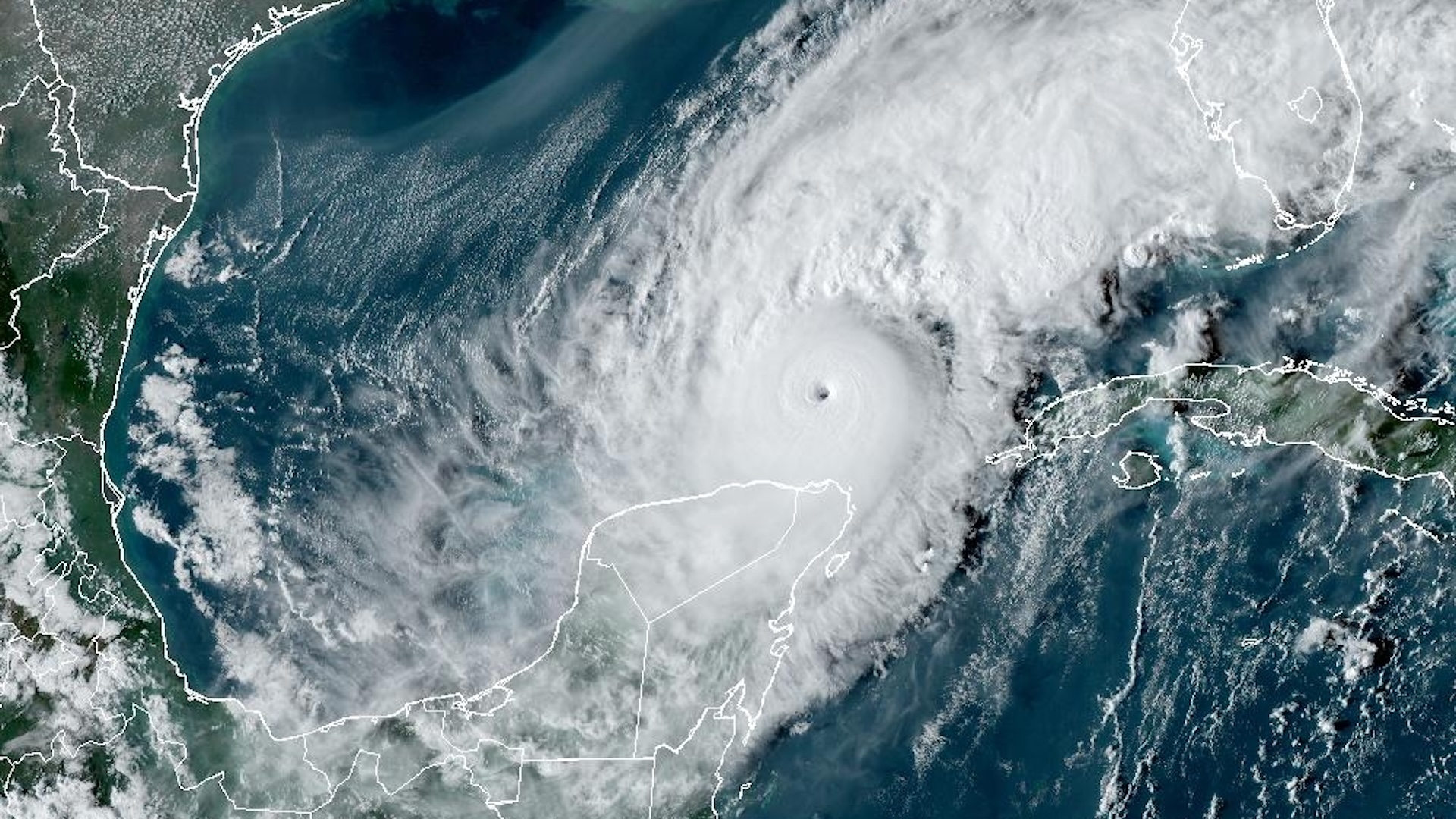

Hurricane Milton, which is expected to make landfall on the Florida coast Wednesday or early Thursday (Oct. 9 or 10), seemed to come out of nowhere: Just a tropical storm on Sunday, the hurricane roared into the Category 5 range Monday (Oct. 7), with sustained winds of 180 mph (298 km/h) before weakening slightly on Tuesday (Oct. 8).

But how close is Milton's sustained wind speed to the theoretical maximum? And is there a hard limit?

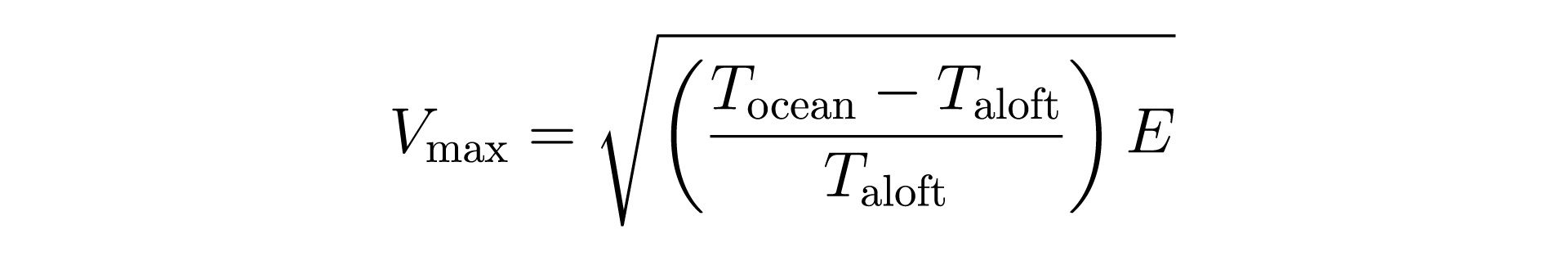

There is a "speed limit," on sustained wind speed, called maximum potential intensity, but it is not absolute: It is dictated by several factors, including the heat present in the ocean. Current calculations of the maximum potential intensity for storms typically peaks around 200 mph (322 km/hour).

But that may change in the coming decades as oceans warm and the climate changes. Already, the potential for strong storms has been rising over the past 30 years, said Kerry Emanuel, an emeritus professor of atmospheric science at MIT who developed the model. So have actual monster storms: Five storms on record have had winds exceeding 192 mph (309 km/hour). All of those have occurred since 2013.

"I think by the end of the century, if we don't do a lot of curbing, it's going to be closer to 220 [mph]," Emanuel told Live Science.

Related: We may need a new 'Category 6' hurricane level for winds over 192 mph, study suggests

What drives a storm

The speed limit on hurricane winds is relatively easy to calculate, said James Kossin, a climate scientist who is retired from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and now consults for the climate risk modeling agency First Street.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The fuel for the hurricanes is the heat they're drawing from the ocean," Kossin said. "The warmer the water, the more fuel is available."

Other factors help determine maximum potential intensity, such as the heat in the atmosphere and temperature of the cloud tops, which determines how quickly heat can move from sea surface to the top of a storm, and wind shear, which is the difference in wind speed and direction at different heights in the atmosphere. Too much wind shear can tear a storm apart, weakening it and preventing it from reaching its full potential. A study of storms between 1962 and 1992 found that only 20% of Atlantic cyclones reach 80% or more of their maximum potential intensity, though there is evidence that a greater proportion of storms are starting to get closer to their theoretical limit, Emanuel said.

As the oceans and atmosphere warm, storms are getting stronger. In 2020, Kossin and his colleagues reported that the proportion of major hurricanes increased by 8% per decade between 1979 and 2017. That means that as the climate warms, strong and rapidly intensifying storms like Milton may become shockingly common.

New hurricane categories?

Hurricanes are graded on the Saffir-Simpson scale, which ranges from Category 1 (starting at sustained winds of 74 mph, or 119 km/hour winds) to a Category 5 (starting at sustained winds of 157 mph, or 252 km/hour winds). This scale is incomplete, as it is based on wind speed and doesn't include damage from storm surge or flooding, which are deadlier than wind, Emanuel said.

The increasing probability of strong storms spurred Kossin and his colleague Michael Wehner of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory to suggest in February that the Saffir-Simpson scale may need a "Category 6," which would include storms with winds of more than 192 mph (308 km/h).

The researchers identified five storms that would already qualify for that category: Typhoon Haiyan (2013), Hurricane Patricia (2015), Typhoon Meranti (2016), Typhoon Goni (2020) and Typhoon Surigae (2021). Patricia was the most intense on record and the only one with winds over 200 mph. (The hurricane's winds reached 215 mph (345 km/h) but weakened to 150 mph (241 km/h) by the time the storm made landfall.)

Wehner and Kossin considered looking at hurricanes in a theoretical "Category 7" with winds over 229 mph (368 km/h). But their calculations showed there is currently a negligible risk of a storm that strong, Wehner told Live Science, so they left the possibility out of their paper.

No one really knows the maximum winds a hurricane could theoretically sustain if water temperatures keep rising, Wehner said. "In these really strong, distinct eyewalls where the winds are moving like crazy, these flows are very unstable," he said.

The exact dynamics of the eyewall aren't fully understood, Wehner said. Milton's weakening came after an eyewall replacement, which happens when a new band of thunderstorms forms around the storm's eye, choking off the moisture to the original eyewall. The shift deconcentrated Milton's energy, increasing the overall size of the storm but also diminishing its peak winds. It may be that, at extreme wind speeds, these storm-weakening phenomena become inevitable, but that isn't well understood, Wehner said.

"Say we're in a 4-degree warmer world, which is almost unthinkable, where the maximum possible intensity is well above 192 mph," he said. "Could these storms actually sustain themselves? I don't think we know."

Editor's Note: This story was updated at 9:45 a.m. EDT on Wednesday, Oct. 9 to correct the conversion of 200 mph to km/hour.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus