Spookfish Have World's Strangest Eyes

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

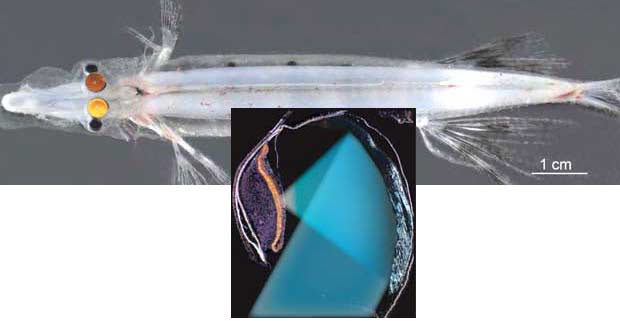

The four-eyed spookfish may have seemed strange enough. Now researchers say it doesn't really have four eyes. Instead, it is the known first vertebrate to use mirrors, rather than lenses, to focus light in its eyes.

“In nearly 500 million years of vertebrate evolution, and many thousands of vertebrate species living and dead, this is the only one known to have solved the fundamental optical problem faced by all eyes — how to make an image — using a mirror," said Julian Partridge from the University of Bristol.

While the spookfish looks like it has four eyes, in fact it only has two, each of which is split into two connected parts. One half points upwards, giving the spookfish a view of the ocean — and potential food — above. The other half, which looks like a bump on the side of the fish's head, points down. These diverticular eyes, as they are called, are unique among all vertebrates in that they use a mirror to make the image, Partridge and colleagues found.

Very little light penetrates beneath about .62 miles (1,000 meters) of water. Like many other deep-sea fish, the spookfish is adapted to make the most of what little light there is. It is flashes of bioluminescent light from other animals that the spookfish are largely looking for. The diverticular eyes image these flashes, warning the spookfish of other animals that are active, and otherwise unseen, below its vulnerable belly.

Although the spookfish was discovered 120 years ago, no one had discovered its reflective eyes until now because a live animal had never been caught.

When Professor Hans-Joachim Wagner from Tuebingen University caught a live specimen off the Pacific island of Tonga, members of his research team used flash photography to confirm the fish's upward and downward gazes.

Photographs looking down on the live fish produced eye-shine in the main tubular eyes that point upwards, but not in the diverticular eyes that point downward. Instead, these reflect light when seen from below.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It was when looking at sections of the eye that had been prepared for microscopy that Partridge realized that the diverticular mirrors where something exciting. The mirror uses tiny plates, probably of guanine crystals, arranged into a multi-layer stack. This is not unique in the animal kingdom (it's why silvery fish are silvery) but the arrangement and orientation of the guanine crystals is precisely controlled such that they direct the light to a focus.

A computer simulation showed that the precise orientation of the plates within the mirror's curved surface is perfect for focusing reflected light onto the fish's retina.

The use of a single mirror has a distinct advantage over a lens in its potential to produce bright, high-contrast images. That must give the fish a great advantage in the deep sea, where the ability to spot even the dimmest and briefest of lights can mean the difference between eating and being eaten.

The research will be published this month in Current Biology.

- How Your Eyes Work

- One Common Ancestor Behind Blue Eyes

- Fish News, Features and Images

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus