Major Volcano Eruptions Could Stymie Hurricanes

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

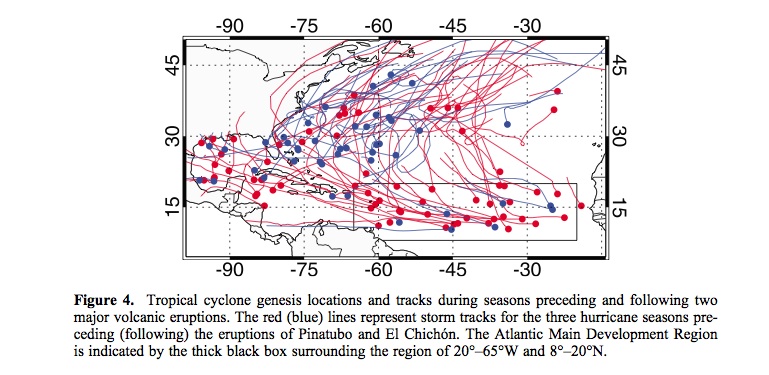

Eruptions of very large volcanoes can reduce the number and intensity of hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean for as long as the next three years, a study suggests.

The study, published last month in the Journal of Geophysical Research, looked at the impact of the 1982 eruption of El Chichón in Mexico and the 1991 eruption of Pinatubo in the Philippines. In the year following each eruption, both the frequency and intensity of hurricanes were reduced by about half, compared to the year prior, said study author Amato Evan, a climate researcher at the University of Virginia.

Large volcano eruptions like these can reduce global temperatures by releasing enormous quantities of sulfur dioxide into the layer of the atmosphere called the stratosphere. There the gas reacts with water to form tiny droplets, or aerosols, of sulfuric acid. These particles both reflect some light and absorb radiation, robbing the Earth's surface of some warmth.

Mount Pinatubo's eruption, for example, reduced global temperatures by about 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit (0.5 degrees Celsius) during the following year.

A growing body of research shows that when ocean surface temperatures are lower, hurricanes tend to be less intense, because they rely on warm waters as a source of fuel to drive convection, the storms' engine.

Volcanic one-two punch

By absorbing radiation, the eruptions also hurt nascent hurricanes because volcanic aerosols warm the lower stratosphere.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Hurricanes don't like that," Evan told OurAmazingPlanet. "When you cool the ocean surface and warm the atmosphere at a high level, it's a one-two punch, thermodynamically, for storms."

Hurricanes are powered by an upward movement of heat, so lower temperatures at the surface — and increased temperatures high up — reduce intensity, and also make it harder for storms to form, Evan explained.

Robert Korty, an atmospheric scientist at Texas A&M University, said he has seen similar effects in models simulating the last 1,000 years of climate. "But there is no upper-air data from centuries past against which those simulations can be compared, so this paper is an important contribution," said Korty, who wasn't involved in the research.

Although the waning of Atlantic cyclones was most pronounced in the year following these two eruptions, below-average hurricane activity persisted for a total of three years after El Chichón and Pinatubo, the study found.

El Niño complications

Uncertainties remain, however. Following both eruptions, there were strong El Niño events, which also tend to reduce hurricane activity. It's hard to separate the impact of the eruptions and the El Niño episodes; they both play a role, Evan said.

Then again, several studies suggest large eruptions can lead to El Niño events, said Ronald Miller, a researcher with NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, in New York City.

The presence of stratospheric volcanic aerosols can reduce the number of cyclones by changing the structure of winds over the ocean, Evan said.

Miller said the study could lead to more-accurate hurricane forecasts.

"If there were a very strong volcanic eruption, it is possible the storm season to follow may be repressed," Korty said. "Of course, even seasons that produce few storms can still be dangerous." For example, he said, there were only six significant Atlantic hurricanes in 1992 following the eruption of Pinatubo — an unusually quiet year. But one of these was Hurricane Andrew, the most destructive storm in U.S. history before Hurricane Katrina.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus