Eyeless Shrimp Discovered at Deepest Volcanic Vents

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists announced today (Jan. 10) some of the first details from the first expedition to the sunless, scalding-hot world of the deepest volcanic sea vents on Earth.

The researchers unveiled a remarkable list of discoveries: a newfound species of (mostly) eyeless shrimp, evidence that the deepest vent may also be the hottest on the planet, hints that giant slabs of a brilliantly colored mineral popular with Russian czars lie strewn nearby on the seafloor, and the suggestion that these seafloor hot springs are far more common than thought.

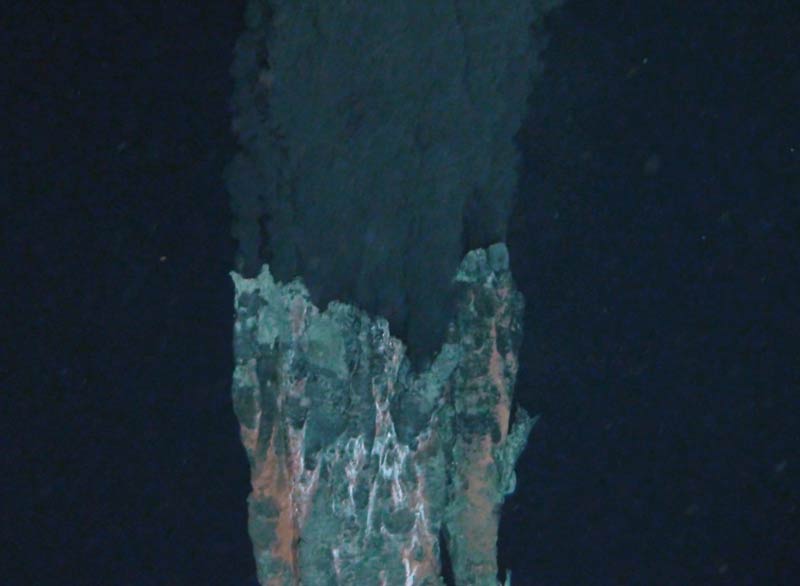

The announcement comes nearly two years after researchers aboard the British research vessel James Cook crowded around video monitors and became the first humans to glimpse an extraordinary sight 3 miles (5 kilometers) below them, at the bottom of the Caribbean Sea: slender, rocky spires towering 20 feet (6 meters) above the seafloor, spewing forth a sooty jet of metal-rich fluid some 3,600 feet (1,100 m) high.

Article continues below"It was a very emotional moment on board — and honestly, there were some tears. It was an overwhelming moment of marvel at our world," said marine biologist Jon Copley, with the University of Southampton in England.

The researchers moved their remote-control vehicle toward the site, known as a black smoker, and a living, wriggling world sprang into view — swarms of shrimp, delicate anemones — "and we were just jubilant, really, and started to explore it further," Copley told OurAmazingPlanet.

Unexpected find

The revelations from the expedition, published today in the journal Nature Communications, come at an exciting time. An expedition is at sea this week, aiming to take the first temperature measurements of the deep-sea vents, and take an even wider variety of samples. [See the eyeless shrimp]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Evidence of the sites first surfaced in 2009, when an American-led expedition sniffed out the chemical signature of two hydrothermal vent systems — seafloor chimneys that, fueled by the furious heat of Earth's interior, spew forth a scalding soup of chemically altered seawater — in the Mid-Cayman Rise, a deep gash in the seafloor just south of the Cayman Islands.

It's a site known as a mid-ocean ridge, where two tectonic plates are being wrested apart as fresh seafloor, extruded from the Earth's insides, is shoved between them.

The Mid-Cayman Rise, a rift in the seafloor 70 miles (110 km) long and more than 9 miles (15 km) across, is the deepest mid-ocean ridge on the planet, plunging to nearly 20,000 feet (6,000 m) in places. It's also one of the slowest, widening by just over half an inch (15 mm) per year. [Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench]

Following the discovery of the vents, Copley and his colleague Doug Connelly, a geochemist at the National Oceanography Center in Southampton, led an expedition that was the first to visit and take samples near the two undersea hot springs.

The shallower of the two vents, dubbed the Von Damm, lies 7,500 feet (2,300 m) down, near the summit of an underwater mountain called Mount Dent. The second vent, the world's deepest at 16,400 feet (5,000 meters), is known by two different names, Beebe and Piccard, for William Beebe and Jacques Piccard, both pioneers of deep-sea exploration.

New life

Although the sites aren't far apart — just about 12 miles (20 km) — the Beebe site is twice as deep, with twice the pressure, yet the team discovered the same species of shrimp living in both places.

The newfound shrimp, dubbed Rimicaris hybisae for HyBIS, the deep-diving vehicle used to fetch them, sport a light-sensing organ on their backs that resembles the angular robot-face logo of the evil Decepticons, the bad guys in the Transformers universe.

It's an appropriate feature for a creature with some remarkable shape-shifting adaptations of its own.

"They do have eyes in their early stages, but then they lose them," Copley said.

Based on similar species seen at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Copley said, it appears likely that the shrimp begin life in the deep, but twilit, layers of the ocean, and have typical shrimp eyes, at the end of stalks. "Females move away from vents when brooding," Copley said. "Right by a black smoker probably isn't a good place to breed your embryos."

The young shrimp likely feed on a snow of decomposing material drifting down from the sunlit world above — "so they're feeding on photosynthetic-derived material," Copley said, a contrast from their chemosynthetic diet — one fueled by chemical reactions driven by the Earth's interior heat, instead of the sun — later in life.

As adults, the shrimp return to the vents and undergo a metamorphosis, losing their eyes and developing the light sensor on their backs, which can do little more than tell the 1-inch-long (3-centimeters) creatures if there's a light source nearby. (Although their environment is pitch-black to human eyes, the hot vents emit an infrared glow.)

At their deep-sea homestead, the shrimp feed on gardens of bacteria they cultivate on their own bodies, a strategy also used by yeti crabs recently discovered at hydrothermal vents in the Antarctic.

Super what?

There was one big difference between the two shrimp populations, scientists said. In contrast to the pristine white creatures at the Von Damm site, the shrimp at the Beebe site were a grubby shade of orange, dyed by a fine dusting of rust.

Seawater samples show that the Beebe vent's fluid is extremely rich in metals — among them iron, which explains the rusty shrimp. (When iron oxidizes it turns to rust.)

This hints at an alluring possibility, Connelly said. The vent might provide scientists with one of their first glimpses in the natural world of water in a supercritical-fluid state — water at such extreme high temperatures and under such high pressure that it starts to behave in weird ways

"The physics of the system behaves quite strangely," Connelly said. It appears that supercritical water can act as a conduit for elements and valuable metals, preferentially stripping them from rocks and ferrying them from inside the Earth, "so there may be enriched mineral deposits around these sites," he said.

This type of natural strip-mining likely occurs deep inside other hydrothermal vent sites, but, once the fluid rises to a depth where the pressure diminishes, stops before the fluids come blasting out through the seafloor.

"Here we may be seeing that [fluid] getting right to the surface," Connelly said.

Regal signposts

The Beebe/Piccard site is about 3,000 feet (900 m) deeper than any vent ever discovered. At such depth, it could be that the pressure is so intense that the water retains its weird, mineral-mining properties in a place where — with great difficulty — humans can watch.

It could be "a window to what normally happens in the deeper sub-seafloor," Connelly said.

Another tantalizing indication that the Beebe site could be just such a window, Connelly said, came when the camera spied an unmistakable hue on the seafloor nearby — the bright, lustrous green of malachite, a precious mineral strewn generously about royal residences from Versailles to St. Petersburg in forms as various as tables, urns and columns.

Although he said that colors in the deep sea can be deceptive, and he has no way of knowing for sure until the substance is sampled, "to see that color green — it was very tantalizing."

"We saw sheets of it on the seabed, which was amazing," Connelly said. "It's a very distinctive color, so the geologists got very excited, but we couldn't grab a piece," he said. "No doubt our colleagues out there will find a piece," he added.

Big answers, new questions

Both Connelly and Copley said that, although it's not as deep, the Von Damm vent was almost the bigger surprise. The discovery of the site, perched on a mountain top several miles away from the Mid-Cayman Rise's main volcanic activity, was a shock, and one with big implications.

"There may be a lot of vents out there that we've missed," Copley said. From a biological standpoint, he said, this could mean there are a lot more stepping stones flung around the world's oceans that might allow species to leapfrog from one hydrothermal vent site to the next.

A 2010 NOAA expedition found tube worms at the Von Damm site, a first for a hydrothermal vent site in the Atlantic, and yet another sign that animals travel among vent sites in mysterious ways.

Connelly agreed, and said that, although the expedition was immensely informative, it also raised a lot of very big questions. Some, such as the temperature of both the vents, will likely be answered in the coming days. Others will require years of research and further exploration.

For him, Connelly said, being able to look but not touch much of the unexplored world he saw unfold before him in 2010 was exhilarating.

"It was frustrating as well — only ever getting to half the answer you want to," he said.

"But that's what makes science great, isn't it? There are still questions to answer."

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus