Humans Show Empathy for Robots

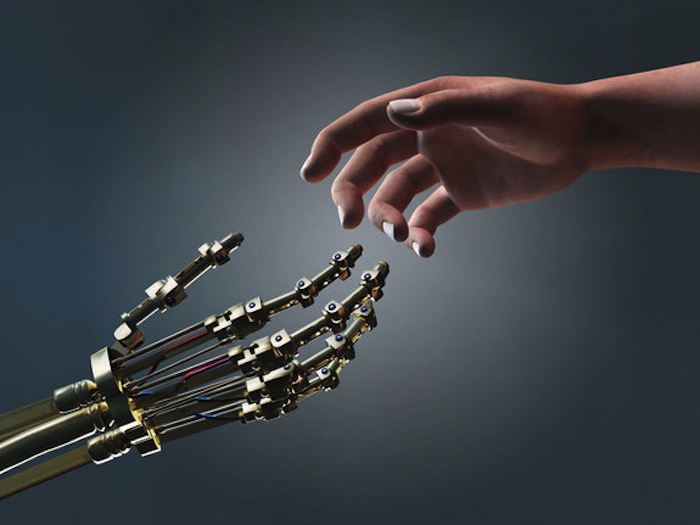

From R2-D2 in "Star Wars" to Furby, robots can generate surprisingly humanlike feelings. Watching a robot being abused or cuddled has a similar effect on people to seeing those things done to a human, new research shows.

Humans are increasingly exposed to robots in their daily lives, but little is known about how these lifelike machines influence human emotions.

Feeling bad for bots

In two new studies, researchers sought to measure how people responded to robots on an emotional and neurological level. In the first study, volunteers were shown videos of a small dinosaur robot being treated affectionately or violently. In the affectionate video, humans hugged and tickled the robot, and in the violent video, they hit or dropped him. [5 Reasons to Fear Robots]

Scientists assessed people's levels of physiological excitation after watching the videos by recording their skin conductance, a measure of how well the skin conducts electricity. When a person is experiencing strong emotions, they sweat more, increasing skin conductance.

The volunteers reported feeling more negative emotions while watching the robot being abused. Meanwhile, the volunteers' skin conductance levels increased, showing they were more distressed.

In the second study, researchers use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to visualize brain activity in the participants as they watched videos of humans and robots interacting. Again, participants were shown videos of a human, a robot, and, this time, an inanimate object being treated with affection or abuse.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In one video, for example, a man appears to beat up a woman, strangle her with a string and attempt to suffocate her with a plastic bag. In another, a person does the same things to the robot dinosaur.

Affectionate treatment of the robot and the human led to similar patterns of neural activity in regions in the brain's limbic system, where emotions are processed, fMRI scans showed. But the watchers' brains lit up more while seeing abusive treatment of the human than abuse of the robot, suggesting greater empathy for the human.

"We think that, in general, the robot stimuli elicit the same emotional processing as the human stimuli," said lead study author Astrid Rosenthal-von der Pütten of the University of Duisburg Essen, in Germany. Rosenthal-von der Pütten suspects that people still have greater empathy for humans than robots, as evidenced by the stronger effect of watching violence toward the human than the robot.

Still, the study only assessed people's immediate reactions to the emotional cues, Rosenthal-von der Pütten said. "We don't know what happens after the short term," she said.

Human-robot interactions

That humans would show empathy for the robot is not surprising, because the bot looked and behaved like an animal, roboticist Alexander Reben, founder of the company BlabDroid, LLC and a research affiliate at MIT, told LiveScience. Reben, who was not involved in the recent study, himself builds small cardboard robots that tap into the human affinity for cute creatures.

Some people find the idea of humans empathizing with robots concerning. But Reben compared trends in robot development with breeding dogs for companionship. "We have been doing this for millennia," he said. "I think we're doing the same thing with robots."

Humans have been known to show empathy for robots in a variety of contexts. For instance, soldiers form bonds with robots on the battlefield. Other research suggests that humans feel more empathy for robots the more realistic they seem, but not if they're too humanlike.

As robots become more and more ubiquitous, understanding human-robot interactions will take on increasing importance, Rosenthal-von der Pütten said.

The new research will be presented in June at the International Communication Association Conference in London.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

![In new research, volunteers showed empathy while watching videos [See Video] of a small dinosaur robot being treated violently.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/MbSz5XWnAuFzLJNGfbxVU5.jpg)