Hidden Tracks: Whale Songs Found in Seismic Recordings

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A rich, but untapped trove of whale calls hides in decades of recordings collected by geologists surveying the ocean floor.

The recordings come from seismic studies that shoot powerful air guns underwater to jiggle the Earth and learn more about its makeup. Sensors listen to acoustic waves in the water before, during and after the shots, capturing the reflections from the ground. But they can also pick up songs from any passing marine life that chats on the same frequency — fin whales and blue whales, in this case.

Extracting those squeals, squeaks and moans from the recordings could greatly improve scientist's understanding of the air gun's effects on whales. The noise could potentially confuse or even harm marine life, according to researchers at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in Woods Hole, Mass. The calls may reveal how whale behavior changes in response to the sudden, sharp bursts in many different settings.

"We're really excited about the potential for it," said Laela Sayigh, a WHOI marine biologist. "There is a treasure trove of data."

Funding needed

The goal: Create a computer algorithm to extract the whale calls from data collected during a 2002 research cruise in Mexico's Gulf of California. The Gulf is a birthing ground for blue whales, and teems with marine life. Researchers will analyze whale behavior before, during and after the air gun blasts.

The cruise included onboard observers to track the effects of airguns on marine life, so scientists could potentially link calls to individual animals by matching the calls with those observations.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We have a huge amount of data that can say, 'Did they change their behavior? Did they stop feeding? Did they stop talking? Did they talk louder?', and that's what we want to know," said WHOI seismologist Dan Lizarralde.

For now, the project is only an idea, because Sayigh and Lizarralde have no money for the research. Woods Hole turned the researchers down for an internal grant. This month they will apply for a grant from the Navy, which uses sonar and underwater explosions during training, and funds research exploring the effects of ocean noise on marine life.

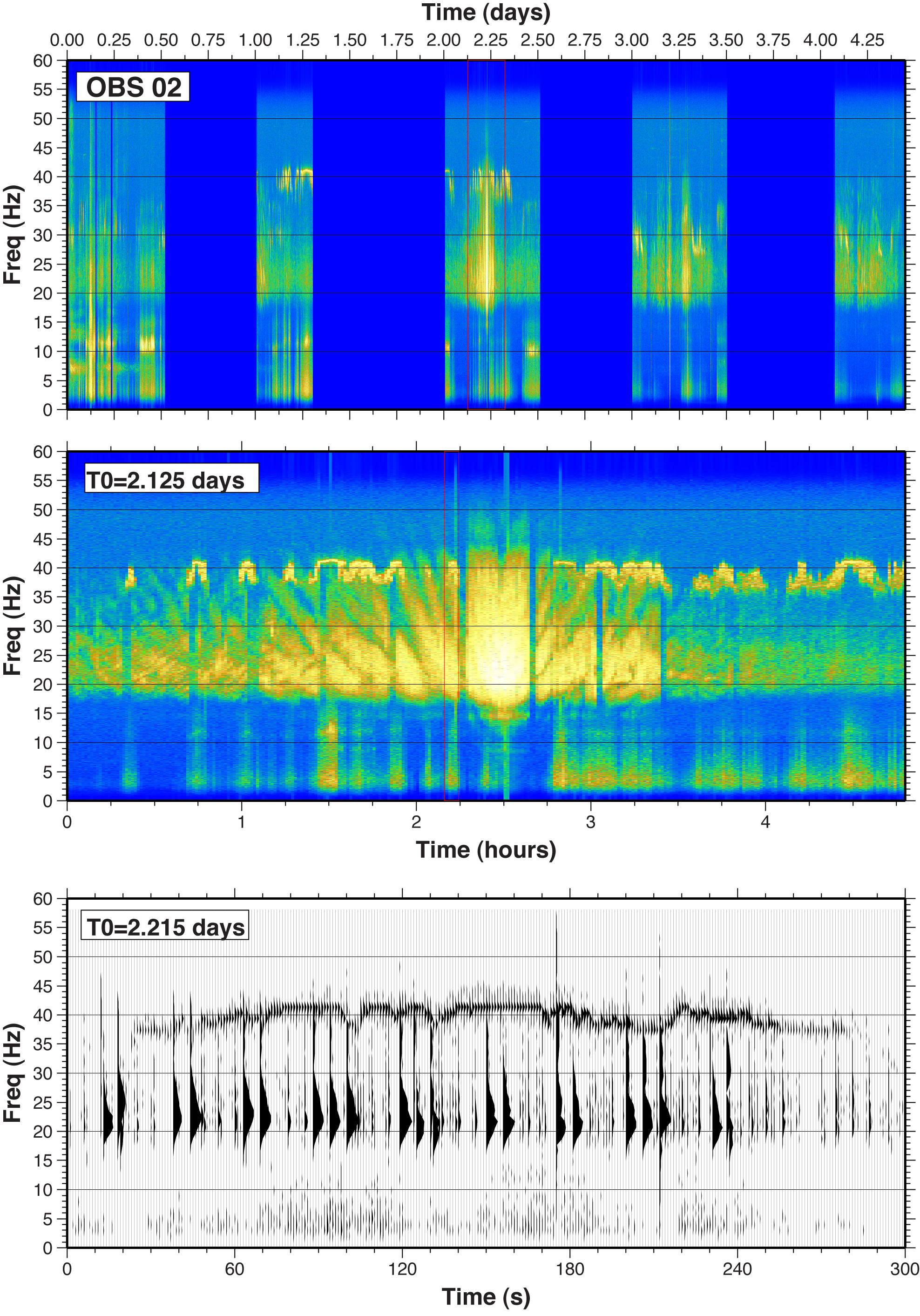

Whale calls recorded during a seismic survey in the Gulf of California.

Top: This spectrogram of ocean sound was recorded by a hydrophone during an air gun seismic experiment in the Gulf of California in 2002. Color indicates the loudness of the sounds, with yellow the loudest. Dark blue represents when the air guns were not being fired. The bright yellow signals ranging from about 17 to 30 Hertz are calls from fin whales, according to WHOI researchers.

Middle: A 5-hour span from the first panel shows more detail in the sounds. The brief blank periods between are short silences between intense whale call activity.

Bottom: A 5-minute span from the second panel show the presence of at least two fin whales, one much close to the hydrophone than the other.

CREDIT: Dan Lizarralde/WHOI

Ocean noise and marine life

Parking hydrophones underwater to listen to whales is not new, but looking for the calls in seismic survey data is. As long as whales are calling, this precise method of monitoring them could track individuals and groups of whales through the water, showing researchers how the whales react to the blasts, Sayigh said.

Whale researchers have tracked the animals with underwater devices for decades, said Susan Parks, a bioacoustics expert at Pennsylvania State University who studies right whales with underwater recordings. "This is proven technology," she said. "I think it's an interesting idea, and it's really quite promising," she said. [Video: Listen to whale calls]

Dorian Houser, director of bioacoustical research for the National Marine Mammals Foundation, said Sayigh's and Lizarralde' project has potential. "We are really in the dark in a lot of the response of the animals to [ocean noise]," Houser told OurAmazingPlanet. "There's a big push to try and understand these exact questions: How does a whale's behavior change when they are exposed to these exact sounds, and what is the consequence?"

Sayigh thinks the project may also answer questions about the beaching of two Cuvier's beaked whales. Those whales came ashore while the 2002 research cruise that collected this data was in the Gulf, and the cruise was accused of playing a role in the deaths. "They know the exact amplitude of all their shots, and could extrapolate the likely location for the whales," Sayigh said.

If Sayigh and Lizarralde succeed in getting funding, there's a huge archive of seismic data waiting for future studies. Since 1999, all recordings from research cruises like Lizarralde's, funded by the National Science Foundation, go into an open-access archive called IRIS, the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology.

"We'll keep trying," Lizarralde said. "I really want to see what the behavior is associated with these air guns.

"I've convinced myself from observations that the whales are completely uninterested, that it's probably annoying but not damaging, but I'd like to know that better," he said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook or Google +. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus