Survival Odds Grim for Native Plants Fighting Invaders

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

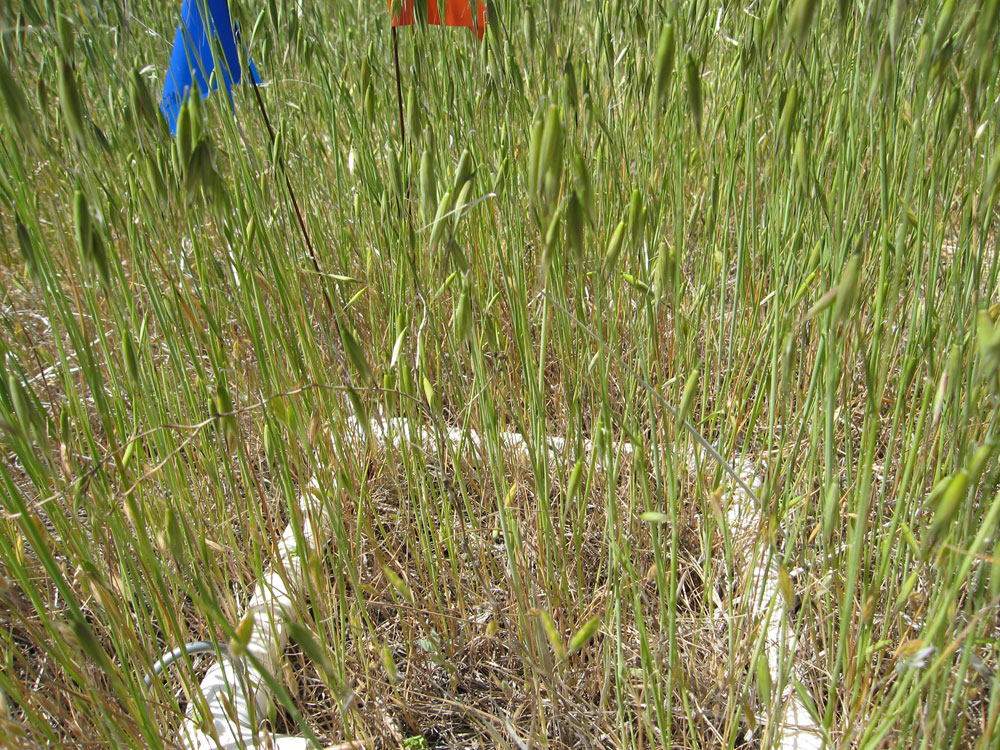

Invasive species are winning in the battle for survival against some native plants in a California reserve, according to a new study.

The research has troubling implications for plant hardiness, the scientists studying the plants said. While some researchers have believed the invaders merely supplement the native ecosystem, the new findings, published online earlier this month in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, show that a few of the original plants could die out in a few hundred years.

"What we see is a serious invasion, meaning that as one or more invasive species start to become abundant, the native plants shrink down in their habitat," said ecologist Benjamin Gilbert, who did field research during a temporary appointment at the University of California. He is currently with the University of Toronto.

Among other experiments, Gilbert and co-author Jonathan Levine planted plots of several native species, including the native flower Lasthenia californica, at the Sedgwick Reserve in the Santa Ynez Valley near Santa Barbara. Researchers then observed the plants' growth and modelled the long-term trend for the plants' survival based on the experimental results.

In general, Levine and Gilbert noted that the seedlings did not do very well in areas dominated by "exotic" grasses, such as Avena fatua, and that the population sizes of the native species are shrinking to critical levels.

Researchers have found that the number of total species in an area increases as exotics take hold and natives cling on to life. However, the native species are restricted to small "refugia," or isolated populations, located far apart from each other, which could hurt their long-term survival, Gilbert said.

Such isolated patches make the plants are more susceptible to damage frombeing hurt by disease or fire; plus, it's harder for them to disperse seeds.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The native species are pushed out of the best habitat," Gilbert told OurAmazingPlanet. "The analogy for people is being taken off a really good diet — it's getting them by, [but] it's not optimal."

Native species that have adapted to more challenging environments, such as rocky conditions, tend to fare better. "In this case, the only reason the natives seem to do well in these patches is it is so crappy for the invasives," Gilbert said.

As for protecting the native species, pesticides sometimes do more harm than good. It might be more effective, Gilbert suggested, to create a "corridor" of suitable habitat between patches of native species, which would help them again colonize larger areas.

One challenge, though, is that most of the native species develop naturally in small areas, although the invasives push them to sites that are much smaller than usual. This makes it difficult to study the impact of invasive species or to encourage the natural grasses and flowers to expand their habitats.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace or on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus