500-Million-Year-Old Animal Looked Like a Tulip

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

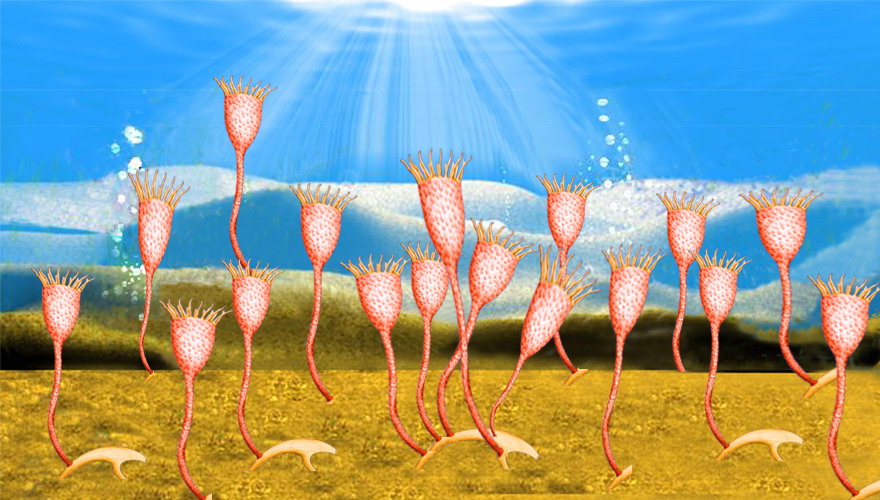

An ancient sea animal that looked like a flower had its anus right next to its mouth, a new fossil study finds.

The research reveals that this odd marine creature was likely an ancestor of a group known as the entoprocta. Previously, the oldest fossil entoprocta came from the late Jurassic, about 145 million years ago. The new fossils date all the way back to the Cambrian, about 520 million years before the present.

That is near the so-called Cambrian Explosion, when most of the major lineages of animals appeared on the scene, as did complex ecosystems. Some odd animals emerged during this time, such as bizarre shrimplike monsters called anomalocaridids that could grow up to about 6 feet (1.8 meters) in length; a 515-million-year-old predator with compound eyes containing 3,000 lenses; and a 50-legged arthropod that skittered along the seafloor of what is now Canada.

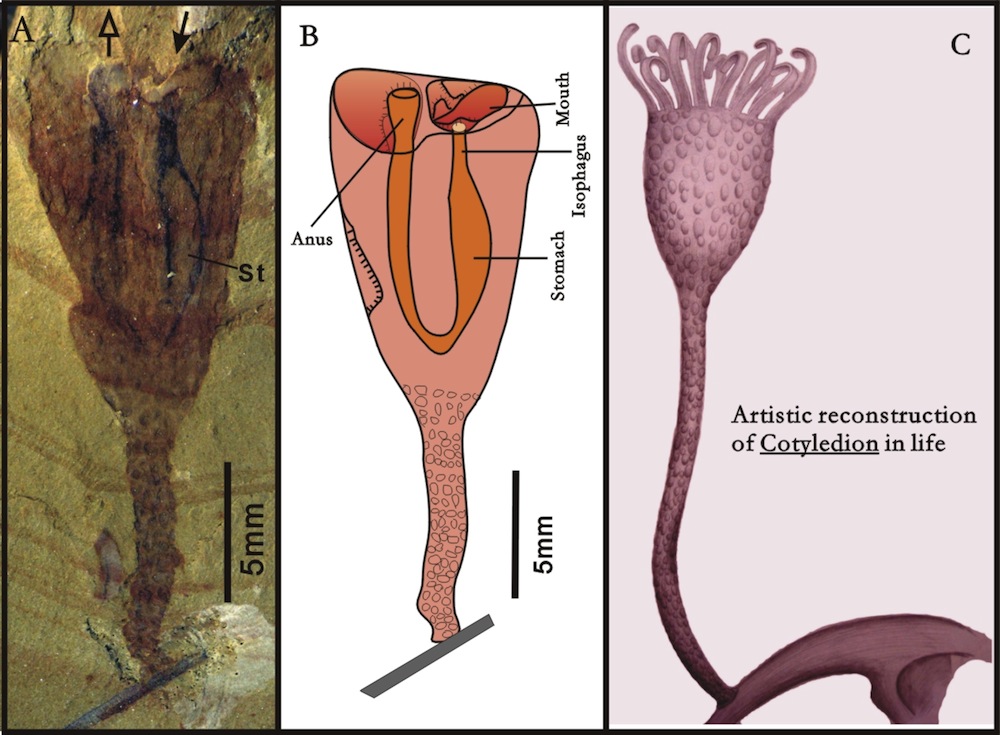

The newfound species, Cotyledion tylodes, has been analyzed before, but the discovery of hundreds of new specimens allowed researchers led by Zhifei Zhang of Northwest University in Xi'an, China, to take a more detailed look. The team analyzed 418 specimens from Yunnan, China. [The 10 Weirdest Animal Discoveries]

They found that C. tylodes lived a lifestyle fixed to one spot, filtering water through a ring of tentacles that surrounded its mouth — and its anus. The two openings sat right next to one another, connected by a U-shaped gut.

That gut proved that the previous classification of C. tylodes as a cnidarian, or jellyfishlike creature, was wrong, the researchers report today (Jan. 17) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Instead, the flowerlike filter feeder was likely an early entoproct, Zhang and colleagues found. The body pattern is almost identical, though the ancient version grew to a length of 0.3 inches to 2.2 inches (8 to 56 millimeters), while today's entoprocts are comparatively tiny at between 0.004 inches and 0.27 inches long (0.1 to 7 mm).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Another big difference between C. tylodes and modern entoprocts is on the outside. Unlike what is found in living entoprocts, the stem and flowerlike feeding cup of the ancient creature were covered by tiny hardened protuberances called sclerites, which may have formed a sort of hard exoskeleton for the creatures.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus