Oldest Gold Artifact in Americas Found

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

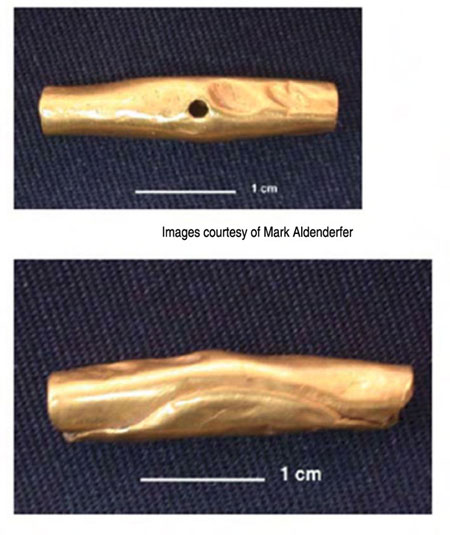

A necklace of gold and turquoise-colored beads at an ancient hunter-gatherer burial site in the Andes Mountains is the oldest crafted gold artifact known in the Americas and challenges the idea that only complex societies could produce such displays of wealth and prestige. The nine-bead necklace was found at the base of an adult skull in a grave at Jiskairumoko, a primitive hamlet once occupied by a group of hunter-gatherers near Peru's Lake Titicaca. The burial site dates to between 2155 to 1936 B.C., before more advanced societies, such as the Chavin, Moche and Inca, flourished in the region. Gold and other finery were symbols of wealth and status in these societies (as they still are in ours). "Gold certainly is one of those things in human history that has attracted the eye," said Mark Aldenderfer of the University of Arizona, the leader of the team that found the necklace. "People see it as something unique and different." But such rich adornments hadn't been documented by archaeologists in more primitive societies. The discovery of the necklace, detailed in the March 31 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests that these primitive people were in the middle of the transition to a more structured, agrarian society and that their metal-working abilities may have been underestimated. "This is, for us, signaling this interesting social process that's really part of a dramatic transformation towards some kind of [social] inequality," Aldenderfer said. Crude craftsmanship After carefully extricating the beads of the necklace from the soil, Aldenderfer and his team arranged the beads on a string as the team thinks the necklace likely looked, with long, cylindrical gold beads interspersed with small circular beads made of a turquoise-colored mineral. Though the necklace seems to have a planned design, the craftsmanship is still crude — it would be a few hundred years before dedicated metal-working craftsmen emerged. "This isn't fine work by any means," Aldenderfer said. The method Aldenderfer suspects the original maker used was simple: A gold nugget about an inch or so long would have been hammered with a stone pestle and bowl to flatten it. "And when you get that thing flat, the next stage of the process seems to be that you would find some resistant, tubular object … and simply begin wrapping this thin piece of gold around that wooden object and keep pounding it around until it’s the tubular shape that the beads have," Aldenderfer told LiveScience. "This is not hard to do, but it did take some thinking and care and foresight in order to make it properly," he added. The beads were so easily pounded into shape because "these are nuggets that were 93 to 95 percent pure elemental gold, and elemental gold is really soft," Aldenderfer explained. The gold's exact origin is uncertain, but native gold deposits are found in Peru about 125 miles (200 kilometers) away from the burial site. Society in transition The discovery of gold jewelry in such an early site was a surprise to Aldenderfer. Though people have been adorning themselves since before even this early society, gold bling wasn't thought to have developed until much later. "Everything in the New World that we know about in terms of where gold is used is always in the context of socially complex peoples," Aldenderfer said. The people who dwelled at Jiskairumoko had not fully settled down; they were hunter-gatherers who stored some food and had begun to domesticate some tubers and grains. "These folks are right in the middle of the process of becoming fully sedentary, so in other words, they're transiting from being mobile hunter-gatherers at some frequency to being people who are being mostly sedentary," Aldenderfer said. Previously, anthropologists have thought that the requirements for the social emergence of a craft tradition such as jewelry-making included a more secure economic base and complex culture. The use of gold by this group at Jiskairumoko indicates a society that was just beginning to show signs of developing an elite class. There weren't necessarily clear leaders with absolute authority, but they had some kind of prestige within the society, Alderderfer thinks. "These are people who are using this gold as a means by which to enhance their prestige and their status and to kind of push themselves forward by the kind of contacts they have with others to show, 'I'm an important person, you should trust me, you should listen to me.'," Aldenderfer said. "So clearly this did function as a personal adornment for this person, but the fact that it's so valuable and so rare and so unique, that says a lot about the person that it was buried with or the social group to which they belonged," he added.

- Gold Quiz: From Nuggets to Flecks

- The Last Gold Rush and the Real Cost of Bling

- Top 10 Ancient Capitals

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus