'Supermice' Invade Europe with Mighty Sperm

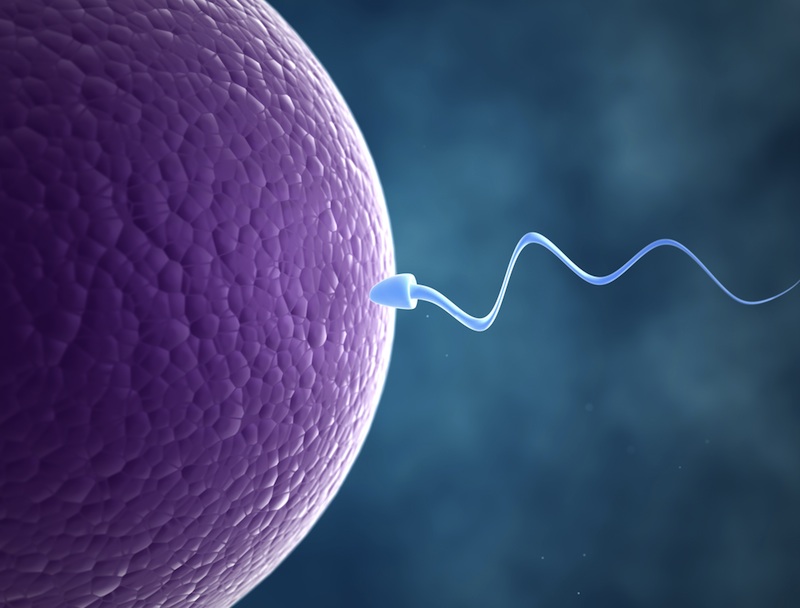

The male chromosome of an Eastern European house mouse has infiltrated Western Europe, creating a hybrid strain of "supermice" with extra-high sperm counts.

Normally, hybridization, when two subspecies mate to produce offspring, results in decreased sperm strength in the offspring. But when the western mouse Mus musculus domesticus picks up a male, or Y, chromosome from the eastern mouse Mus musculus musculus, the result is a strain of mice with higher-than-normal sperm counts that now thrives in the Czech Republic and the Bavarian region of Germany.

The results have implications for understanding the causes of high and low sperm counts in men, said study researcher Stuart J.E. Baird, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Porto in Portugal.

"It seems likely the genetic variants which have been uncovered in nature by our work will be taken and bred into lab mice so that their precise effects can be teased apart under controlled conditions," Baird told LiveScience. He said he will soon be joining the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic to continue research on the hybrid mice.

Mixing and mating

Mus musculus domesticus and Mus musculus musculus are separate subspecies, but they retain the ability to interbreed, and have been doing so for at least 6,000 years. Hybrid domesticus-and-musculus mice are found in what's called the European House Mouse Hybrid Zone, a 12-mile-wide (20 kilometers) swath stretching from Norway to Bulgaria. This front of mouse hybridization is the biological equivalent of an atom smasher, Baird said: It throws two species together in natural conditions and allows scientists to watch what happens next.

In the Czech-Bavarian region of this zone, researchers have started spotting more and more male mice of the western domesticus species with the Y chromosome of the eastern musculus mouse. In other words, male domesticus mice, in mating with their eastern brethren, have produced offspring with the eastern male chromosome.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The genetic determination of sex in mice works the same way it does in humans: The female contributes an egg, which always contains one X chromosome. The male contributes sperm, which contains either an X or a Y. If two Xs meet, the result is a female with an XX genetic profile. If an X and a Y meet, it's a boy. [10 Wild Facts About the Male Body]

Strong hybrids

Baird and his colleagues trapped 212 mice in the Czech-Bavarian hybrid zone and tested their sperm motility and sperm count. They also genotyped the mice to see if they were Eastern, Western, or a hybrid of both.

The results revealed that western domesticus mice that had picked up an eastern musculus Y chromosome in the process of hybridization had higher sperm counts than either original subspecies. On average, the mice with the invasive Y chromosome had more than 6 million more sperm present than mice with the original Y.

"We showed how the eastern males' Y chromosome has crossed the front, replacing the Y chromosome in 'native' western mice," Baird said. "It could invade because western males carrying the invading Y have higher sperm counts."

The discovery explains an overall increase in sperm count in mice of this region, Baird added.

"One possibility is that this is just the first of a cascade of effects we will see as the barrier between the species is broken down," he said.

Studying the genetic differences in the Y chromosome that give rise to these variations in sperm count could help researchers understand the genetic roots behind low human sperm count, Baird added. It's an important question, given some anecdotal reports that men's sperm count is on the decline globally.

But the triumph of the mousy Y chromosome won't necessarily spread, Baird said. Different local populations may have genetic variations that make it harder for the invading Y to take hold.

"Our team and others are there to watch what happens," said Baird, who, along with his colleagues, reported the results today (Oct. 9) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. "The Y chromosome invasion is perhaps the most exciting finding yet — but what happens next for hybridization of the mice?"

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.