Canada Unveils Next-Generation Robotic Arms for Spaceships

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The Canadian-built robotic arms built for NASA's space shuttle fleet and the International Space Station are about to get two new siblings.

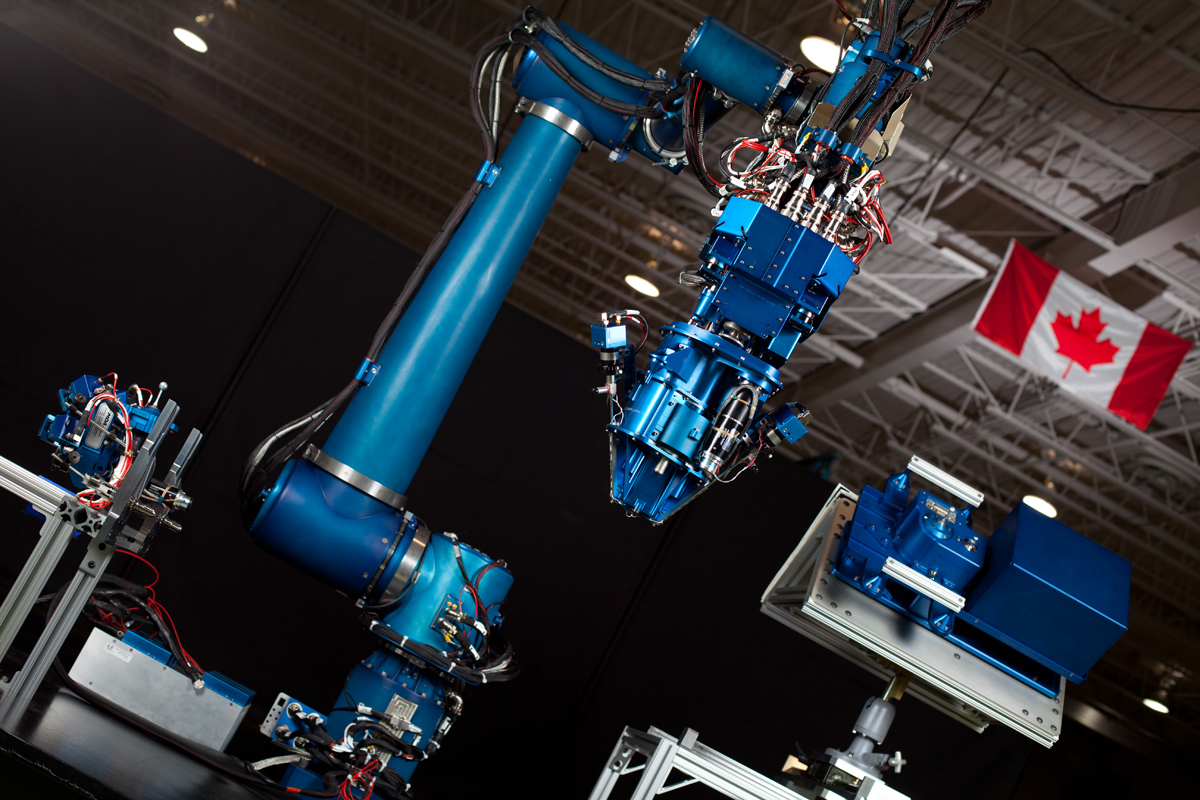

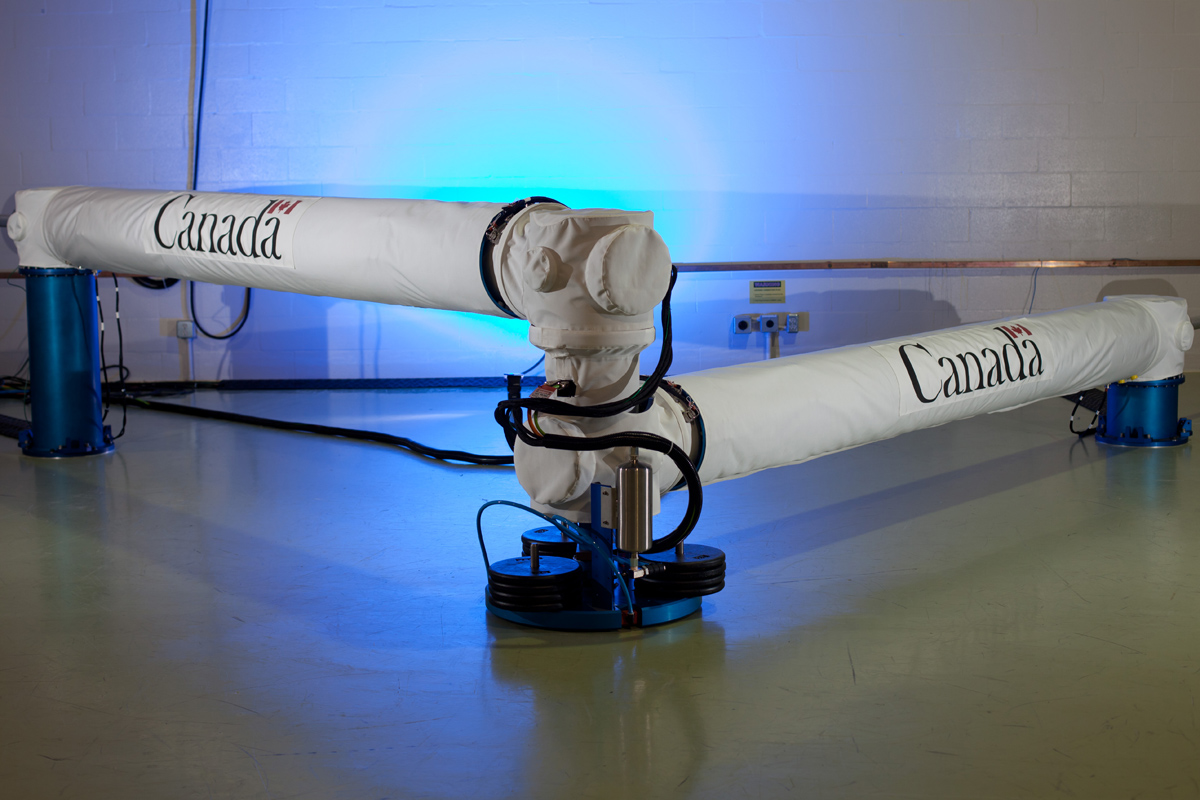

Last week, the Canadian Space Agency showed off the Next-Generation Canadarm (NGC) prototypes, which were unveiled after three years of development at Canadian company MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates. The mechanical limbs are the successors to the shuttle fleet's Canadarm and station's Canadarm2, which played pivotal rolls in the station's construction for more than a decade.

The CSA and MDA plan to use this technology to position Canada for newer space business opportunities in areas such as in-orbit refuelling of satellites, said Gilles Leclerc, the agency's director-general of space exploration.

"We prepared all these new systems so that we will be well-positioned for the next thing in space," Leclerc said.

However, the Canadian government's $53.1 million contribution to the arm project (as well as supporting testbeds and simulators) has only brought them to the prototype stage so far. The arms will require more money for launch configurations and a ride to orbit.

Fuelling competition

One of the prototype arms spans 49 feet (15 meters), the same length as the space station's Canadarm2. But the new arm is lighter and has two sections that telescope into each other. This makes it more suitable to fold up inside the smaller spacecraft of the future. [Photos: Building the International Space Station]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The other NGC prototype arm is a miniature, at 8.5 feet long (2.58 meters). Like the station's Dextre robot, which it is modelled after, it will be able to refuel satellites, grapple tools and manipulate items such as blankets that cover satellites.

Manufacturer MDA has spent several years touting the benefits of satellite refuelling, which the company says would save money since satellites could be kept aloft longer if they can receive more after launch.

In March 2011, MDA signed a $280 million agreement with Intelsat SA to advance this concept, but the deal was scuppered in January 2012 after receiving lukewarm interest from potential customers.

NASA is also considering robotic refuelling. There is debate among Canadian space circles as to whether MDA could contribute to NASA's project, since it is a Canadian company.

Future government funding?

The CSA's contribution to NGC came from one-time stimulus funding it received in the federal budget between 2009 and 2011. Now, the agency is trying to figure out its priorities in the next few years amid large budget cuts, and with future government funds to NGC in flux.

The Canadian government recently began cutbacks to address its deficit, and CSA was among the affected departments. CSA faces a 25 percent budget drop to $315.3 million (CDN$309.7 million) in 2013-14. The year after, money will fall even further to $294.3 million (CDN$289.1 million.)

The agency is doing an internal review to determine its priorities with the lesser budget, said Leclerc. Work on the International Space Station will come first, since the Canadian government agreed to take part in the station until 2020, he said.

CSA's approach will be to "maintain signature technology to develop" while placing resources where it can, he said.

The agency's priorities will also be determined by an external review of the Canadian aerospace sector that should be submitted to the government in the coming months.

Canadarm's legacy

Canadarm has a cherished spot in Canadian space history because its success eventually led to the astronaut program.

The first Canadarm flew in space in 1981 on STS-2, the second space shuttle mission. NASA was so impressed by the robotics that it invited the Canadians to fly payload specialists on future shuttle missions.

The first Canadian, Marc Garneau, flew in 1984. He has since called it a "pay-to-play" arrangement.

Subsequently, Canada provided four more Canadarms to NASA between 1981 and 1993 (one was lost on Challenger), as well as the next-generation Canadarm2 that was installed on the space station in 2001.

Over the years, the arms have grappled satellites, hoisted astronauts and assisted on construction and repairs to the International Space Station.

One of the original Canadarms was converted into an orbiter boom sensor system, a 50-foot extension for shuttle arms built to inspection orbiter heat shields as part of safety procedures implemented after the loss of Columbia in 2003. The boom remains on the space station today, in the wake of the shuttle's retirement.

Three first-generation Canadarms remain. NASA kept one for engineering analysis and "potential future use," according to NASA spokesman Michael Curie.

A second arm is being refurbished at MDA before being shipped for display at the Canadian Space Agency headquarters near Montreal.

The third is on display at the National Air and Space Museum's airport annex, the Stephen F. Udvar-Hazy Center, near space shuttle Discovery. The arm and spacecraft arrived at the museum at the same time arrived at the same time in April 2012.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus