10 geological discoveries that absolutely rocked 2020

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This year, scientists uncovered some of the Earth's most well-kept secrets. They found hidden rivers, chunks of lost continents and remnants of ancient rainforests, and they delved into the planet's ancient history using cutting-edge technologies. Who knows what they'll unearth next! While we wait to find out, here are 10 of the geological discoveries that rocked our world in 2020.

Historic supereruption at Yellowstone

The Yellowstone hotspot lurks beneath the national park's geysers and hot springs, and about 9 million years ago, the volcano exploded in two historic supereruptions, scientists found. After analyzing ancient volcanic rock tracts and volcanic deposits in the region, the team uncovered evidence of two previously unknown eruptions, which they named the McMullen Creek supereruption and the Grey's Landing supereruption. The Grey's Landing eruption shattered records as the largest eruption of the Yellowstone hotspot ever detected; about 8.72 million years ago, the eruption covered roughly 8,900 square miles (23,000 square kilometers) of what is now southern Idaho and northern Nevada with volcanic debris.

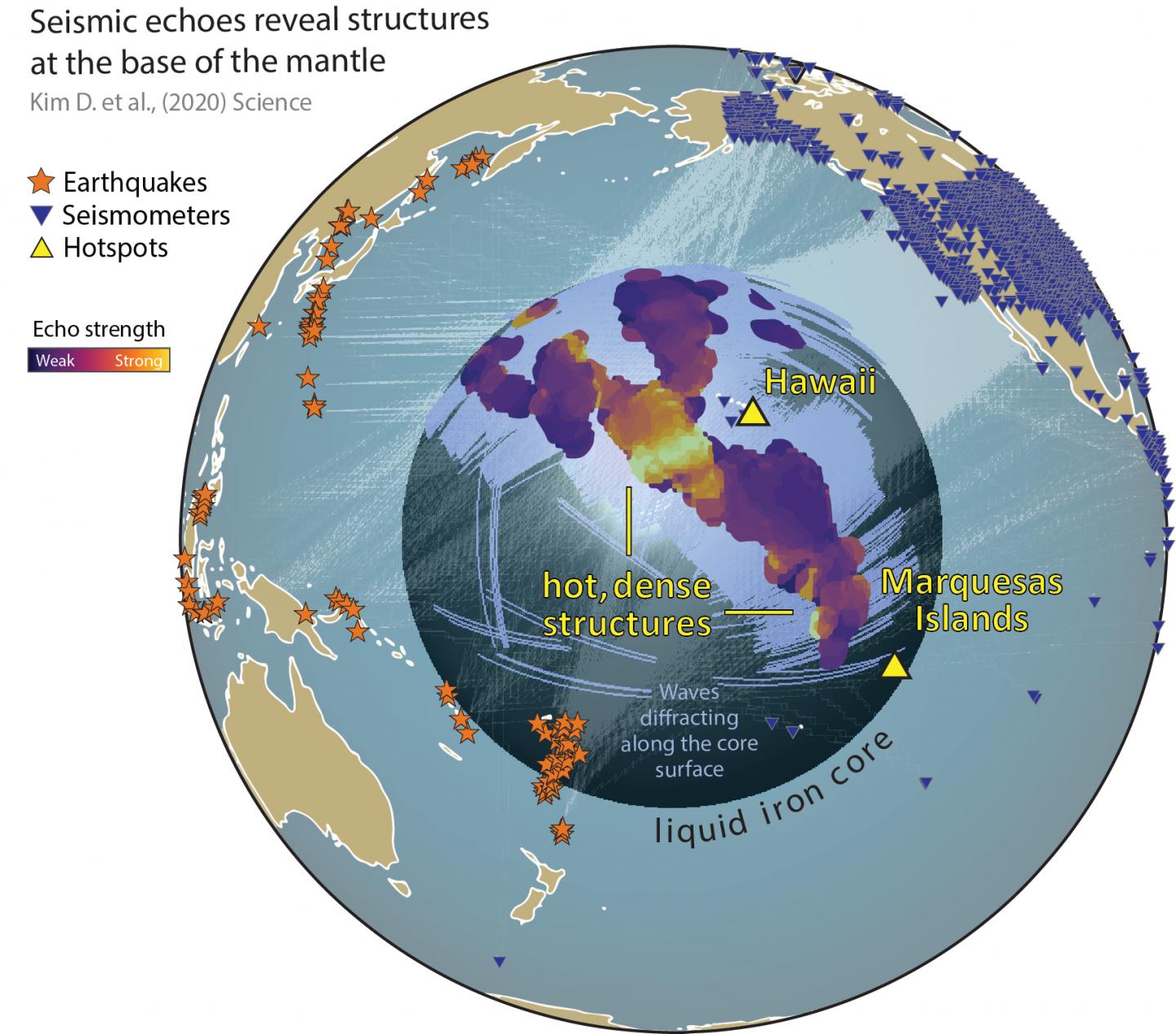

Monstrous blobs near Earth's core are bigger than we thought

Continent-size blobs of rock sit at the boundary of Earth's solid mantle and liquid outer core, and now, scientists think they might be bigger than we ever imagined. By previous estimates, the two largest blobs would measure 100 times taller than Mount Everest if pulled to the planet's surface. But after studying decades of seismic data from earthquakes, scientists now estimate that the big blob beneath the Pacific Ocean may actually be far more monstrous. For instance, one newfound structure along the edge of the blob measured more than 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) across.

Lost islands in the North Sea withstood massive tsunami

Roughly 8,000 years ago, a tsunami struck a plain between Great Britain and the Netherlands, submerging most of the region. But research suggests that some islands may have withstood the tsunami, providing a home to Stone Age humans for thousands of years. Though they remained above water for some time after the tsunami, rising sea levels eventually submerged the islands about 1,000 years later. Scientists learned the lost islands had survived the tsunami only after collecting sediment from the seafloor near the eastern English estuary of the River Ouse.

Related: Changing Earth: 7 ideas to geoengineer our planet

Earth's core is a billion years old

The Earth's solid inner core — a 1,500-mile-wide (2,442 kms) ball of iron — likely formed about 1 billion to 1.3 billion years ago, scientists estimate. By recreating the conditions found in the core on a teeny, tiny scale, the team was able to calculate how long it would take for a blob of molten iron to build up to the core's current size. The time window of roughly 1 billion years lines up nicely with historic fluctuations in the planet's magnetic field, which grew significantly stronger between 1 billion and 1.5 billion years ago. The crystallization of the inner core may have provided this boost of magnetism, since the process would have released heat into the liquid outer core; heat drives a churning motion in the liquid that then powers the magnetic field.

Related: Earth's core is a billion years old

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Piece of a lost continent found under Canada

About 150 million years ago, a now-lost continent broke up into enormous fragments — and one big chunk was recently discovered lurking under Canada. Scientists made the discovery while studying a type of diamond-bearing volcanic rock called kimberlite, which had been collected from nearly 250 miles (400 km) beneath Baffin Island in northern Canada. The mineral chemistry of the kimberlite matched that of the long-lost continent, making the sample location the deepest point where evidence of the continent had ever been found.

Related: Piece of lost continent discovered beneath Canada

Underwater rivers found near Australia

This year, scientists discovered massive rivers of cold, salty water that flow from the Australian coast out into the deep ocean. The rivers, which researchers found using autonomous underwater vehicles, form when shallow waters near the coast lose heat during the winter. Evaporation during the summer months makes this shallow water saltier than deep water, so when it cools, the dense, salty water sinks and snakes through the ocean as an underwater river. These rivers span thousands of miles and carry nutrients, plant and animal matter and pollutants out into the ocean.

Related: Massive underwater rivers were discovered off the coast of Australia

Ancient rainforest found under Antarctic ice

Antarctica might be the last place you'd expect to find remnants of an ancient rainforest, but that's exactly what scientists found under the western side of the continent. The forest's remains were discovered in a sediment core drilled from a seabed near Pine Island Glacier. A layer of sediment within the core stood out from the rest, as its color clearly differed from those around it; upon closer inspection, scientists found ancient pollen, spores, bits of flowering plants and a network of roots within the layer. The sample dated back 90 million years, to the mid-Cretaceous period, when the now-frozen Antarctic had a much milder climate.

Related: Remains of 90 million-year-old rainforest discovered under Antarctic ice

Ancient seabed buried 400 miles beneath China

A seabed that once lined the bottom of the Pacific Ocean was found buried hundreds of miles beneath China, where it continues to descend toward the Earth's mantle transition zone. The slab of rock once sat atop the oceanic lithosphere, the outermost layer of Earth's surface, but was pushed downward when it collided with a neighboring tectonic plate, in what's called a subduction event. Scientists had never detected a subduction event so deep beneath the planet surface, at depths ranging between 254 to 410 miles (410 to 660 km) underground.

Related: Ancient fragment of the Pacific Ocean found buried 400 miles below China

Lost tectonic plate gets resurrected?

Scientists digitally reconstructed a tectonic plate and showed that its movement likely gave rise to an arc of volcanoes in the Pacific Ocean some 60 million years ago. In the past, some geophysicists argued that the plate, known as Resurrection, never existed. But if it did exist, the plate would have been pushed beneath Earth's crust tens of millions of years ago; so using computer reconstruction, scientists reversed that motion, virtually pulling it and other ancient plates back to the surface. They found that Resurrection would have fit in like a perfect puzzle piece, just east of two plates called Kula and Farallon, and that its edge matches up with ancient volcanic belts in Washington State and Alaska.

Related: 'Lost' tectonic plate called Resurrection hidden under the Pacific

Towering coral structure dwarfs Empire State Building

The first detached coral reef discovered in more than 100 years stands taller than the Empire State Building. Measuring 1,640 feet (500 meters) high from base to tip, the tower of coral stands freely near the rest of the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia. The blade-like structure measures 1 mile (1.5 km) wide at its base and its peak sits about 130 feet (40 m) below the sea's surface.

Related: Coral 'tower' taller than the Empire State Building discovered off Australian coast

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus