Supercameras Could Capture Never-Before-Seen Detail

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A supercamera that can take gigapixel pictures — that's 1,000 megapixels — has now been unveiled.

Researchers say these supercameras could have military, commercial and civilian applications, and that handheld gigapixel cameras may one day be possible.

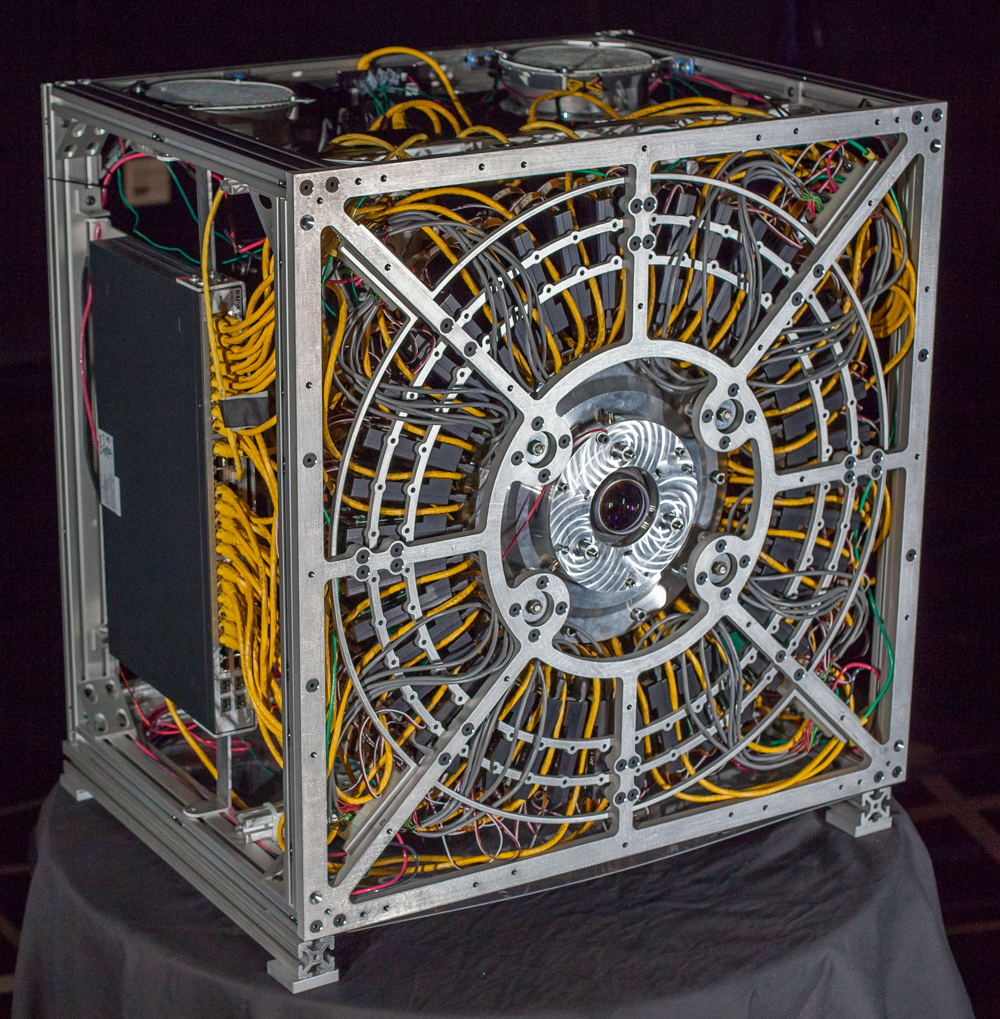

The gigapixel camera uses 98 identical microcameras in unison, each armed with its own set of optics and a 14-megapixel sensor. These microcameras, in turn, all peer through a single large spherical lens to collectively see the scene the system aims to capture. Since the optics of the microcameras are small, they are relatively easy and cheap to fabricate.

A specially designed electronic processing unit stitches together all the partial images each microcamera takes into a giant, one-gigapixel image. In comparison, film can have a resolution of about 25 to 800 megapixels, depending on the kind of film used.

"In the near-term, gigapixel cameras will be used for wide-area security, large-scale event capture — for example, sport events and concerts — and wide-area multiple-user scene surveillance — for example, wildlife refuges, natural wonders, tourist attractions," said researcher David Brady, an imaging researcher at Duke University in Durham, N.C., told InnovationNewsDaily. "As an example, a gigapixel camera mounted over the Grand Canyon or Times Square will enable arbitrarily large numbers of users to simultaneously log on and explore the scene via telepresence with much greater resolution than they could if they were physically present."

['Dream' Space Telescope for Military Could Spy Anywhere on Earth]

Gigapixel cameras may have scientific value. For instance, a gigapixel snapshot of the Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge allowed details such as the number of tundra swans on the lake or in the distant sky at that precise moment to be seen, allowing researchers to track individual birds and analyze behavior across the flock. Very wide-field surveillance of the sky is possible as well, enabling analysis of events such as meteor showers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I believe that the need to store, manage and mine these data streams will be the definitive application of supercomputers," Brady said.

The gigapixel device currently delivers one-gigapixel images at a speed of about three frames per minute. It actually captures images in less than a tenth of a second — it just takes 18 seconds to transfer the full image from the microcamera array to the camera's memory.

The camera also currently only takes black-and-white images, since color pictures are more difficult to analyze. "Next-generation systems will be color cameras," Brady said.

In addition, the camera is quite large, measuring 29.5 by 29.5 by 19.6 inches (75 by 75 by 50 centimeters), a size required by the space currently needed to cool its electronics and keep them from overheating. The researchers hope that as more efficient and compact electronics get developed, handheld gigapixel cameras might one day emerge, similar in size to current handheld single-lens reflex (SLR) cameras.

[Shapeshifting Mobile Camera Lens Inspired by Human Eye]

"Of course, it is not possible for a person to hold a camera steady enough to capture the full resolution of a gigapixel camera, so it may be desirable to mount the camera on a tripod," Brady said. "On the other hand, motion compensation strategies may overcome this challenge."

The researchers are also working on more powerful cameras. They have currently built a two-gigapixel prototype camera that possesses 226 microcameras, and are in the manufacturing phase for a 10-gigapixel system. Ten- to 100-gigapixel cameras "will remain more backpack-size rather than handheld," Brady said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the June 21 issue of the journal Nature.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus