Earthquakes Off Alaska Pose US Tsunami Risk

The risk of a deadly tsunami ravaging the United States is now leading scientists to investigate hazards posed by giant earthquakes off the Alaskan coast.

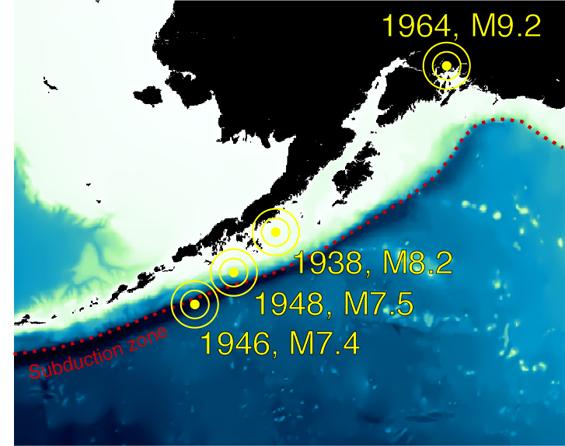

Scientists are concentrating on the Alaskan-Aleutian subduction zone, where the tectonic plate underlying the Pacific Ocean is diving underneath the continental plate underlying North America. Tsunamis can be caused by earthquakes, especially large ones, and the second-largest recorded earthquake in history was a magnitude 9.2 at this zone in 1964.

"It concerns us a lot that we might have deadly waves aimed at U.S. shores," said geophysicist David Scholl, an emeritus scientist at the U.S. Geological Survey at Menlo Park, Calif., who discussed the work in Eos, a publication from the American Geophysical Union.

Traveling tsunamis

The fear is that a tsunami caused by a major earthquake along this zone could race across the Pacific Ocean and devastate highly populated areas of the U.S. West Coast, as well as Hawaii.

"We've been focusing on tsunami risks since 2004, when the Banda-Aceh earthquake and tsunami led to a loss of about 250,000 lives, and then the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake and tsunami claimed another 20,000 or so people and caused a nuclear disaster," Scholl told OurAmazingPlanet. "Tsunamis show us that you may have an earthquake in one part of the world that visits damage on areas thousands of miles away."

For instance, a tsunami in 1946 generated by a magnitude 8.6 temblor on the Alaskan-Aleutian subduction zone near Unimak Pass, Alaska, caused significant damage along the West Coast, claimed 150 lives in Hawaii, and inundated shorelines as far away as the South Pacific islands and Antarctica.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"These waves can travel at 500 mph [700 kph]," Scholl said. "From the Aleutians, a tsunami could get to Hawaii in four or five hours, two or three hours to get to Washington, Oregon, British Columbia and the California coast. And they don't lose much energy as they go. The waves aren't horribly high as they travel over the deep ocean, only a meter [3 feet] or so, but when they get to the coast, in shallow waters they grow in height to dozens of meters, and in places like Long Beach harbor in California, they'd cause rapid currents that can tear up the harbor area."

Next big one

It remains uncertain where the next tsunami generated along this zone might occur. It appears unlikely that a quake as large as the magnitude 9.2 event in 1964 will happen again soon — the interval for such major quakes is about 900 years. However, the areas between the Shumagin and Fox Islands on the zone may cause trouble, Scholl said. In addition, the last time the Semidi Islands section of the zone experienced a great earthquake was in 1938, a magnitude 8.2 event, and enough time has passed for strain to build up for another major temblor. Indeed, satellite analysis of the area suggests the shallower portion of this section is accumulating strain at a high rate.

Research is under way to examine the ancient history of tsunamis on several of the Aleutian Islands by looking at layers of sediment there. The hope is to yield insights on how often tsunamis recur there and to link these deadly waves to specific earthquakes to better model the potential deadliness of tsunamis based on the magnitudes and locations of the earthquakes that cause them. Such research is key to building effective defenses against tsunamis. [History's Biggest Tsunamis]

"When it came to the Fukushima disaster in Japan, they designed a sea wall to handle a tsunami, but they ended up lowballing how high the wave would be," Scholl said. "You have to know how bad tsunamis have been to know what to prepare for."

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.