Weekend Lyrid Meteor Shower Visible From Earth, Space and ... Balloon?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The annual Lyrid meteor shower will hit its peak this weekend and promises to put on an eye-catching display. So much so, NASA is pulling out all the stops.

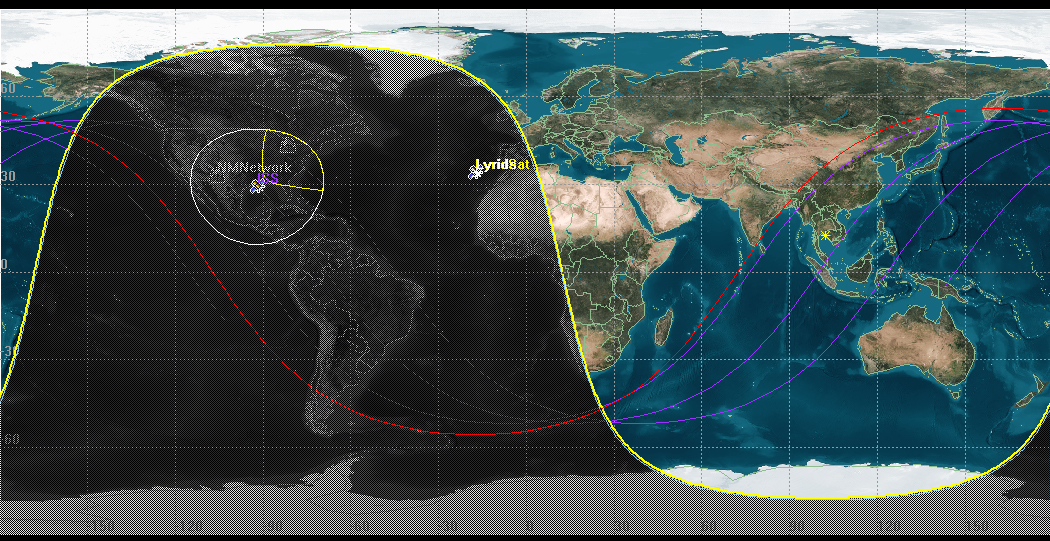

NASA scientists plan to track the Lyrid meteor shower using a network of all-sky cameras on Earth, as well as from a student-launched balloon in California. Meanwhile, an astronaut on the International Space Station will attempt to photograph the meteors from space.

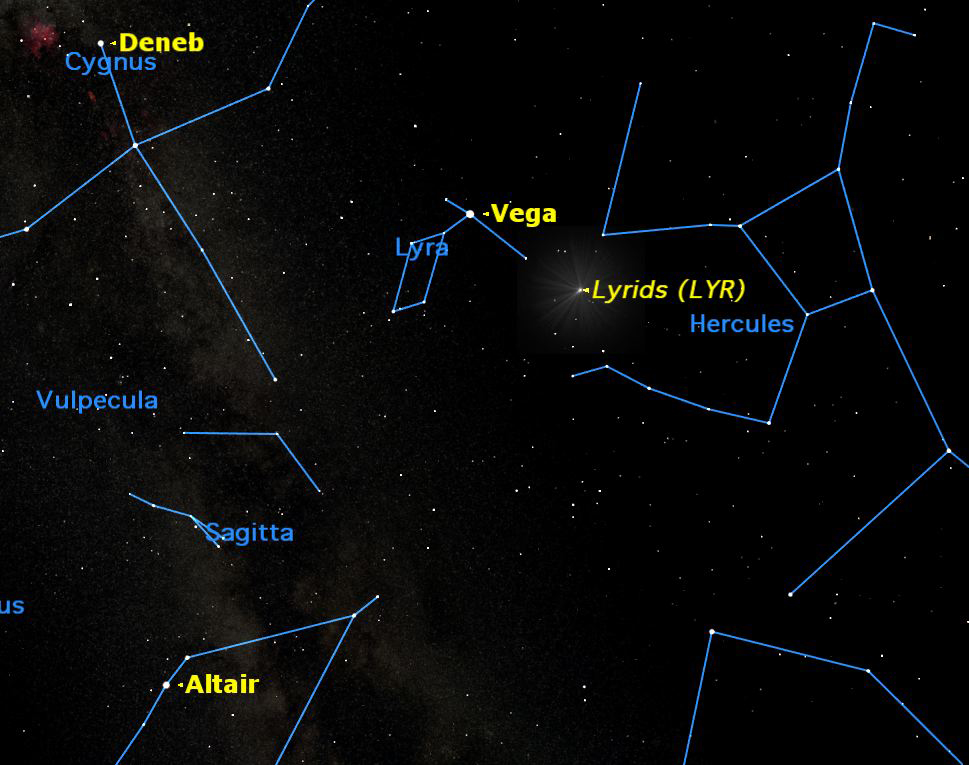

All of the work is timed for the peak of the Lyrids display of "shooting stars," which occurs late tomorrow night and early Sunday (April 21 and 22). The meteors will appear to emanate from the constellation Lyra, which will appear in the northeastern sky at midnight local time, between the two days. The best time to see them is in the hours before dawn.

"I'm eager to see if we can get observations on the ground that we can correlate with the space station, then see what this balloon payload will get for us," NASA meteor shower expert Bill Cooke told SPACE.com. "It's kind of an exciting time for us, and it's not even a major meteor shower." [Gallery: Sky Maps for 2012 Lyrid Meteor Shower]

Cooke heads NASA's Meteoroid Environment Office at the agency's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. He expects the Lyrids to offer skywatchers between 15 and 20 meteors per hour for observers under the best viewing conditions (clear weather and far from city lights). Dark skies are vital to get the best view of all meteor showers.

Promising Lyrid display

The Lyrid meteor shower is typically a faint celestial light show, but what makes this year's display special is the fact that the moon will be in its "new" phase, meaning the side facing Earth won't be illuminated and interfere with the Lyrids.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The moon messes a lot of stuff," Cooke said. "I like the moon … but it can keep us from getting work done."

And Cooke is hoping for a good showing from the 2012 Lyrid meteor shower, which is the second notable meteor display of the year. It follows the Quadrantid meteor shower in early January and kicks off what Cooke calls "meteor shower season," since the year's nighttime fireworks displays will only pick up from here.

"So this is kind of the return of the nighttime meteor shower for the year," Cooke said. "Meteor showers are returning to us."

Lyrids from space and balloon

By coincidence, the International Space Station will be flying on a path that will give its six-man crew prime seats to the Lyrid meteor shower this weekend. To take advantage of the cosmic line-up, one crew member — NASA astronaut Don Pettit — will attempt to snap photos of the Lyrids from space.

Pettit is already an accomplished space photographer and Cooke hopes that, by tracking the time of any meteors the astronaut sees, they can be matched to meteors seen from ground cameras.

"This is the first time we've tried to organize a ground campaign to look for meteors at the same time an astronaut in space is looking for meteors," Cooke said.

Then there's the research balloon.

NASA is working with astronomer Tony Phillips, who runs the skywatching website Spaceweather.com, and is leading a group of high school and middle school students in Bishop, Calif., in a project to launch a helium weather balloon into the stratosphere to try and photograph Lyrid meteors. Phillips also works with the Science@NASA website.

The weather balloon will carry a low-cost meteor camera, an experimental NASA design making its first test flight, Cooke said.

"We're going to see if we can see Lyrids from 100,000 feet," Cooke added.

How you can watch the Lyrids

Humans have been observing the Lyrid meteor shower for more than 2,600 years, NASA scientists said. The display is created when Earth passes through a stream of dust and debris left over from comet Thatcher (C/1861 G1), which follows a 415-year orbit around the sun. [Video: Comet Thatcher's Lyrid Meteors]

The meteors from comet Thatcher occur when comet dust slams into Earth's atmosphere at up to 110,000 mph (177,027 kph), igniting brilliant light displays.

While the Lyrid meteor shower appears to radiate outward from the constellation Lyra (hence its name), looking straight at the constellation isn't a good idea.

"The last thing you want to do is look at Lyra, which is the direction of the radiant, because the meteors in that direction have very short tails and will appear as a dot to you," Cooke advised. "The best thing to do with any meteor shower is to go out there, lie on your back and look straight up."

Don't expect to see a sky filled with shooting stars, either, Cooke warned. A few meteors per hour is what the average skywatcher should expect, he said.

Lyrid meteor skywatchers with good weather should venture outside in the late-night hours Saturday or early Sunday, preferably after midnight to catch the sky show around its peak, which occurs at 1:30 a.m. EDT (0530 GMT). You should allow up to 40 minutes for your eyes to adjust to the darkness.

A reclining folding chair, blanket and good company can help enhance your Lyrid observing experience too.

Cooke will also host a "NASA Up All Night" webchat to discuss the Lyrids in real-time, offering a chance for those with rainy skies to see the meteor shower remotely. You can join the Lyrid meteor shower webchat tomorrow between 11 p.m. and 5 a.m. EDT (0300 and 0900 GMT) here: http://www.nasa.gov/connect/chat/lyrids2012_chat.html

A live video feed from NASA's all-sky camera network is available here: http://www.nasa.gov/connect/chat/allsky.html

And if you don't see many Lyrid meteors in the night sky, don't be discouraged. There are plenty other amazing skywatching sights in April's evening sky.

"You have Venus over in the west blazing brilliantly, and then we have Mars over in the East, and then Saturn. If you stay up late, at sunrise there's Mercury, but it tends to be really hard for people to spot," Cooke said. "If the weather is favorable, it certainly wouldn't be a bad night to do a little stargazing."

If you snap an amazing photo of the Lyrid meteor shower or other skywatching target and you'd like to share it for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com Managing Editor Tariq Malik on Twitter @tariqjmalik. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcomand on Facebook.

Tariq is the editor-in-chief of Live Science's sister site Space.com. He joined the team in 2001 as a staff writer, and later editor, focusing on human spaceflight, exploration and space science. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times, covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus