Sex Done, Female Fish Stop Paying Attention

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Love may be blind, and once its over, it can be deaf, too. At least that's the case for certain female fish that appear to hear better when they are ready to reproduce. The enhancement is tied to an increase in the fish-equivalent of estrogen.

A similar correlation may be at play in humans.

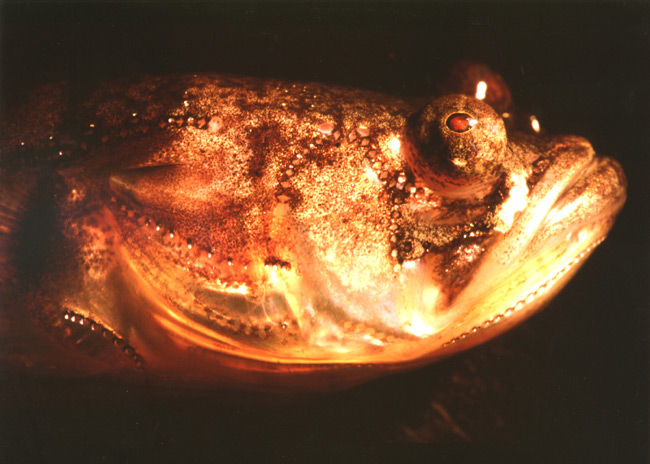

The plainfin midshipman fish is known to biologists and sailors along the U.S. West Coast for the love song the male belts out when he has a nest ready for a female's eggs.

This fertility advertisement "sounds like a drone of bees or perhaps the mantra sung by those doing yoga," Andrew H. Bass from Cornell University told LiveScience.

During the late spring and summer, sailors often hear the combined chorus of the midshipman males, but research had found that females who had already laid their eggs no longer seemed to respond to the distant hum.

To determine the cause of this selective hearing, Bass and his team took female midshipman without eggs and injected them with an estrogen-like hormone that is normally elevated in egg-carrying females. They measured the electrical activity in the nerve coming from the fish's inner ear and found that the fish became sensitive to frequencies above 100 Hz only when the hormone level was increased.

This shift in spectrum-response helps the reproductive females hear the upper harmonics of the mating call, the scientists speculate, which travel further in the shallow waters where the midshipman mate.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hormone-dependent hearing could be operating in human females. In detailing their study in the journal Science, the researchers cite other work that which has identified variations in auditory sensitivity of women corresponding to the menstrual cycle.

Furthermore, women have estrogen receptors in their ears, similar to the hormone receptors that Bass and his colleagues found in the midshipman females.

"The significance of these receptors in the human ear are unknown - our work is the first to show the possible significance of these receptors for hearing," Bass said.

If estrogen does turn up the volume, perhaps this explains why some men don't hear their wives.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus