Prehistoric Landslide Created Hidden Lake

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A catastrophic prehistoric landslide left behind a giant lake along what is now a river in California, researchers have discovered. The landslide also apparently left its mark on the river's trout, in the form of a genetic similarity, the researchers added.

Scientists investigated Northern California's Eel River to study large, slow-moving landslides. The river stretches about 200 miles (320 kilometers) in length and carries extraordinarily large amounts of sediment down its course, the most of any river not fed by a glacier in the contiguous United States.

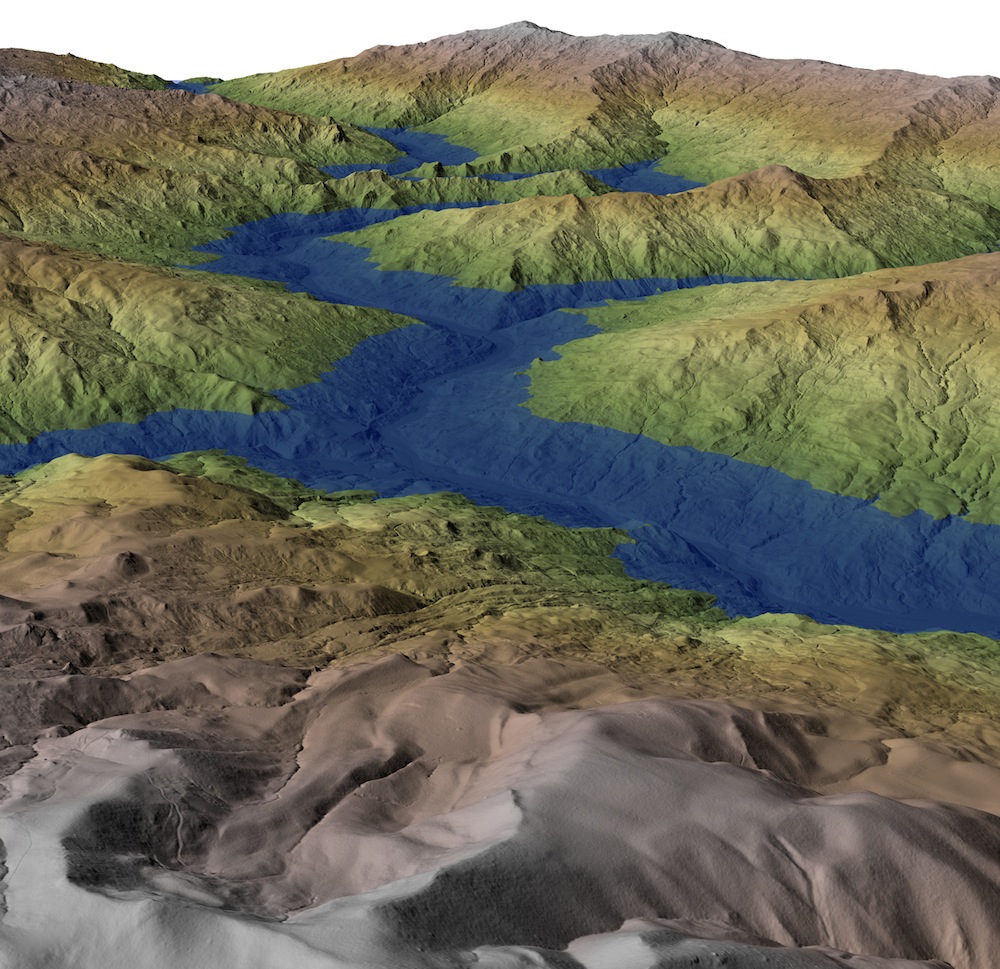

The researchers analyzed the landscape using a laser range-finding system mounted on an aircraft and hand-held GPS units. They discovered that along a stretch of the river, terraces on adjacent slopes stayed oddly similar in elevation, rather than decreasing downstream as expected.

"This was the first sign of something unusual, and it clued us into the possibility of an ancient lake," said researcher Benjamin Mackey, a geomorphologist at the California Institute of Technology. The stretch they detected most likely represented where a lake with relatively stable shores once was, explaining why the leftover terraces were all of similar elevation.

Evidence of a disaster

Altogether, the researchers found evidence of a giant landslide that dammed the upper reaches of the Eel River with a wall of loose rock and debris 400 feet (120 meters) high about 60 miles (100 km) southeast of Eureka, Calif. The result was a lake about 30 miles (50 km) long. [10 Longest Rivers]

"The presence of a dam of this size was highly unexpected in the Eel River environment given the abundance of easily eroded sandstone and mudstone, which are generally not considered strong enough to form long-lived dams," Mackey said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mackey and his colleagues studied isotopes of carbon to date the sediments within this former lake. The isotope carbon-14 is unstable and decays over time, so analyzing the ratio of carbon-14 to other carbon isotopes can shed light on how much time has passed. Results suggest the landslide occurred 22,500 years ago.

These findings match details from other studies that showed a dramatic drop in the amount of sediment deposited from the river just offshore in the ocean at approximately the same time. The landslide probably came from Nefus Peak, which bears a massive landslide scar on its southwestern flank.

"The damming of the river was a dramatic, punctuated affair that greatly altered the landscape," said researcher Joshua Roering at the University of Oregon.

Eventually, the dam was breached, which would have generated a huge flood. Landslide activity and erosion have since erased much of the evidence for the now-gone lake.

Landslide fish

This catastrophic event might explain the genetics of steelhead trout in the Eel River. Past research found a striking relationship between summer-run and winter-run steelhead trout in the river — a genetic similarity not seen among these types in other nearby rivers. The two kinds of fish are usually geographically isolated and don't normally interbreed. The scientists suggest both types of ocean-going trout mingled when the dam blocked their normal migration routes. "This period of gene flow between the two types of steelhead can explain the genetic similarity observed today," Mackey said.

Once the dam burst, the fish would have reoccupied their preferred spawning grounds and resumed different genetic trajectories, Mackey added.

"Although current physical evidence for the landslide dam and paleo-lake is subtle, its effects are recorded in the Pacific Ocean and persist in the genetic makeup of today's Eel River steelhead," Roering said. "It's rare for scientists to be able to connect the dots between such diverse and widely felt phenomena."

This region is not typically considered vulnerable to such large landslide dams, Mackey added. These findings "should encourage reassessment of landslide hazard in landscapes similar to the Eel River area," Mackey told LiveScience.

Mackey, Roering and their colleague Michael Lamb detailed their findings online today (Nov. 14) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus