Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Skywatchers on terra firma probably won't see much when the Draconid meteor shower peaks this Saturday (Oct. 8), but a balloon launched by a group of California schoolkids could get a bird's-eye view.

While the Draconid meteor shower should be particularly active this year, the main fireworks display will likely be drowned out by sunlight in the Western Hemisphere and a bright moon in the East, experts say. The camera-toting student balloon, however, should be high up in the stratosphere, poised to snap some shots of meteors blazing by.

"When you're up that high, it's really dark," said team member Anna Herbst, a sophomore at Bishop Union High School in Bishop, Calif. "So hopefully we'll be able to see the meteors from up there. And we'll be filming the whole time." [Photos: The Perseid Meteor Shower of 2011]

A student balloon experiment

Herbst is one of 15 high school and middle school students participating in the balloon mission. All of the members of the team, which is called Earth to Sky, are from Bishop, a town of about 4,000 people in central California near the Nevada border.

Earth to Sky aims to send its unmanned balloon up to the stratosphere on Saturday (Oct. 8), and have it ready and waiting for the peak of the Draconid shower. That's predicted to happen between 3 p.m. and 5 p.m. EDT (1900 and 2100 GMT), when around 750 meteors per hour could streak through the sky, NASA officials said.

The helium balloon will be carrying two GPS systems, a cryogenic temperature logger and four cameras. Three of the cameras will be off-the-shelf models that were sensitive enough to spot Venus on a previous flight, and one will be a special low-light meteor camera provided by NASA, the students said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"With the low-light camera, we're even more likely to see [the shower], because our [other] cameras aren't specially designed for the dark environments of the stratosphere," said Michael White, also a sophomore at Bishop Union.

While this will be the group's first dedicated astronomy mission, the team already has extensive experience with balloon experiments, having already launched five since May 2011.

"Each one has gone higher than the one before," said the group's leader and adviser, astronomer Tony Phillips of Science@NASA. "Our last flight got up to about 100,000 feet, and we're actually hoping with this flight to get up to about 120,000 feet."

Eventually, the balloon will pop, and its payload will float back down to Earth via parachute. The team will recover the cameras and see if they got any good shots.

Spotting the Draconids

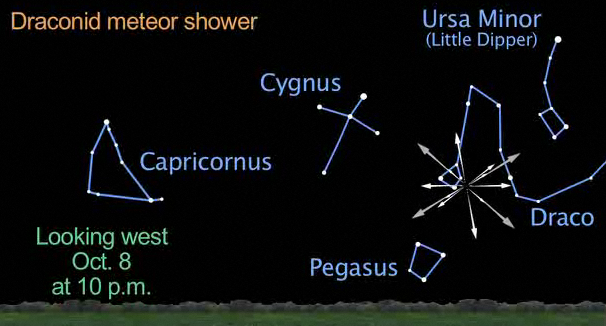

Like other meteor showers, the Draconids — so named because they appear to radiate from the constellation Draco — result when Earth plows through streams of debris shed by a comet on its path around the sun.

In the Draconids' case, this parent comet is called Giacobini-Zinner, so the Draconid shower is also known as the Giacobinids. [Best Comet Close Encounters]

Most years, the Draconids are weak and faint, with peak meteor rates of about 10 per hour. That's barely above the normal "background" rate of shooting stars. This year, however, Earth will collide especially squarely with some debris trails, and the Draconids will get a jolt.

But, most backyard skywatchers probably won't get to fully appreciate the super-charged meteor shower. The peak will likely be obliterated by the sun in North America and washed out by a moon that's 90 percent full in parts of the world where night has already descended.

So the students' balloon could get some of the best pictures of the shower this year, experts said.

"I hope they catch some Draconid fireballs for us to analyze," said Bill Cooke, head of NASA's Meteoroid Environment Office at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., in a statement. "They could be the only ones we get."

Scientists like Cooke are keen to get more data on the Draconids, Phillips said, because they aren't exactly sure where all of comet Giacobini-Zinner's various debris streams are.

"They want to use any data they can to pinpoint the location of these dust streams, so they can know if we're going to hit them again in the future," Phillips told SPACE.com.

More missions coming

While Earth to Sky is hoping to get some good images of Draconid shooting stars, this mission is also something of a practice run for the group. They plan to launch another mission to observe next month's Leonid meteor shower, which tends to put on a more dramatic show.

"Although I'm not pessimistic for the Draconids, I think our odds are better for the Leonids, because we will have tested our system by then," Phillips said. "And the Leonids are just a brighter meteor shower."

The team is also working toward an even more ambitious goal. Next year, they hope to launch some science payloads toEarth orbit aboard a small satellite, Phillips said.

The students are doing all of this on their own time, outside school hours and during lunch. The work is not part of a structured class.

"The reason we do it is because we're interested in learning about space and such, and weather balloons," said Bishop Union sophomore Wyatt Walsh. "We don't get credit for it. We just do it for fun."

Editor's note: If you snap amazing Draconid meteor photos you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus