Giant Space 'Blob' Glows Green From Galaxies Within

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

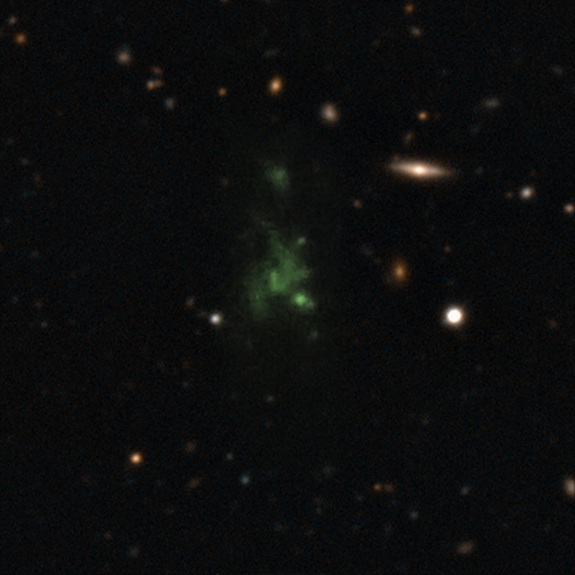

A giant, glowing blob of gas – a cosmic relic of the early universe – is lit by galaxies within it, according to a new study.

"We have shown for the first time that the glow of this enigmatic object is scattered light from brilliant galaxies hidden within, rather than the gas throughout the cloud itself shining," lead author Matthew Hayes, of the University of Toulouse in France, said about the Lyman-alpha blob, a rare and brightly lit gas cloud structure that is among the largest known objects.

A team of astronomers used the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT), located at the Paranal Observatory in Chile, to study the Lyman-alpha blob. These huge structures of hydrogen gas are usually seen in regions of the early universe where matter is concentrated.

The astronomers found that the light coming from the blob was strangely polarized, and by studying this effect they were able to unlock the mystery of how the blob shines. [See photo of the mysterious green space "blob"]

The findings of the new study are published in the Aug. 18, 2011 issue of the journal Nature.

Studying how light is polarized allows astronomers to discern how the light is produced. If light is reflected or scattered, it becomes polarized, and this subtle effect can be detected using very sensitive ground-based instruments. However, measuring the polarization of light from a Lyman-alpha blob is tricky, the researchers said, because the target is so far away.

The astronomers used the VLT to study the blob for 15 hours, and they found that the light was polarized in a ring around the central region but that there was no polarization at the center.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This effect is almost impossible if light simply comes from the gas falling into the blob due to gravity, the researchers said. Instead, it would be expected if the light originated from galaxies embedded in the blob's central region before becoming scattered by the gas. [6 Weird Facts About Gravity]

Lyman-alpha blobs can measure a few times larger than the Milky Way, and are as powerful as the brightest galaxies.

The blobs are typically seen from vast distances, so they appear as they were when the universe was only a few billion years old. As a result, they are important for understanding how galaxies formed and evolved when the universe was much younger.

Hayes and his team studied one of the first, largest and brightest known Lyman-alpha blobs – LAB-1, which was discovered in 2000 and is so far away that its light takes about 11.5 billion years to reach Earth.

LAB-1 measures about 300,000 light-years across. Embedded within it are several primordial galaxies, including one active galaxy.

The researchers said more of these blobs need to be examined to see whether the results obtained for LAB-1 are also true for them.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience.com. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus