Record Heat Unlikely to Cool Climate Change Debate

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

If this summer's record-breaking heat has you gulping iced tea while bemoaning the evils of climate change, you're probably not alone. But climate communications experts suggest that any extra interest in global warming triggered by the heat wave will be gone by the first winter snow.

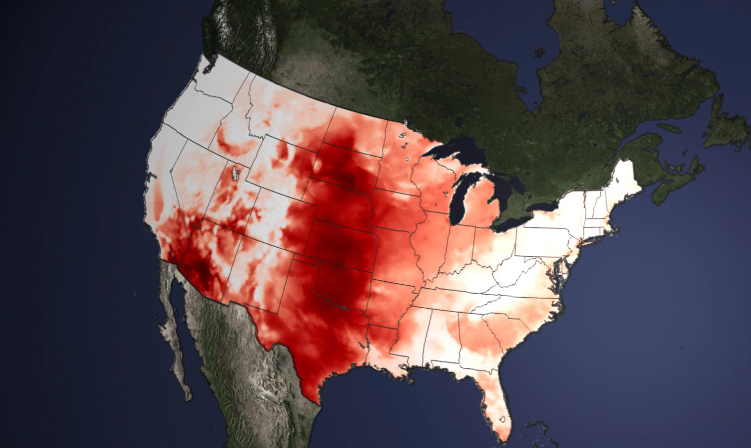

July brought oppressive heat to much of the country, with all 50 states setting high temperature records. Climate scientists say that such heat waves will be the norm in the future if climate change continues unabated, but experts say it will take more summers as hot as this one to shift the climate change policy debate.

"It's record-setting temperatures, and people are thinking, 'This is global warming, maybe we should think about this,'" said Ye Li, a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Decision Sciences at Columbia Business School, who has studied the influence of temperature on climate-change beliefs. "But will it have a long-term impact? Part of that depends on whether people remember these temperatures. I know every winter I'm not remembering what the hottest days of summer were like."

Weather versus climate

No one weather event, including this heat wave, can be attributed directly to climate change, since climate is the sum of weather over time. Rather, climate change loads the dice, making it more likely that with any roll, you'll come up with extreme weather, including heat waves and heavy precipitation.

This tendency toward weather extremes is why a warming planet can expect more heat waves in summer, and at the same time, heavy snowfalls in winter.

Heating up: public opinion

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The inability to directly pin a single weather event on climate change makes it tough for scientists to communicate the realities of climate change, Li told LiveScience. Public opinion is split on global warming, a split that tends to fall along party lines.

The Democrat-Republican divide has been growing in recent years. A 2008 Gallup analysis found that in 1998, just under half of both Democrats and Republicans said the effects of global warming had already begun. In 2008, 76 percent of Democrats agreed with that statement, while only 41 percent of Republicans did.

Media and social networks also influence people's opinions, said Anthony Leiserowitz, the director of the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication. News coverage is how most people learn about climate, Leiserowitz told LiveScience, so quantity and quality of coverage matters. Similarly, people's friends, family and colleagues may influence their beliefs.

But perhaps one of the most unexpected factors that influences people's opinions on climate change is what the weather looks like outside. Columbia's Li surveyed Americans and Australians and found that when it's hotter outside, people are more likely to be worried about global warming. When it's cooler, that worry dissipates.

"This temperature effect is actually quite large," Li said. "It's possible that if you give people enough hot days, it might even overcome a staunch Republican's belief against climate change."

Cherry-picked data

On the other hand, people tend to cherry-pick information based on their pre-existing beliefs about climate, Leiserowitz said. In May 2011, he and his colleagues released a report on people's assessments of global warming. They included questions about whether the winter's snowstorms and the previous summer's record-heat influenced people's beliefs about warming.

People who don't hold strong opinions about global warming tended to be swayed by the weather, Leiserowitz said. Snow made them doubt warming, while heat prompted them to accept it.

But the people at the extremes — the ones whose minds were made up either way — only gave credence to the weather event that fit their preferred narrative. About 77 percent of people who were dismissive of climate change said heat waves did not make them consider the idea that global warming might be real. Likewise, 53 percent of people who are highly alarmed about global warming said snowstorms did not soothe their minds.

Bigger snowstorms are an effect of global warming, and some of the alarmed group may have known this, Leiserowitz said. However, he said, other studies show that a significant portion of this group do not understand that climate change can result in more snow, so an informed population cannot explain the entire effect. [Top 10 Surprising Results of Global Warming]

Getting the word out

Misinformation about climate change is rampant, said Edward Maibach, the director of the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University in Virginia. Almost 6 out of 10 Americans don't know that the percent of climate scientists who are convinced that the climate is changing is in the high 90s, Maibach told LiveScience.

The myth that there is scientific disagreement on the topic "turns out to be a very important determinative factor in undermining people's belief that the climate is changing," Maibach said.

Exacerbating the issue is the fact that besides environmental groups, there is little public education on climate change, Maibach said. Unfortunately, he said, environmental groups are viewed with skepticism and not trusted.

This summer's temperatures are unlikely to change the equation, Maibach said.

"I don't think it's going to shift public opinion dramatically," he said.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus