Tiny Creatures Rediscover the Joy of Sex

Tiny spider relatives have rediscovered the joy of sex, regaining the ability to mate after their arachnid ancestors lost it, marking a reproductive first in the annals of animal evolution.

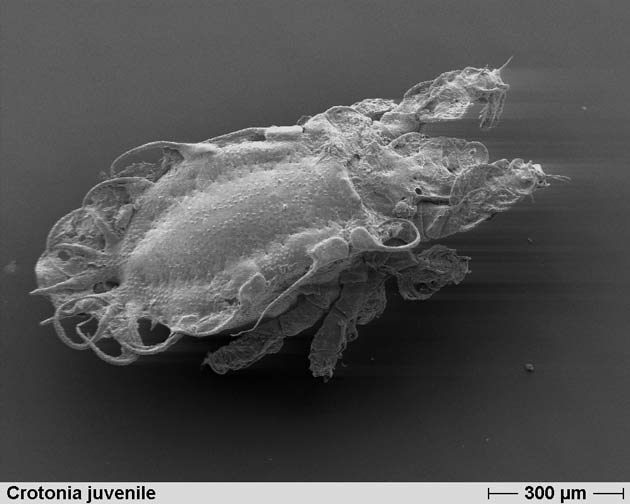

There are 45 known species of these spider relatives, mites known as Crotoniidae, which are roughly the size of a pin head, at 1.5 millimeters across.

The Crotoniidae reproduce by having sex, which wouldn't be too strange except that they are very similar physically to Camisiidae, a family of some 80 mite species that all reproduce asexually via parthenogenesis, in which females give birth to young without having sex with males.

Evolutionary biologist Katja Domes at the Technical University of Darmstadt in Germany and her colleagues examined genetic sequences in two Crotoniidae species and a diverse range of 13 other mite species. Their calculations show the sexual Crotoniidae evolved from the asexual Camisiidae, the first known reversal to sexuality from asexuality within the animal kingdom. (The only other known such reversal is a plant, the mouseear hawkweed, or Hieracium pilosella.)

Domes and her colleagues detailed their findings online April 16 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The Crotoniidae and the Camisiidae are types of mites known as oribatids, where parthenogenesis is unusually widespread, seen in nearly one-tenth of the roughly 10,000 known oribatid species. Scientists know many parthenogenetic oribatids produce rare, sterile males, suggesting the ability to produce functional males was preserved but "dormant" in the Camisiidae and reactivated in the Crotoniidae.

When it comes to why the Crotoniidae regained sexuality, Domes noted these mites often colonize trees. Tree-dwelling oribatids are nearly all sexual, while soil-dwelling oribatids such as Camisiidae are predominantly parthenogenetic.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If plenty of resources are available over a long time to a species, as they are with soil-dwelling mites, parthenogenesis seems to be favored, Domes explained. On the other hand, an environment with fewer resources and more enemies, such as one that tree-dwellers face, "could have caused the return to sexual reproduction in the Crotoniidae and may also be an explanation for the origin of sex in the first place," she told LiveScience.

"The most important implication is that contrary to general opinion, sexual reproduction can be regained long after it is lost," evolutionary geneticist Bill Birky at the University of Arizona told LiveScience.

"This implies that the genes required for producing males can be retained, even when those genes are rarely if ever used to produce males," he said. "This could be because male production is important even though it is rare, or it could be because those genes have important functions other than male production."

- Images: Creepy Spiders

- Mating Game: The Really Wild Animal Kingdom

- Mites in Your Pillow