Placing Landmarks on the Genome Map

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Supercomputers and next-generation gene sequencers allow researchers to explore DNA and heredity.

We typically think of heredity — eye color, body type or susceptibility to a disease — as rooted in our genes. And it is. But as biologists sequence more genomes and analyze their results, they're finding that the non-coding regions of the genome outside the genes, formerly considered "junk," play an important role in our genetic make-up as well.

Since 2001, the cost of DNA sequencing a human genome has dropped from billions to tens of thousands of dollars, enabling more focused investigations of gene expression. This has greatly improved scientists' ability to understand biological systems and their relation to illness.

Many common diseases have a genetic component that predisposes one to become sick, but the connection is rarely simple. The combination of next-generation gene sequencers and high-performance computers are enabling biologists to ask novel questions about our DNA and to glean new insights about disease and heredity.

An important example involves the role of transcription factor proteins in gene regulation, which scientists are just beginning to explore. These proteins bind to landing pads on the genome and act as control dials for gene regulation — turning genes on or off, and determining the level of gene activity in a cell.

"If you're comparing normal cells to cancer cells, you want to know what happened in the cancer cell that makes it different," said Vishy Iyer, at The University of Texas at Austin. "The gene expression patterns change, and we want to know which genes are regulated up or down, and how that came about."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

About 2,000 transcription factor proteins have been identified, and some have been linked to breast and other cancers, Rett syndrome, and autoimmune diseases. However, little is known about how they work.

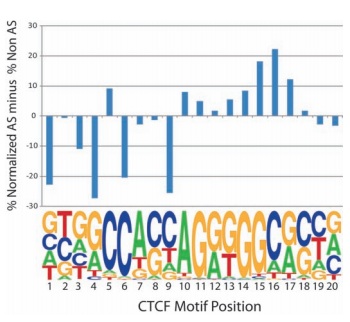

Iyer, along with colleagues at Duke, The University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and Hinxton, UK, are trying to change that. Published in the journal Science in 2010, their research was one of the first studies to use next-generation sequencing and supercomputers to explore the expression of genes related to a specific regulatory transcription factor (called CTCF). They determined that transcription factor binding is a heritable trait.

"We showed for the first time that some of the differences in DNA between individuals can affect the binding of transcription factors," said Iyer. "More importantly, that those differences could be inherited."

The group used a relatively new sequencing technology, called ChIP-Seq, to study only the regions of DNA to which the proteins of interest were bound. These base pairs were then sequenced to determine the order of nucleotides and to count how many molecules were bound to the protein.

Sounds simple enough, until you try to sequence millions of these regions to locate their exact position among the approximately three billion base pairs in the human genome.

"The genome is a vast area with many features," said Iyer. "You can think of the proteins as landmarks that we're trying to place on the genome map."

The National Science Foundation-funded Ranger supercomputer at the Texas Advanced Computing Center took the short sequence reads generated by ChIP-Seq and aligned them to the reference genome.

"It's like a text search. Though if you tried to run it in Microsoft Word, it would never finish," Iyer joked.

Using several thousand processors simultaneously on Ranger, the alignment took several hours for each of the data sets, and in total used the equivalent of 20 years on a single processor.

The single base resolution offered by next-generation sequencing enabled the researchers to look at individual, known differences in the DNA and to use those dissimilarities to examine how genes on each chromosome bind transcription factors.

"We could tell the difference in binding from the gene that you inherited from your father and mother — that was the big advance," said Iyer. "Now, we're applying this technology to cases where you know that the gene from one of your parents has a mutation that pre-disposes you to some disease."

These findings bring science one step closer to personalized medicine based on a detailed reading of an individual's genome, including the non-coding regions. Despite the tremendous complexity of the genome, Iyer is optimistic that the research will have an impact on human health.

"There are lots of diseases and for a subset, they're affecting gene expression by impacting transcription factors," he said. "If we pick the diseases and the factors smartly, I think we'll find them."

Editor's Note: This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Behind the Scenes Archive.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus