Seals Stop Shivering to Survive Extreme Dives

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

VIRGINIA BEACH, VA—While diving, hooded seals can handle oxygen levels so low they'd be lethal to humans. Now scientists are beginning to understand how they do it: The seals stop shivering and go with the chilly flow.

By switching off the shivers, which are designed to produce heat and keep a body warm, the plunging seals chill their bodies, and even their brains, to a point of hypothermia. When diving down to 3,280 feet where oxygen is scarce, the chill lowers metabolism so the animals can save on precious oxygen, explained Lars Folkow, of the University of Tromso, Norway.

The finding, presented here this week at a meeting of the American Physiological Society, could have implications for people who suffer cardiac arrest, stroke or respiratory disorders, which rob the brain of oxygen.

Icy plunge

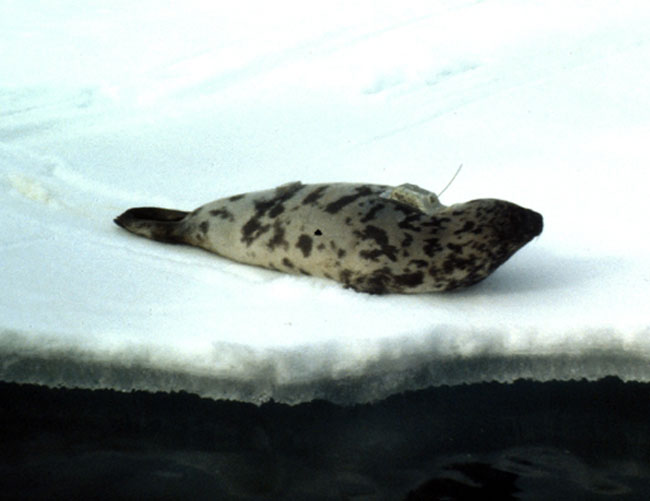

The researchers monitored seals [image] as they dove in tanks of water cooled to around 36 degrees Fahrenheit. Before, during and after the dives, the scientists measured shivering, heart rate, and brain and body temperatures of the seals.

The seals shivered while on the surface but stopped or nearly stopped shivering during dives, even though their bodies continued to cool. Upon resurfacing, the seals almost immediately started shivering again.

They also found the seals' brains cooled about 5 degrees during the dives, a chilled state that requires less energy and oxygen while reducing chances of brain damage from hypoxia.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cold proof

Seals are naturally built to survive the extreme conditions of deep dives, spending 80 to 90 percent of their time at sea underwater. They can store four times the amount of oxygen in their blood and muscles as humans, Folkow said. So by not shivering—an activity that requires oxygen for fuel— and slowing their metabolism, the animals extend the amount of time they can survive on oxygen stores.

Most of the time the stores may be sufficient, as the seals typically take many short dives. But sometimes seals in the wild can dive for so long that they use up nearly all of their oxygen.

"If our brain would receive arterial blood with that little oxygen, we would faint right away and we would probably experience brain damage, and may even die," Folkow told LiveScience.

"Somehow they tolerate hypoxia better," he said. "We don't know why."

Folkow and his colleagues speculate that the seals are equipped with more neuroglobin, a brain protein that makes oxygen available to brain tissues. This and other ideas remain to be tested, however.

- The Biggest Popular Myths

- Young Seal Strandings Puzzle Biologists

- Images: Under the Sea: Life in the Sanctuaries

- Marine Mammals Suffer Human Diseases

- Seals Dislike Cruise Ships

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus