Plumbing the Depths of Gulf Oil Spill for Coral Killers

Today (Oct. 20) marks the six-month anniversary of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, and this week the first expedition to send humans to the deep sea in areas within reach of the oil gusher is under way in the Gulf of Mexico.

Researchers are diving to the ocean floor aboard a two-person submarine to take data and samples from the massive forests of coral that thrive in the frigid, perpetual night of the deep Gulf waters.

One target is located just 40 miles (64 kilometers) from the site of the Deepwater Horizon explosion, and lies beneath the once-visible oil plume.

A group of independent scientists aboard the Arctic Sunrise, a Greenpeace vessel, sailed from Gulfport, Miss., on Oct. 14 and will explore areas as far as 3,280 feet (1,000 meters) down. Their primary tool is the cherry-red Deep Worker sub — a stubby vehicle that would look at home in a cartoon. The submarine is equipped to capture invaluable data on the deep ocean waters and the coral that lives and grows in the darkness.

Hey! Down here!

Deep-sea coral are less famous than their warm-water cousins, but far more pervasive, said mission participant Steven W. Ross, a professor at the University of North Carolina in Wilmington.

"There are more species of deep-sea coral," Ross told OurAmazingPlanet, "and they cover more area. Part of the reason is the deep sea is just bigger than the shallower water environment," said Ross, chief scientist on the expedition.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's also harder to reach, which means that although this coral is everywhere, comparatively little is known about the corals that live on the Gulf's floor.

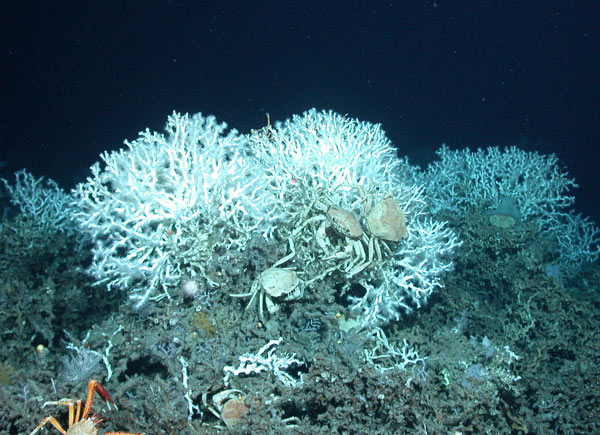

The main target of study is Lophelia pertusa, a species of cold-loving, branching coral found in almost every ocean in the world. The bone-white coral builds towering mounds in the deep ocean, and can live for hundreds, even thousands of years.

An expedition that used unmanned vehicles to take preliminary data and images of Lophelia pertusa colonies in the same area returned just weeks ago, and "we didn't see dying coral and dead fish lying on the bottom, so that's encouraging," Ross said.

"So far, there are no real obvious signs that the reefs are suffering, so we're cautiously optimistic that they've dodged a bullet," said Sandra Brooke, a coral biologist with the Marine Conservation Biology Institute who is on the ship surveying the area.

However, Ross cautioned that the lack of heart-wrenching photos of oil-blackened reefs doesn't mean the corals escaped unscathed.

Invisible killers

The damage to coral could be taking place on a less obvious level.

"One of the things that have been documented in other research is that oil can cause corals to abort their larvae," said Brooke, who specializes in coral reproduction.

This is the time of year when the coral should be spawning, and Brooke will be using the submersible to see if the waters are full of eggs and sperm, and to gather coral samples for closer study under a microscope in the lab.

"Given the timing of the reproductive cycle, they should be packed with eggs and sperm," Brooke said. "If there's nothing in there, then that's an indicator there's been some kind of impact."

Both Brooke and Ross said with little evidence of dramatic mortality, researchers are turning their focus to these less photogenic, yet possibly equally deadly effects of the oil spill. Stifled coral reproduction is just one of many possibilities.

"It may be their growth has been stunted," Brooke said. "Maybe the water column has been impacted and maybe they're starving, just like human populations after a disaster."

Brooke said that since Lophelia act as oases of life on the ocean floor, providing food and habitat to a host of creatures, damage to the coral could have far-reaching consequences.

The scientists said they plan to return to land toward the end of this week, and will have more concrete findings on the health of the coral later this year or in early 2011.

- In Images: Gulf Oil Spill — Animals at Risk

- Image Gallery: World's Cutest Sea Creatures

- Image Gallery: Creatures from the Census of Marine Life

This article was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus