Cholesterol Flap Raises Blood Pressure

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The news that the American Academy of Pediatrics is recommending cholesterol-lowering drugs for children as young as 8 years old has brought scorn against the medical establishment and the pill-popping American culture.

Newspapers and myriad websites across the globe ridiculed the AAP recommendation, announced on July 7, and questioned the connection between academia and the pharmaceutical industry. Hanna-Barbera, with perhaps cards close to chest, has been quiet about licensing Flintstone characters for chewable pills.

The recommendation does sound horrible. The only trouble is, this is not what the AAP or any doctor has recommended. Newspaper columnists and bloggers were simply reporting on what other media outlets said and not the actual report.

The AAP merely issued a set of guidelines on cholesterol in children, replacing a 1998 policy statement. These are published in the July issue of the journal Pediatrics.

In the summary of this report, in the seventh of seven statements — after practical recommendations along the lines that obese kids should get a cholesterol blood test, that high cholesterol should be treated with diet and exercise, and that if diet and exercise aren't working, a nutritional counselor should be brought in to make it work — the AAP suggests that for children with sky-high cholesterol levels or with a strong genetic disposition to high cholesterol and early death from heart disease, doctors can consider prescribing adult cholesterol medication.

Blame the parents

The AAP report comes in the midst of an emerging epidemic of childhood obesity and early-stage diabetes, cardiovascular disease and hypertension — medical conditions once seen exclusively in adults. Childhood obesity, a rarity a generation ago, is nearly entirely the result of poor diet and physical inactivity.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Many news outlets ran editorials and commentary berating parents for not taking better care of their children. There's some truth to that. But the AAP report isn't saying to give up and just take a pill.

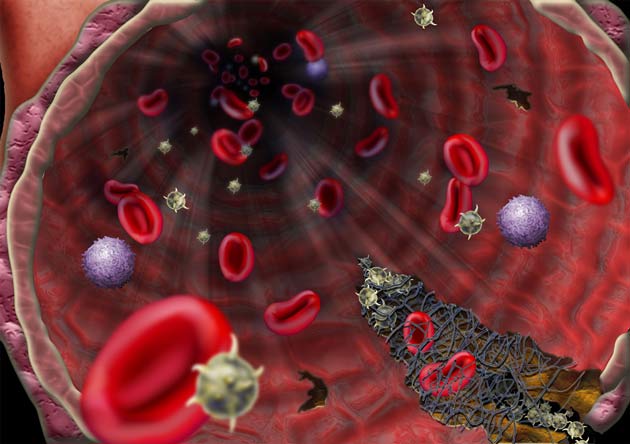

At issue are two new medical findings: People who die young of heart disease begin to develop symptoms of the disease — high blood pressure, or weakened or clogged arteries — as children, not as adults. And statins, a family of drugs that lower cholesterol, seem to be safe for adults.

The AAP knows well that upwards of 80 percent of heart attacks can be avoided by not smoking, exercising 30 minutes daily, eating well, maintaining a consistent and normal body weight, and drinking a little alcohol. These are results from the Nurses Health Study and other studies.

But there's the issue of the other 20 percent, those folks who do everything right but still die young from heart disease. Conditions such as high cholesterol in childhood likely increase their already high risk of dying young.

Report's dark side

The rage is misplaced: The AAP guidelines are a vindication of the power of diet and exercise to lower cholesterol levels. They actually place limits on pharmaceutical intervention. And pharmaceutical companies aren't expected to cash in, because a miniscule number of children would be prescribed statins; and most statins are entering the post-patent, generic-drug (i.e. little profit) stage for the big companies.

What's nuts is putting an 8-year-old on statins. Adolescence is a black box. There's absolutely no data on what these powerful drugs would do to a young body going through the hormonal upheaval of adolescence.

If the AAP report has a fault, it would be not providing enough detail as to why the age of statin use can be as low as 8 instead of, say, 15. Also, there is no discussion in the report about the cost of lengthy statin therapy or the fact that cholesterol is but one risk factor for heart disease.

Maybe more is coming, although a call for blood pressure medication for children will likely cause just as many heart attacks. And Fred Flintstone isn't much of a role model, anyway.

- The Top 10 Worst Hereditary Conditions

- The Odds of Dying

- Creature Sets Record for Living Fast, Dying Young

Christopher Wanjek is the author of the books "Bad Medicine" and "Food At Work." Got a question about Bad Medicine? Email Wanjek. If it's really bad, he just might answer it in a future column. Bad Medicine appears each Tuesday on LiveScience.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus