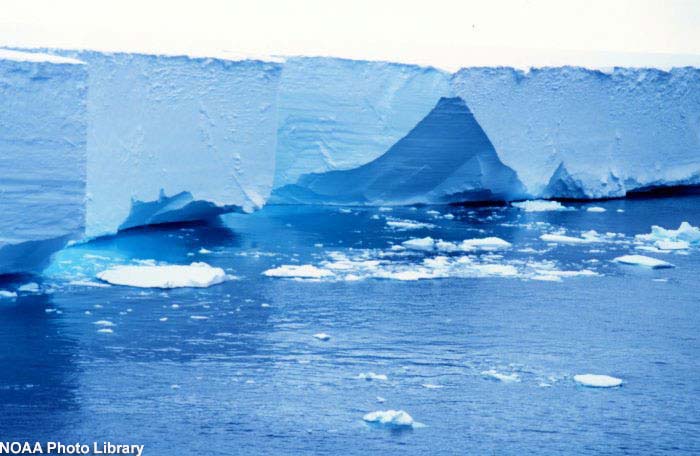

Is Antarctica Falling Apart?

Recent news of mammoth icebergs the size of small U.S. states breaking off Antarctica may sound dire. But those events mostly represent business as usual at the world's southernmost continent, scientists say.

A massive iceberg the size of the state of Rhode Island collided with Antarctica's Mertz Glacier in mid-February, and caused a huge new iceberg with an estimated mass of 860 billion metric tons to break off the glacial tongue. Scientists note that such dramatic examples have not been uncommon over the past decade.

"I need to stress that the event in the Mertz area, and indeed most of the iceberg calving in Antarctica is a completely normal, expected activity for a stable ice sheet," said Ted Scambos, a glaciologist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colo.

Biggest icebergs lately

Scambos described the Mertz glacial tongue iceberg as "large but not record-breaking," and pointed to a "real monster of a berg" that broke off the Ross Ice Shelf in 2000, called B-15. The 170 x 25 mile iceberg briefly rivaled the size of New York State's Long Island, or about the size of Connecticut.

Both large and small iceberg calving events represent the usual process [how it works] by which the ice sheet loses mass, according to Neal Young, a glaciologist with the Australian Antarctic Division that has been tracking the Mertz Glacier and the new iceberg, named C-28. He added that the last major calving event from the Mertz Glacier occurred somewhere between 50 and 100 years ago.

"The icebergs may calve as massive pieces infrequently, or as smaller pieces more frequently," Young told LiveScience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Young and other scientists spotted a flotilla of more than 100 smaller icebergs trekking toward New Zealand from Antarctica last November. They noted that the smaller bergs probably resulted from the breakup of a massive iceberg that broke off from the Ross Ice Shelf, not unlike B-15.

"There used to be reports from the clipper and other sailing ships of hundred years ago or so, of groups of many icebergs along their routes from time to time, and at other times no icebergs at all," Young said.

Recent shipping traffic has moved to the Panama and Suez canals in the lower latitudes closer to the equator, where icebergs rarely venture. That may be one reason why iceberg reports from ships have dropped in recent years, Young explained.

A 2008 study estimated that Antarctica loses about 1.6 trillion metric tons of ice each year, but gets nearly that much back as annual snowfall. The icy continent may suffer a net ice loss of about 100-200 billion metric tons per year, but Scambos said the exact figure remains uncertain.

In any case, the monster icebergs that grab headlines don't actually represent a greater-than-normal loss of ice for Antarctica, scientists say.

"To my knowledge there is no evidence that there is more net ice loss in these big bergs now than in the historic past," said David Long, a scientist at Brigham Young University who runs an iceberg tracking site.

More iceberg fragments

Long explained that the overall iceberg count has gone up in recent years, but mainly because of many smaller fragments. He and Scambos both cited improved satellite monitoring and iceberg tracking over the past 10 years.

One possible exception to business-as-usual comes from the Antarctic Peninsula at the northernmost part of the continent. A new report by the U.S. Geological Survey suggests that every ice front in the southern part of the Antarctic Peninsula — the coolest part of the peninsula — has been retreating overall from 1947 to 2009. The most dramatic changes have taken place since 1990.

All the scientists consulted by LiveScience also mentioned the Antarctic Peninsula's recent changes, which are mainly driven by warmer air temperatures.

Young pointed to the disappearance of the Larsen A and B ice shelves in the Antarctic Peninsula, and a large speed-up in glaciers that now discharge directly into the ocean rather than feed back into the ice shelves. He also referred to a loss of ice in glaciers near the Amundsen Sea sector of West Antarctica, where the ice sheet has also undergone the fastest rate of thinning.

Such ice-loss events contribute to sea level rise, although the overall contribution from the Antarctic Peninsula is small.

But Young noted that researchers remain concerned about the possible link between the loss of ice shelves and the speed-up of glaciers, because it represents a key uncertainty regarding how much the Antarctic ice sheet might contribute to future sea level rise.

- Photo Album: Antarctica, Iceberg Maker

- Is Mother Nature Out of Control?

- 101 Amazing Earth Facts

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus