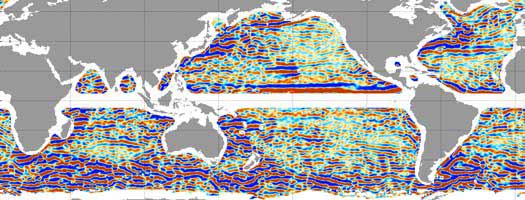

Seas Striped With Newfound Currents

Sailors and scientists have been mapping ocean currents for centuries, but it turns out they’ve missed something big. How big? The entire ocean is striped with 100-mile-wide bands of slow-moving water that extend right down to the seafloor, according to a recent study.

Nikolai A. Maximenko of the University of Hawaii at Manoa and colleagues developed a precise new method for measuring the topography of the ocean surface by combining data from satellites and from the movements of more than 10,000 drifting oceanographic buoys. In doing so, the team generated detailed maps, in which they first noticed the peculiar striations. Some scientists initially dismissed the stripes as statistical artifacts, but Maximenko’s team dug deeper, looking for a similar pattern in water temperature measurements from two test areas in the Pacific.

Indeed, though barely detectable, the striated currents are real. They flow past each other in opposing directions at 130 feet per hour—just one-tenth to one-hundredth the speed of major ocean currents—and subtle changes in temperature demarcate their boundaries.

Maximenko says a new computer model has corroborated some features of the observed striations, but his team is still mystified by their orientation, location, and strength. The discovery is important, he says, because even weak currents can have large effects on global climate and on the flow of food and creatures in the oceans.

The research was detailed recently in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

- 101 Amazing Earth Facts

- Hurricane Season Getting Longer

- Gallery: Underwater Explorers

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus