Odd Gender Differences Found in Walking

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

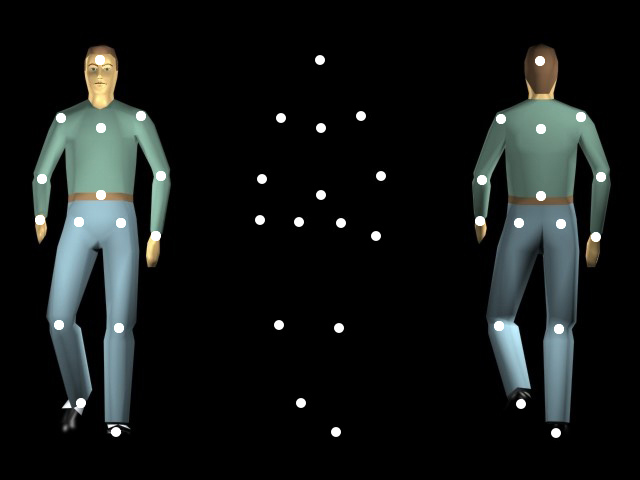

If we see a shadowy figure walking down a dark street, our sense of whether it is coming at us or walking away depends on whether we see it as a he or a she, new research finds. This new result sheds light on the subtle judgments the brain makes when it notices motion. In the past, research has shown that people are extraordinarily good at deducing the gender, age, mood and even personality of others based on just a few of their moves. "Humans are acute observers of each other. We know a lot about each other at first glance. How we do that is an interesting question, especially as some people seem so good at it," said researcher Rick van der Zwan, a behavioral neuroscientist at Southern Cross University in Australia. To see what other kinds of details people might glean from movements, scientists had volunteers watch clusters of dots shaped roughly like people. These were created by attaching lights on the real people and filming them as they either walked on a treadmill toward or away from a camera. "If you look at someone with just their joints illuminated when they aren't moving, it's difficult to tell what it is you are looking at. But as soon as they move, instantaneously, you can tell that it's a person and perceive their nature," van der Zwan said. "You can tell if it's a boy or a girl, young or old, angry or happy. You can discern all these qualities about their state, affect, and actions with no cues at all about what they look like — with no form at all, just motion." As these stylized figures walked, their movements were manipulated to range anywhere from a "girly girl" to a "hulking male." The halfway point was a gender-neutral walker that volunteers judged as male half the time and female the other half. Oddly, when these ambiguous figures were judged as masculine, volunteers saw them as approaching them, even when the actual people these figures were based on had walked away from the camera. Moreover, when these figures were judged feminine, volunteers saw them as walking away from them, even when in real life the women had approached the camera. "The thing that most people find most surprising is that the effects are consistent for observers of both genders," van der Zwan told LiveScience. "It does not matter if you are a female or a male observer — male figures of the type we used often look like they are facing the observer and female figures often look like they are facing away." Apparently, "there is something in the way males and females move that affects the way others see them in terms of their orientation in space," van der Zwan said. It is "tempting to speculate" that this effect reflects the potential costs "of misinterpreting the actions and intentions of others," he added. "For example, a male figure that is otherwise ambiguous might best be perceived as approaching to allow the observer to prepare to flee or fight. Similarly, for observers, and especially infants, the departure of females might signal also a need to act, but for different reasons." The scientists will detail their findings in the Sept. 9 issue of the journal Current Biology.

- Video – Walk This Way

- Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind

- The Amazing Complexity of Getting Around

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus