Rival Sperm Hook Up and Cooperate

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

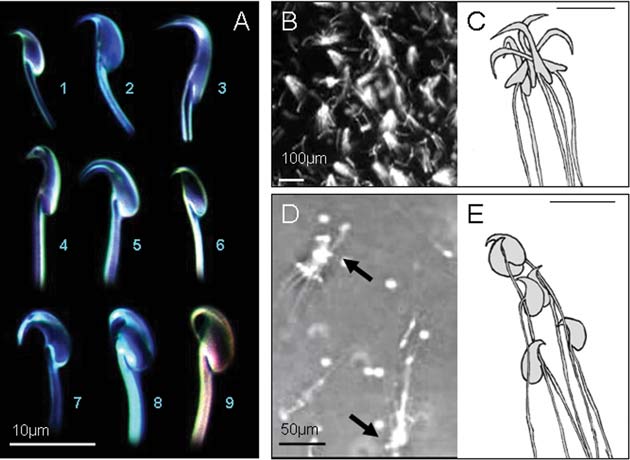

Rats and mice have unusual sperm, possessing heads shaped like talons.

Scientists now reveal the larger the testicles of a rodent are, the more likely the sperm of that species are to curve like a claw [image]. Researchers suggest the sperm use these hooks to snag each other and form speedy "trains" that cooperate to reach the egg first.

In mammals, the heads of sperm are usually shaped like paddles to presumably help them swim. Scientists had long puzzled over the scythe heads of the sperm of mice and their close relatives.

Faster together

A past study had revealed that in one rodent species, the European woodmouse Apodemus sylvaticus, sperm could hook up into trains of up to 100. These swim faster than solitary sperm competitors.

Normally sperm cells in each male are rivals, with millions racing each other to reach the finish line first. Their struggles hopefully ensure that only healthy sperm end up fertilizing eggs.

Evolutionary biologist Simone Immler of the University of Sheffield in Britain and her collaborators reasoned there are times when sperm might want to cooperate. This might prove especially likely when animals are promiscuous and the sperm of one male have to compete against those of rival males.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To test their idea, the researchers investigated the sperm and promiscuity of 37 rodent species [video]. They calculated how frisky a species was by measuring testicle mass.

"Males in promiscuous species are better off by investing more into sperm production," Immler told LiveScience. "Hence, it has been shown that more promiscuous species have generally relatively larger testes."

Hooking up

The scientist found the more promiscuous a species was, the more hooklike the heads of their sperm were. Moreover, they saw the sperm of the Norway rat Rattus norvegicus and the house mouse Mus musculus group up.

"When the finding of the European woodmouse was published a few years ago, it appeared to be an exceptional case occurring in this one species only," Immler said. "This research shows that when the pressure from rival males is high, individual sperm will cooperate with one another to ensure that at least one of their siblings successfully reaches the female egg."

Sperm cooperation is also found in some North American possums and in some insects. "Sperm cooperation might be much more widespread than assumed so far," Immler said.

Immler and her colleagues reported their findings online Jan. 24 in the journal PLoS ONE.

- Video: The Rat Sperm in Action

- Sniff and Swim: How Sperm Find Eggs

- Longest Known Sperm Create Paradox of Nature

- Mating Game: The Really Wild Kingdom

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus