How Penguins Got Their Cold-Weather Coats

Those tuxedo-wearing birds that inhabit Earth's coldest continent may have evolved a means of retaining heat when they were still living in warm climates, scientists now suggest.

A key adaptation that helped modern penguins to invade the cold waters of Antarctica within the last 16 million years is the so-called humeral arterial plexus, a network of blood vessels that limits heat loss through the wings.

The plexus routes blood coming into the body from the wings past the blood traveling from the body to the wings. As such, the cooler blood from the wings, which get cold in the water, is heated up by warmer blood from the body, thus conserving heat.

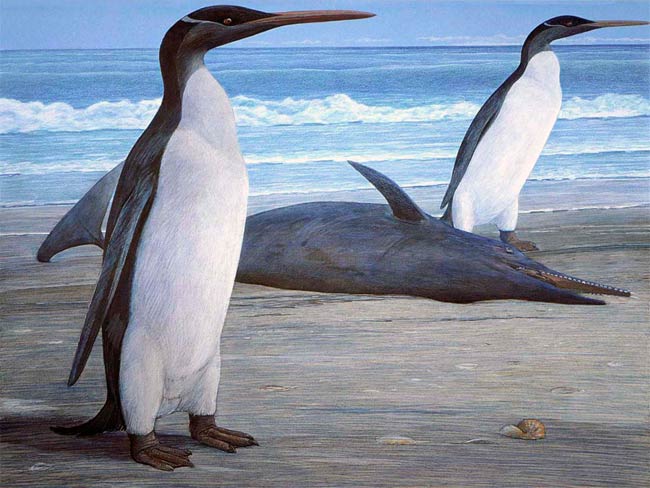

To find out more about how this anatomical structure evolved, scientists investigated seven live penguin species and 19 fossil ones. In live specimens, they found the plexus leaves behind grooves in the upper arm bone called the humerus. As such, they could see when this structure began appearing in extinct penguin species from the fossil record. [Image of extinct penguin]

Surprisingly, they found the plexus arose at least 49 million years ago, when the planet was going through a warm "greenhouse Earth" phase due to vast amounts of global warming gases that got pumped into the atmosphere, perhaps by volcanism.

"I began this work thinking we would relate heat retention in penguins to the global cooling that took place at the Eocene-Oligocene boundary [about 34 million years ago], whereas in fact, penguins were cold-water-tolerant millions of years earlier," researcher Daniel Thomas, a paleontologist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, told LiveScience.

The earliest known penguins to feature the plexus lived on the lost continent of Gondwana, on what is now Seymour Island in Antarctica. Back then, the waters there were 59 degrees Fahrenheit (15 degrees Celsius), compared with the water's current average temperature of 34 degrees F (1 degree C). (Scientists can deduce ancient temperatures by looking at the chemistry of fossils — for instance, magnesium levels in the shells of certain organisms rise as temperatures go up.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers suspect the plexus first evolved to help penguins save energy during long foraging trips in the cold water, as the structure evolved in concert with dramatic skeletal changes that promoted buoyancy and reduced drag, thus improving deep-diving and long-distance swimming. As global climate cooled, the plexus then found a new use, proving key to the penguins' invasion of Antarctic ice sheets.

"Penguins have occupied much of the Southern Hemisphere in the last 40 million years because of their tolerance for cold water," Thomas said.

Thomas and his colleagues Dan Ksepka and Ewan Fordyce detailed their findings online Dec. 22 in the journal Biology Letters.

- Flightless Birds: A Gallery of All 18 Penguin Species

- North vs. South Poles: 10 Wild Differences

- Top 10 Monogamous Animals