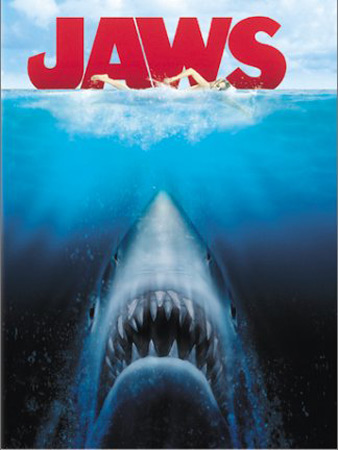

How 'Jaws' Forever Changed Our View of Great White Sharks

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When "Jaws" burst onto movie screens on June 20, 1975, the film shocked audiences with a terrifying monster.

Now, 35 years later, the slogan "Don't go in the water" from the movie has turned out to be a lousy PR campaign for sharks, whose numbers worldwide have been decimated due partly to the frightening and false ideas the film helped spread about them.

Although sharks certainly have a fearsome reputation nowadays, incredibly, "at the turn of the 20th century, there was this perception that sharks had never attacked a human being," said George Burgess, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research in Gainesville. "There was even a reward offered if someone could prove they were bitten by a shark — money that was never collected."

That began to change when a deadly rampage by a rogue great white shark on swimmers along the New Jersey shoreline and in a nearby creek during the summer of 1916 — attacks that helped inspire "Jaws," Burgess noted.

"Perceptions especially changed during World War II, when a lot of people were put out to sea, and stories of shark attacks after ships or airplanes going down rose," he explained. "So there was this stereotype of sharks being man-eaters that had to be looked out for."

The film's key mistake was portraying great white sharks as vengeful predators that could remember specific human beings and go after them to settle a grudge.

"The movie certainly gave sharks too much of an ability to engage in revenge," Burgess said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As a consequence of this depiction of sharks as monsters bent on massacring swimmers and boaters in "Jaws," dozens of shark fishing tournaments popped up. "A collective testosterone rush certainly swept through the East Coast of the U.S.," Burgess said. "It was good blue-collar fishing. You didn't have to have a fancy boat or gear — an average Joe could catch big fish, and there was no remorse, since there was this mindset that they were man-killers."

"The movie helped initiate that decline by making it sexy to go catch sharks," Burgess said.

One inadvertent benefit linked with this calamitous drop in shark numbers was that scientists became aware of the need to learn more about sharks. This resulted in increased funding for shark research, improving our understanding of shark biology.

"Up until that point, there was virtually no funding for sharks, because they were not thought particularly interesting to humans, not being a major food fish — they were regularly regarded as a pest or nuisance that ate the baits or catches of commercial fishermen," Burgess said.

Now researchers know more about contributing factors to shark attacks, "so we're smarter when it comes to avoiding certain situations, and have minimized the number of attacks over the years," Burgess said. "Our medical capabilities are also far better than 100 years ago, so even when shark attacks occur, the consequences are not as severe — if bitten, the fatality rate was 40 to 50 percent in the early part of the 20th century, and now it's down to 10 percent."

"I think nowadays that there is a more enlightened view that sharks are part of the environment, and that you have to look out for sharks as you would for anything else in a wilderness experience," Burgess said.

"Still, there are some people who don't want to put their feet into the water as a result of seeing 'Jaws,'" he added.

- Jaws of Death: 10 Reasons Great White Sharks Are Great

- Shark Science on the 35th Anniversary of 'Jaws'

- How ‘Jaws’ Changed Summer Movies Forever

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus