Something's Missing: Penis-Less Worm Discovered in Spain

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A new worm discovered on the Iberian Peninsula is missing something: a penis.

The tiny nematode, found in a compost pile, mates without penetration. Instead, it pumps a capsule full of sperm out of an opening in its body and into a funnel-like structure on the female's vulva. From there, the sperm enter the female's reproductive tract to fertilize her eggs.

"We are sampling [the whole] Iberian Peninsula from several decades ago, and we never found a similar species, and, [with] respect to other countries, it is very rare that other researchers find some species of this genus," Joaquín Abolafia, a biologist at the University of Jaén and the discoverer of the new species, wrote in an email to Live Science. "For that reason, this discovery is surprising." [See Photos of a Phallic-Shaped Worm Missing Link]

Second skin

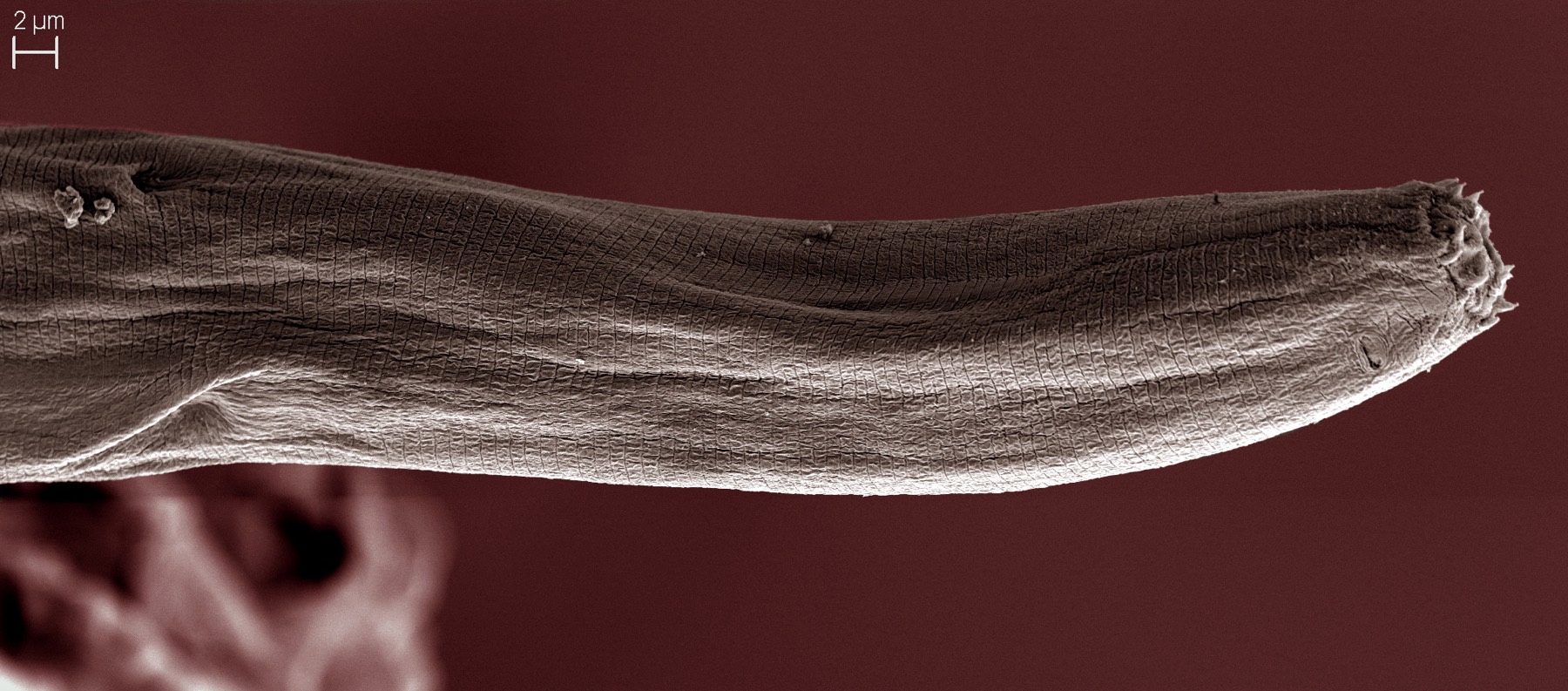

The worm is unlike other nematodes in ways other than its weird genitals. (More commonly, nematode males have penis-like organs called spiculesthat the animals use to penetrate females.) This newfound worm also has two layers of skin, or cuticle, one of which comes from the worm's juvenile moult. Instead of fully shedding the skin, the creature keeps the layer attached. This second skin protects the worm from drying out in the arid summers of the Iberian Peninsula, the researchers reported in December in the journal Zootaxa.

The worms also have asymmetrical buccal cavities, or mouths, while most nematodes have symmetrical mouths, Abolafia said.

Abolafia and his colleagues discovered the worm during a study of the biodiversity of the dry southern Iberian. They found the creature in a compost pile in an orchard near the city of Jaén, living alongside another previously unknown nematode, Protorhabditis hortulana. That worm is notable for being one of the smallest soil nematodes ever found, reaching just 222 micrometers in length, Abolafia said.

Superfluous penis

The researchers dubbed the new species Myolaimus ibericus. Members of the genus Myolaimus are rare, Abolafia said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"At present, only 15 species have been found belonging to this genus," he said, "and most of them only have been recorded once."

The newly discovered worm is tiny, growing to only about 0.03 inches (0.8 millimeters) in length.

M. ibericus' odd genitals may have evolved due to mating competition, Abolafia said. The worm's spermy, glue-like secretions are similar to the "mating plugs" used by some species to plug the female reproductive tract after sex. That action prevents another male from coming in and displacing the first male's sperm after the fact. Unable to penetrate these mating plugs, spicules may have become superfluous and simply disappeared, Abolafia said.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus