Brutally Murdered Pictish Man's Face Gets Digitally Recreated

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

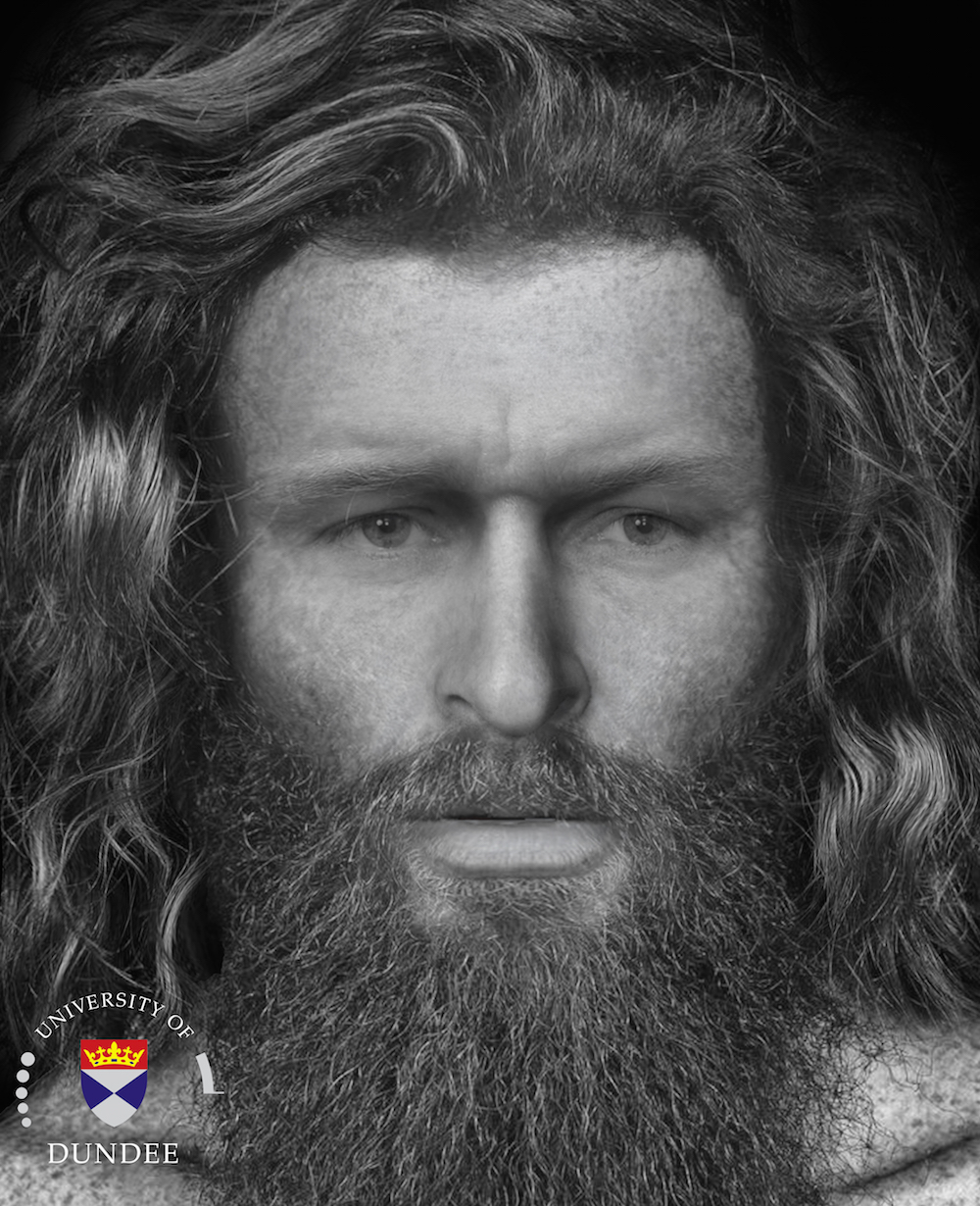

The face of a 1,400-year-old murder victim is seeing the light of day, now that scientists have digitally reconstructed his features.

The victim, a young Pictish man, met a grisly end when he was brutally murdered in what is now modern Scotland. Archaeologists found the man's remains — placed in an odd, cross-legged position with rocks pinning down his arms and legs — during the excavation of a cave in the Black Isle, Ross-shire, in the Scottish Highlands.

The archaeologists sent the man's bones to the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification (CAHID) at the University of Dundee in Australia. The team there, led by forensic anthropologist Sue Black, analyzed the bones and identified the horrific injuries the man had sustained, including five impacts that led to the fracturing of the man's face and skull. [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

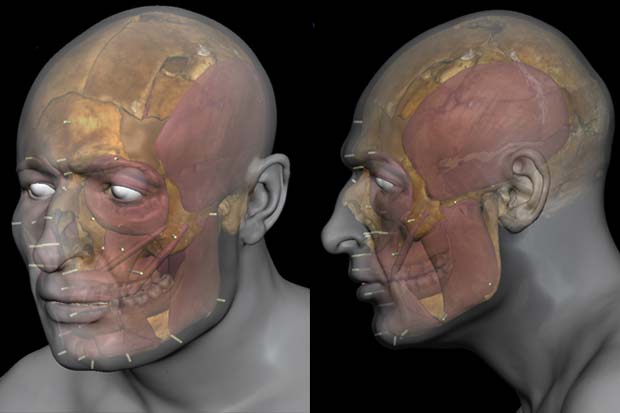

And then, they created a digital reconstruction of his face, Black said.

"This is a fascinating skeleton in a remarkable state of preservation, which has been expertly recovered," Black said in a statement. "From studying his remains, we learned a little about his short life, but much more about his violent death. As you can see from the facial reconstruction, he was a striking young man, but he met a very brutal end, suffering a minimum of five severe injuries to his head."

The man's injuries indicate that a tool with a circular cross section made the first injury "that broke his teeth on the right side," Black said. "The second may have been the same implement, used like a fighting stick, which broke his jaw on the left. The third resulted in fracturing to the back of his head as he fell from the blow to his jaw with a tremendous force, possibly onto a hard object, perhaps stone."

The fourth impact was likely meant to end the man's life, she said. The attacker, or attackers, drove the same weapon through the man's skull, "from one side and out the other as he lay on the ground," Black said. "The fifth was not in keeping with the injuries caused in the other four, where a hole, larger than that caused by the previous weapon, was made in the top of the skull."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Radiocarbon dating of a bone sample showed that the man died between A.D. 430 and 630, a time known as the Pictish period in Scotland.

In addition, workers surveying the cave where archaeologists found the man's body unearthed hearths and iron-working debris, suggesting that the cave was used for iron smithing during the Pictish period, Black said. But the murdered man's body puts a new perspective on how ancient people used the cave, Black and her colleagues said.

"Having specialized in prehistoric cave archaeology in Scotland for some years now, I am fascinated with the results," Steven Birch, the excavation leader, said in the statement. "Here, we have a man who has been brutally killed, but who has been laid to rest in the cave with some consideration — placed on his back within a dark alcove and weighed down by beach stones."

"While we don't know why the man was killed," Birch added, "the placement of his remains gives us insight into the culture of those who buried him. Perhaps his murder was the result of interpersonal conflict; or was there a sacrificial element relating to his death?"

Researchers may soon learn more about the doomed man; the goal of the Rosemarkie Caves Project is to search more caves in the Black Isle, continuing to survey caves along the isle's coast.

Several other small excavations that were done in the past few years show that these caves were occupied or utilized in some way from about 1,500 to 2,000 years ago.

What's more, the caves have artifacts that date from about 200 to 300 years ago, likely left behind by temporary travelers or more permanent occupants. Some of these more recent occupants were likely making or repairing leather shoes for local communities, evidence suggests.

Black and her colleagues plan to continue to study the skeleton and artifacts left in the cave, with the hope of learning more about the man's place of origin, she said.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus