One Breath Into This Breathalyzer Can Diagnose 17 Diseases

A single breath into a newfangled breathalyzer is all doctors need to diagnose 17 different diseases, including lung cancer, irritable bowel syndrome and multiple sclerosis, a new study found.

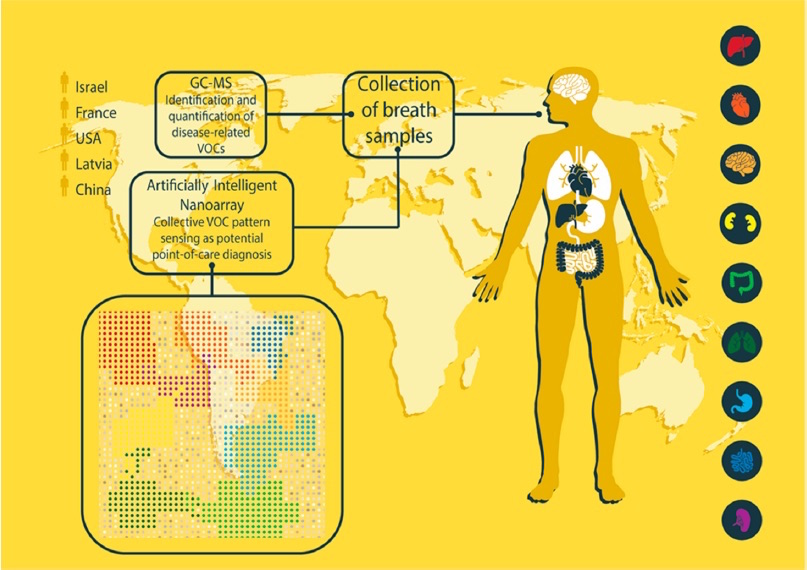

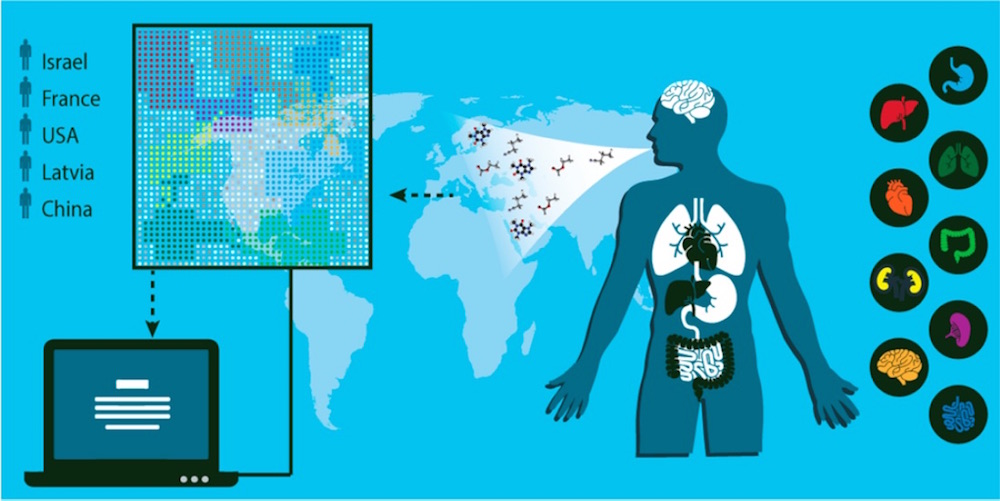

Researchers invited about 1,400 people from five different countries to breathe into the device, which is still in its testing phases. The breathalyzer could identify each person's disease with 86 percent accuracy, the researchers said.

The technology works because "each disease has its own unique breathprint," the researchers wrote in the study. [10 Crazy New Skills That Robots Picked Up in 2016]

The breathalyzer analyzes microscopic compounds — called volatile organic compounds (VOCs) — to detect each condition. Testing for VOCs isn't a new approach; in 400 B.C., physicians learned that smelling a patient's bodily emissions could help with diagnoses. For instance, doctors used to smell the stools and urine of infant noblemen daily, the researchers said.

But while excrement and other bodily substances, such as blood, contain VOCs, examining exhaled breath is the cheapest, easiest and least invasive way to test for the compounds, the researchers said.

Breath evaluation

To investigate using breath for diagnosis, the researchers developed a breathalyzer that had two nanolayers, one with carbon and the other without. The carbon-free layer contained modified gold nanoparticles and a network of nanotubes, both of which provide electrical conductivity, the researchers said.

Meanwhile, the carbon layer worked as a sensing layer to hold the exhaled VOCs, the scientists said. When a person breathed into the breathalyzer, that individual's VOCs interacted with the organic sensing layer, which in turn changed the electrical resistance of the inorganic sensors. By measuring this resistance, the researchers could determine which VOCs were present, the scientists said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

There are hundreds of known VOCs in exhaled breath, but the researchers needed only 13 to distinguish among the 17 different diseases. For instance, the VOC nonanal is linked to several disorders, including ovarian cancer, inflammatory bowel disease and breast cancer, whereas the VOC isoprene is associated with chronic liver disease, kidney disease and diabetes, the researchers said.

Because each VOC is tied to several conditions, "These results support our finding that no single VOC can discriminate between different diseases," the researchers wrote in the study.

Exhale here

Once the breathalyzer was built, researchers administered it to 813 people who were diagnosed with one of the 17 diseases, as well as 591 controls. These were people from the same locations who did not have those diseases. All of the participants were in China, Israel, France, Latvia or the United States, the researchers said.

Next, the scientists used artificial intelligence to tally up the VOCs in each breath, search a database for diseases showing the same VOC concentration patterns and deliver a diagnosis. [Gallery: The BioDigital Human]

The results were blinded, meaning that, during the analysis, the researchers did not know which condition the participants had. Moreover, the research team verified its results with another method that measured the VOCs in each sample.

The new breathalyzer isn't ready for the market yet — further testing and better accuracy are needed first — but the study is an encouraging development, the researchers said.

If it's made available to doctors, the device could be an "affordable, easy-to-use, inexpensive and miniaturized [tool] for personalized screening, diagnosis and follow-up," the researchers wrote in the study, which was published online Dec. 21 in the journal ACS Nano.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.