Bizarre Fish Are Deadly Deep-Sea Predators (And Twitter Stars)

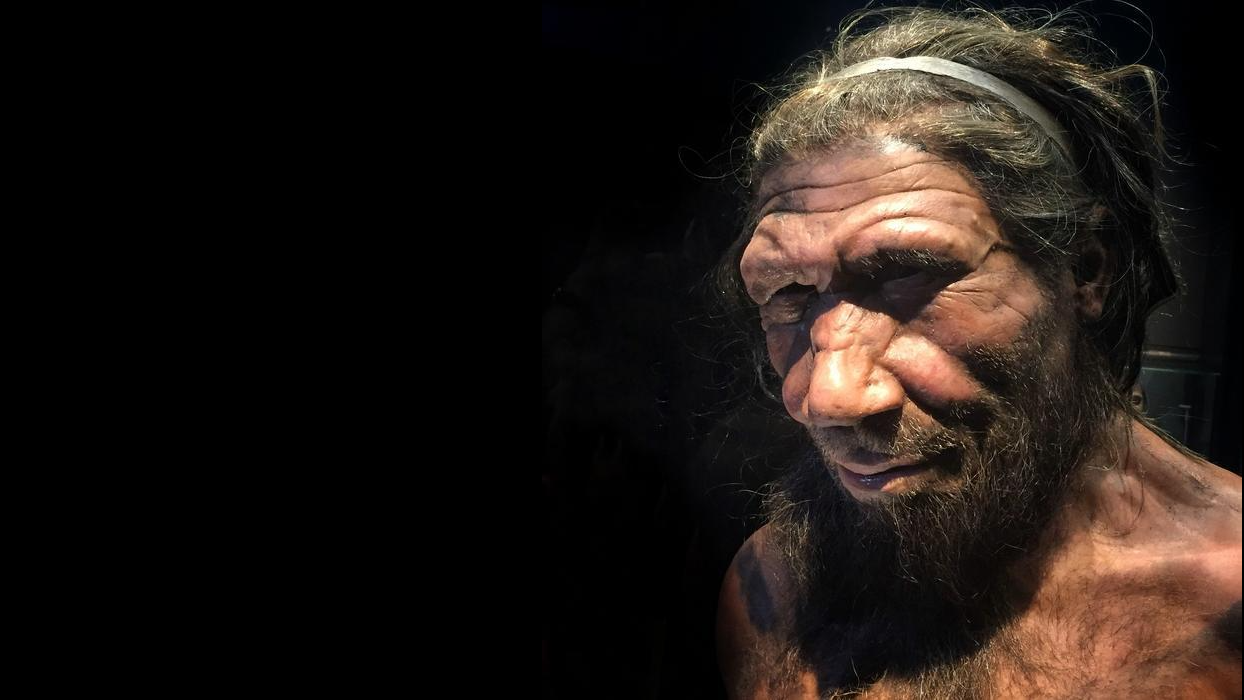

Pictured above: A frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus anguinensis), identified by John Sparks, curator of ichthyology at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH).

Blobby fish with bulging and reflective eyes, protruding jaws crammed with spiky teeth, and peculiar structures dangling from bodies are finding an appreciative audience on land. That's because a Russian fisherman named Roman Fedortsov shared photos on Twitter of these mysterious denizens of the deep.

Fedortsov hails from Murmansk, a port city on Russia's northwest coast near the Barents Sea, according to his Twitter bio. He works on a type of net-fishing boat called a trawler, and he photographs and tweets — in Russian —about the unusual fish and occasional invertebrates that he finds, which typically live in deep water but are pulled to the ocean surface in the trawler's wide-mouthed nets.

Some of the fish are a deep, inky black, while others are translucent, and several have eyes that appear to glow. Although these creatures' looks might appear nightmarish and grotesque to surface-dwellers, their peculiar features are adaptations that allow them to thrive in the cold and dark ocean depths. [In Photos: Spooky Deep-Sea Creatures]

Fish that live in the deep-ocean region called the mesopelagic zone, which ranges from depths of about 650 to 3,300 feet (200 to 1,000 meters), may swim closer to the surface to feed. But when they're way down deep, these fish navigate waters that are much colder and darker than those in shallower marine environments, said John Sparks, a curator in the ichthyology department at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Sparks, who does not work with Federetsov, told Live Science that the features that make deep-sea fish look so strange — coloration so dark it seems to swallow light, oversized lower jaws and long, spiky teeth — are optimized for a dim habitat where food is scarce.

The dark, velvety-black color of some predators helps them to stay hidden, even if they have just swallowed a bellyful of prey that glows, Sparks said. Many deep-sea creatures are bioluminescent, shimmering with a light they generate internally. For a fish that eats bioluminescent animals, inky skin acts like a blackout curtain over its stomach, keeping a predator's last meal from giving its position away to the next potential meal, he explained.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Pictured above: A female deep-sea anglerfish (Ceratioidei), commonly known as a "sea devil," identified by John Sparks (AMNH).

Protruding lower jaws and sharp, spiky teeth are also frequently seen in deep-sea fish, because these features help to snag wriggling prey, Sparks said. With scant light to show where likely prey might be found, a predator's best strategy is to sit and wait for an unsuspecting fish to swim by and then snap it up in a single gulp.

"It's a stealth environment," Sparks told Live Science. "You don't have to be streamlined and fast. You can be a lie-and-wait ball of flesh with a big gape and dagger-like teeth. If you have a big jaw that unhinges — almost 180 degrees — no matter what prey you encounter, you can grasp it with your teeth."

Pictured above: A female deep-sea anglerfish, likely family Linophrynidae and genus Haplophryne, sometimes called "ghostly seadevil." Identified by John Sparks (AMNH).

An expanding stomach also benefits a fish that must gulp down whatever crosses its path. Such a stomach can even enable a predator to swallow prey larger than its own body, Sparks said.

One extreme example, the aptly named black swallower (Chiasmodon niger), has a stomach that stretches so much that digestion can become a race against time — and the swallowers sometimes lose. Sparks said that these fish have been found dead with their bellies full of meals that decomposed before they could be digested, killing the swallowers.

Some of the fish in Fedortsov's photos have enormous eyes or eyes that seem to catch and reflect light. But what's really interesting about fish that live in a perpetually dark environment is that there's so much variability in the types of eyes that they have — some are big, some are small, and some are even fluorescent, Sparks told Live Science. There's a lot that scientists have yet to discover about how these animals' vision functions in dark water, he added.

Pictured above: A grenadier or rattail in the Macrouridae family. It is a deep sea gadid — a type of cod — and most have a bioluminescent organ on their ventrum. Identified by John Sparks (AMNH).

Much has been learned about mesopelagic fish in the past several decades, but many questions remain, Sparks said. One question scientists want to answer is how so much diversity in deep-sea fishes emerged in an environment with no natural boundaries to separate populations and drive speciation.

"The thinking used to be that because the deep sea is a very homogeneous environment in terms of temperature and salinity, that there were just a few species but that they were very widespread," Sparks explained.

"But when we looked more closely at the morphology and genetic data, diversity was higher than we thought. It's a very species-rich environment — the question is, how are they diversifying?"

For some people, a single glimpse of these unusual fish may be more than enough. But if you want more, you're in luck: Federotsov has shared plenty of images on Twitter and Instagram.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.