Oldest Known Avian 'Squawk Box' Helped Ancient Bird Quack

More than 66 million years ago, a duck-size waterbird flew around the woods of ancient Antarctica, honking and calling to its mate with what is now the oldest discovered avian vocal organ on record, a new study finds.

The findings also suggest that dinosaurs, for which no vocal organ has been found, likely didn't sing and tweet like birds do.

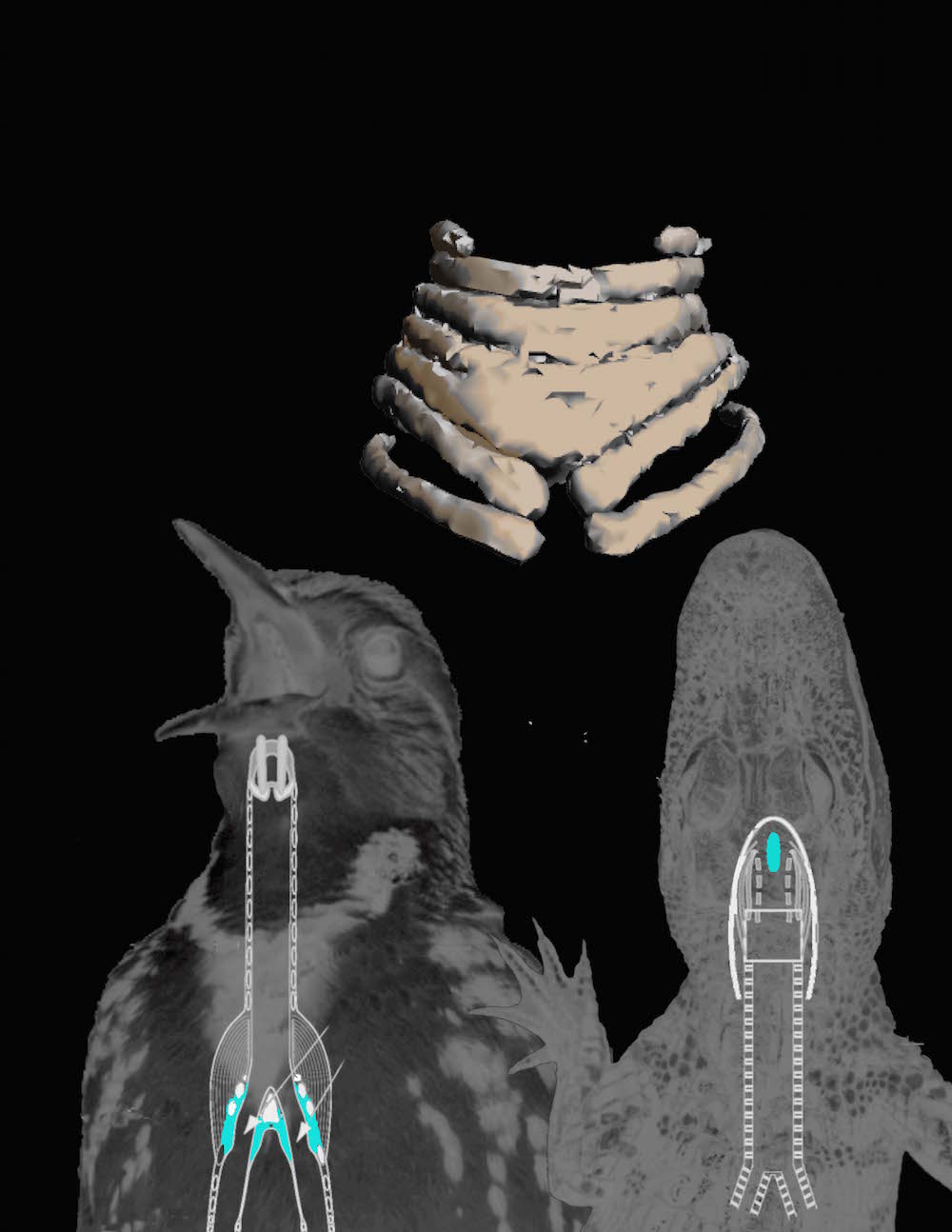

The vocal organ, known as a syrinx, is tiny: about the width of a pencil and less than 0.3 inches (1 centimeter) tall. But it's an enormous finding for experts piecing together the evolutionary history of birds, said lead study researcher Julia Clarke, a professor of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Texas at Austin.

"This is the avian vocal organ, which is unique amongst all vertebrates," Clarke told Live Science. "There's virtually nothing written about its origin or early evolution." [Avian Ancestors: Images of Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly]

The newly discovered syrinx belonged to Vegavis iaai, a Cretaceous-age bird found on Antarctica's Vega Island. Researchers from the Argentine Antarctic Institute found specimens of the bird in 1992 and sent the fossils to Clarke to examine. In previous work, detailed in a 2005 study in the journal Nature, Clarke and her colleagues found that the bird is related to modern ducks and geese.

In 2013, Clarke was looking at the micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scans of one of the 1992 Vegavis iaai specimens when a tiny detail caught her attention. It was the syrinx.

"I had actually started thinking about the fossilization potential of the syrinx," Clarke said. "I was shocked to find that this fossil, which had actually been in my lab for a number of years, had a fossil syrinx."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Syrinx sounds

Modern birds have many types of syrinxes, but in general, the organ sits where the two branches of the bird's windpipe fork apart and head toward the lungs. The windpipe's branches can vibrate the syrinx's soft tissues at different frequencies, which is why birds can "sing" two different notes at the same time.

The researchers scanned the syrinxes of 12 modern birds and a 50-million-year-old fossilized syrinx from Wyoming dating to the Eocene epoch. The scientists found that the V. iaai syrinx is asymmetrical, much like that of a modern female duck. This suggests that the extinct bird made honking, quacking or whistling noises with the right and left branch of the organ, the researchers said.

The finding confirms that the syrinx evolved during the Mesozoic Era, the age of the dinosaurs, Clarke said. Now that scientists know that the syrinx — which is made of cartilage and often degrades too easily to remain in the fossil record — can be preserved, it's unclear why no syrinx remains have been found in dinosaurs, the researchers said.

Perhaps birds, which evolved from the mostly meat-eating, bipedal theropod dinosaurs, developed the syrinx after they learned to fly and acquired improvements in breathing and metabolism that helped it fly and sing, the researchers said. This suggests that dinosaurs did not have syrinxes, and so couldn't sing like birds do, the scientists added.

Instead, dinosaurs likely produced booms, coos and hoots with closed-mouth vocalizations, said a July 2016 study that Clarke and her colleagues published in the journal Evolution.

The evolution of the vocal organ may give insights into other anatomical avian features. For instance, the development of complex mating systems is usually associated with increases in brain size in other vertebrates, including humans, the researchers said in the study. It's possible that birds brains evolved as birds began to use feathers and later birdsong for sexual selection, the researchers said.

But for now, Clarke's team is working with engineers to create a model that will help them understand the ancient sound-producing organ.

The findings were published online today (Oct. 12) in the journal Nature.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.