Ancient Skeleton Found on Famed Antikythera Shipwreck

A well-preserved 2,000-year-old skeleton of a young man found on the famous Antikythera shipwreck could provide the first DNA evidence recovered from an ancient sunken boat, archaeologists reported.

Divers discovered the skeletal remains of the man, possibly a crewmember of the ship, on Aug. 31 during an excavation of the Antikythera shipwreck. This is where the mysterious Antikythera mechanism (an astronomical calculator) was found, in the Aegean Sea, near the Greek island of Antikythera. The submerged ruins date to 65 B.C and are thought to belong to a Greek ship that was used for trading or cargo.

Many precious artifacts as well as human remains have emerged from the wreckage of this ancient seafaring vessel since the ship was first discovered, in 1900. But for the first time, scientists are capable of conducting genetic analysis of a recovered skeleton, a procedure that was not yet available for bones found during a 1976 expedition, according to a Sept. 19 statement released by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in Massachusetts, whose researchers co-led the recent excavation. [Photos of Famed Antikythera Shipwreck and Antikythera Mechanism]

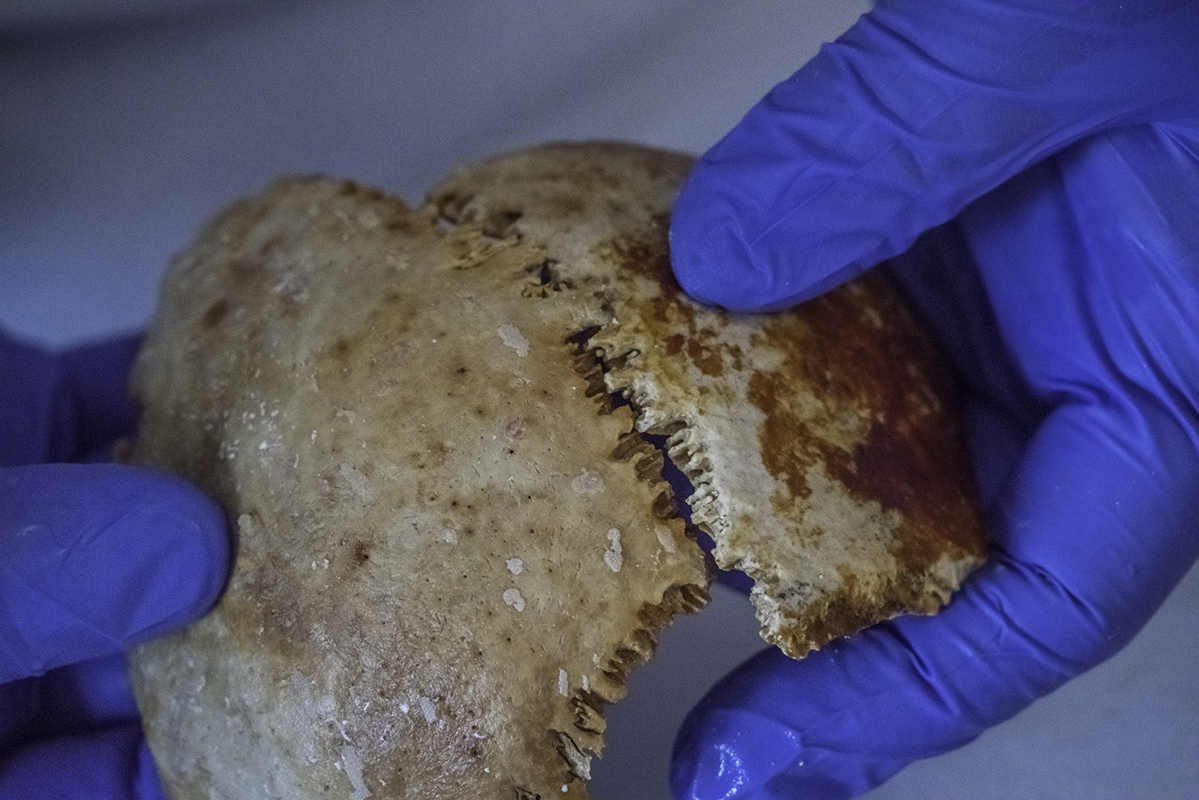

The bones, which were found buried beneath sand and bits of pottery, included rib pieces, two femurs, two arm bones and parts of a skull with three teeth still attached, and were described in a Sept. 19 news story published in the journal Nature. The bones' condition was described as "incredible" in a statement by Hannes Schroeder, an expert in ancient DNA at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen.

Schroeder traveled to Antikythera to view the bones after they were collected, determining that they likely all belonged to the same person — a young man, Schroeder said.

The skull pieces looked especially promising for DNA extraction, because they contained petrous bone, or a pyramid-shaped part of the temporal bone, Schroeder noted in the statement. Located at the base of the skull, this area contains some of the densest bone material in the body and is considered one of the best places for finding preserved DNA, which could inform researchers about what the young man looked like, or what part of the world he came from.

Since the shipwreck was first spotted by sponge divers more than 100 years ago, numerous objects have been brought to the surface. The first expeditions, in 1901, found treasures galore: dozens of marble statues, skeletons belonging to the long-dead crew and the spectacular bronze "computer" dubbed the Antikythera mechanism.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This peculiar device, described by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports as the most complex ancient item ever discovered, was found in 80 pieces. It contained wheels, dials and more than 30 gears. The complexity and intricate design intrigued and puzzled experts for decades; they eventually discovered that it was capable of showing lunar phases and the positions of the sun, moon and planets on a given date.

Other objects that emerged from the shipwreck appeared to be luxury goods belonging to people who enjoyed a lavish lifestyle: board-game pieces, musical instruments and even the arm of what may have been a bronze throne.

But while objects found at the site provide important information about how people lived thousands of years ago, the newly discovered skeleton represents a vital link to humans from the distant past — particularly those who crewed this ancient vessel, said Brendan Foley, a WHOI marine archaeologist who participated in the 2016 excavation.

"We can now connect directly with this person who sailed and died aboard the Antikythera ship," Foley said in the statement. "We don't know of anything else like it."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus