Human Ears Evolved from Ancient Fish Gills

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Your ability to hear relies on a structure that got its start as a gill opening in fish, a new study reveals.

Humans and other land animals have special bones in their ears that are crucial to hearing. Ancient fish used similar structures to breathe underwater.

Scientists had thought the evolutionary change occurred after animals had established themselves on land, but a new look at an old fossil suggests ear development was set into motion before any creatures crawled out of the water.

The transition

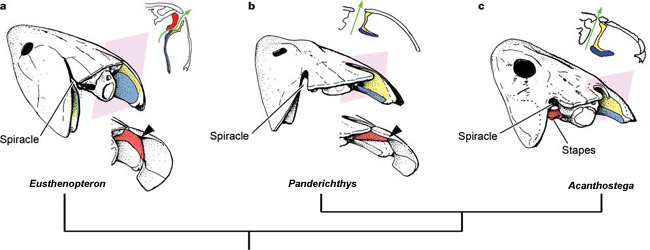

Researchers examined the ear bones of a close cousin of the first land animals, a 370-million-year-old fossil fish called Panderichthys. They compared these structures to those of another lobe-finned fish and to an early land animal and determined that Panderichthys displays a transitional form.

In the other fish, Eusthenopteron, a small bone called the hyomandibula developed a kink and obstructed the gill opening, called a spiracle.

However, in early land animals such as the tetrapod Acanthostega, this bone has receded, creating a larger cavity in what is now part of the middle ear in humans and other animals.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Missing link

The new examination of the Panderichthys fossil provides scientists with a critical "missing link" between fish gill openings and ears.

"In Panderichthys, it is much more like in tetrapods where there is no longer such a 'kink' and the spiracle has widened and opened up," study co-author Martin Brazeau of Uppsala University in Sweden told LiveScience. "[The hyomandibula] is quite a bit shorter, but still fairly rod-like like in Eusthenopteron. It's like a combination of fish and tetrapods."

However, it's unclear if early tetrapods used these structures to hear. Panderichthys most likely used their spiracles for ventilation of either water or air. Early tetrapods probably passed air through the opening. Scientists would need preserved soft tissue to say for sure.

"That's the question that we're starting to investigate, whether early tetrapods used it for some ventilation function as well," Brazeau said. Whether it was for the exhalation of water or air, it's not really clear. We can infer that it's quite expanded and improved from fish."

This research is detailed in the Jan. 19 issue of the journal Nature.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus