The Unexplored Brain: Nearly 100 Uncharted Areas Revealed

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

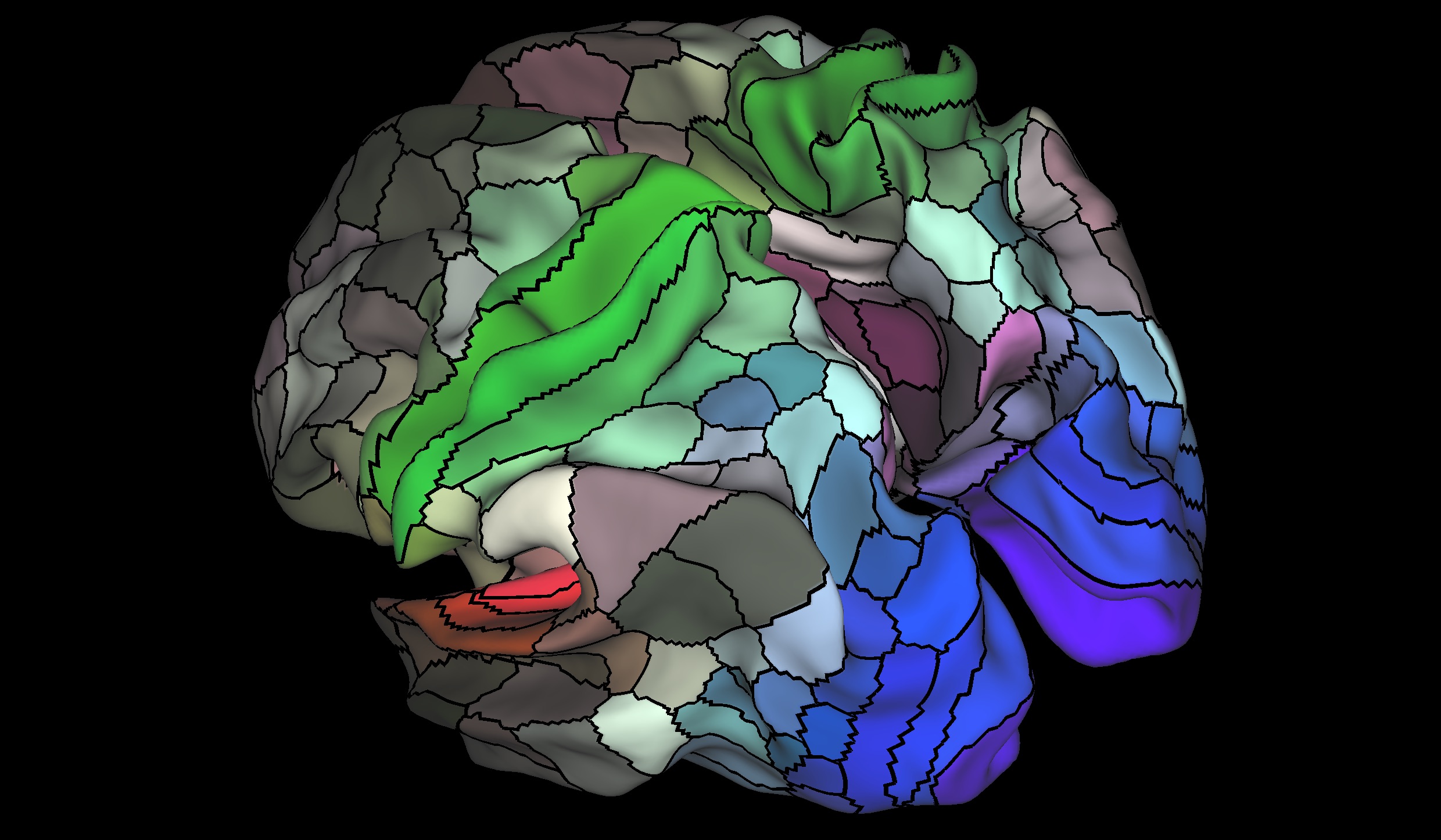

A detailed new map of the human brain's outer layer identifies nearly 100 brain areas that have not been previously reported, according to a new study.

The new map may ultimately help brain surgeons plan operations. It will also help scientists better understand differences between the brains of typical people and the brains of people with disorders related to brain functioning, such as autism, schizophrenia and dementia, researchers who were not affiliated with the new study said.

In the study, researchers identified a total of 180 areas of the cerebral cortex — the outermost layer of the brain — in each brain hemisphere, said lead study author Matthew Glasser, a neuroscience researcher at Washington University in Saint Louis. Researchers consider an "area" of the brain to be a section of the organ that is dedicated to coordinating a particular set of information from many different signals. [3D Images: Exploring the Human Brain]

The areas identified in the new map include 83 that had previously been identified, along with 97 new areas, Glasser said.

The addition of the 97 new cortical areas shows that "the human cortex is even more complex than we had originally thought," said Ramesh Raghupathi, a neuroscientist at Drexel University's College of Medicine in Philadelphia, who was not involved in the new study.

The map reveals new information even for the areas that had been mapped before, because the original mapping had been done at a much less detailed level, Glasser said.

For example, one area that scientists previously identified and named "area 31" has now been divided into three areas named 31a, 31pd, and 31pv, the researchers said in their study, published today (July 20) in the journal Nature.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The very first map of the human cortex, which identified 50 areas, was created in the first decade of the 20th century by a German neuroanatomist, Korbinian Brodmann. Since then, many other maps of the cortex have identified anywhere from 50 to 200 areas, the researchers said.

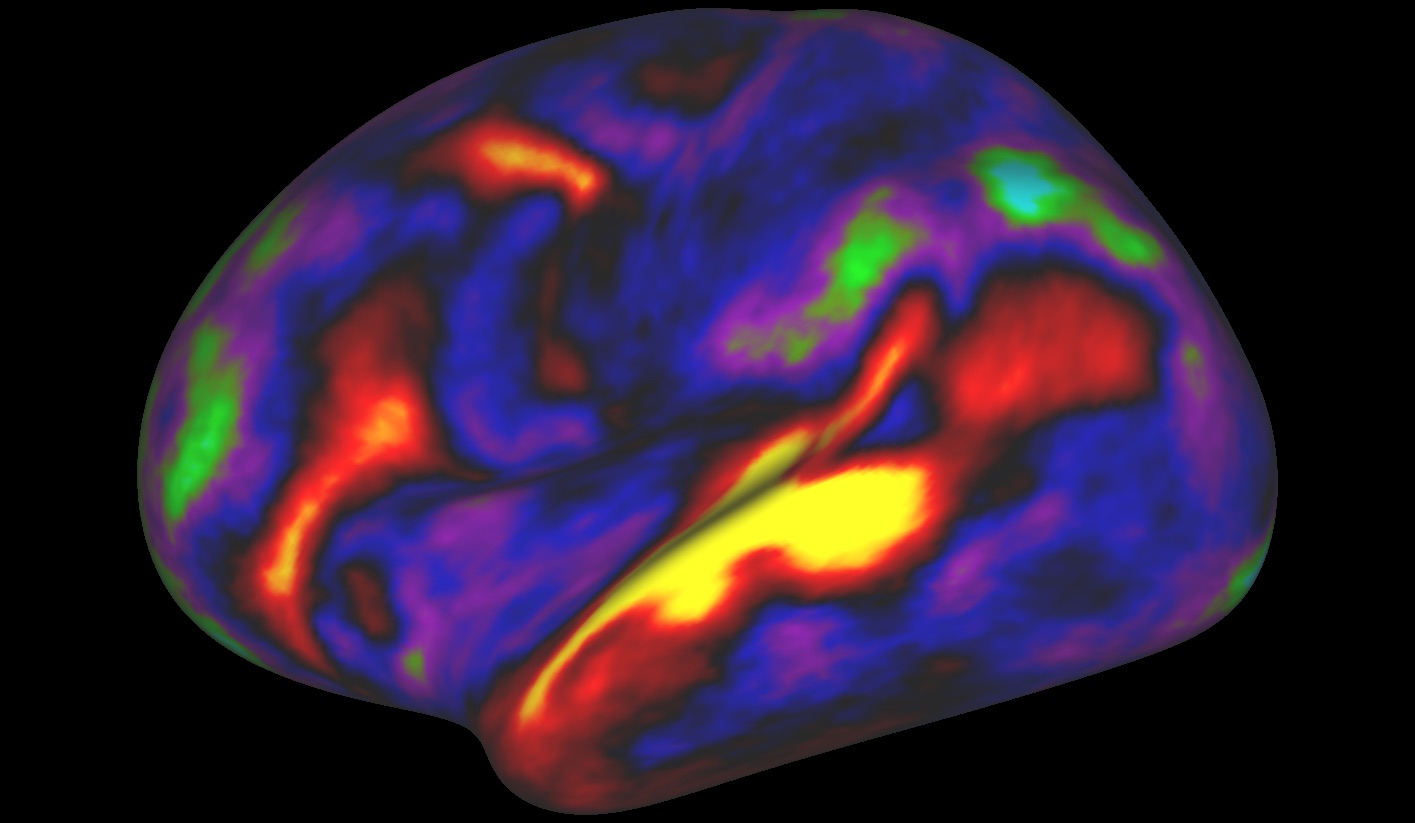

To make the new map, the researchers collected data from brain scans of 210 healthy young adults. The researchers measured, for example, how thick the cortex was in each person. The participants' brains were scanned when they were not doing anything, and again when they were performing simple tasks, such as listening to a story.

The researchers then confirmed the existence of the 180 specific brain areas using brain scans of a second group, consisting of 210 people.

The new map was created based on brain data from a much larger number of people than used to make previous maps, Glasser said. Another difference is that the researchers took into account multiple properties of the brain, such as its structural architecture and function and the thickness of the cortex, Glasser said. Previous maps were typically based on only one of these properties, he said.

Because of these differences, the new map paints a more precise picture of the brain than the previous maps did, the researchers said. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Human Brain]

The new map will allow brain surgeons to better pinpoint where exactly in the brain their patients' health problems stem from, Raghupathi said. "This kind of information is going to be very useful to a neurosurgeon who needs to" stimulate or identify only a small part of the cortex that may be responsible for a patient's language problem or a motor problem, he told Live Science.

"This is an amazing body of work," said Sophie Molholm, a cognitive neuroscientist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, who was not involved in a new study.

This new fine-grained map of the brain could also be used to better understand how brains that have developed without problems may differ from the brains of people with atypical brain development, or who have conditions such as autism and schizophrenia, she said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus