'Dragon Silk' Armor Could Protect US Troops

Genetically modified silkworms that spin special fibers, known as "Dragon Silk," could soon be used to protect soldiers in the U.S. Army, its manufacturer, Kraig Biocraft Laboratories, announced this week.

The U.S. Army recently awarded the Michigan-based company a contract to test its silk products, Kraig Biocraft Laboratories announced on Tuesday (July 12). Researchers at the lab will collect the modified silk and give it to another company. That company will weave it into fabric and then give it to the U.S. Army for testing, the company said.

"Dragon Silk scores very highly in tensile strength and elasticity," which makes is one of the toughest fibers known to man, Jon Rice, the chief operations officer at Kraig Biocraft Laboratories, said in a statement. [7 Technologies That Transformed Warfare]

Despite its mythical name, Dragon Silk is actually the work of genetic engineers. It's widely known, at least in the materials industry, that spider silk has exceptional strength, resilience and flexibility, Rice told Live Science.

"Spider silk is five to 10 times stronger than conventional silkworm silk," Rice said. "It's also, in some cases, as much as twice as elastic. It's even tougher than Kevlar."

However, it isn't possible to set up a one-stop shop for spider silk. Spiders aren't amenable to producing silk in concentrated colonies, largely because many are cannibalistic, he said. So, engineers found DNA within several spiders that is responsible for making silk-related proteins, and inserted it into silkworms.

In 2011, a study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences described the technique, explaining how the researchers removed the silkworms' silk-making proteins and replaced them with the spiders' proteins to create super silkworms — that is, silkworms that can spin composite spider silk.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

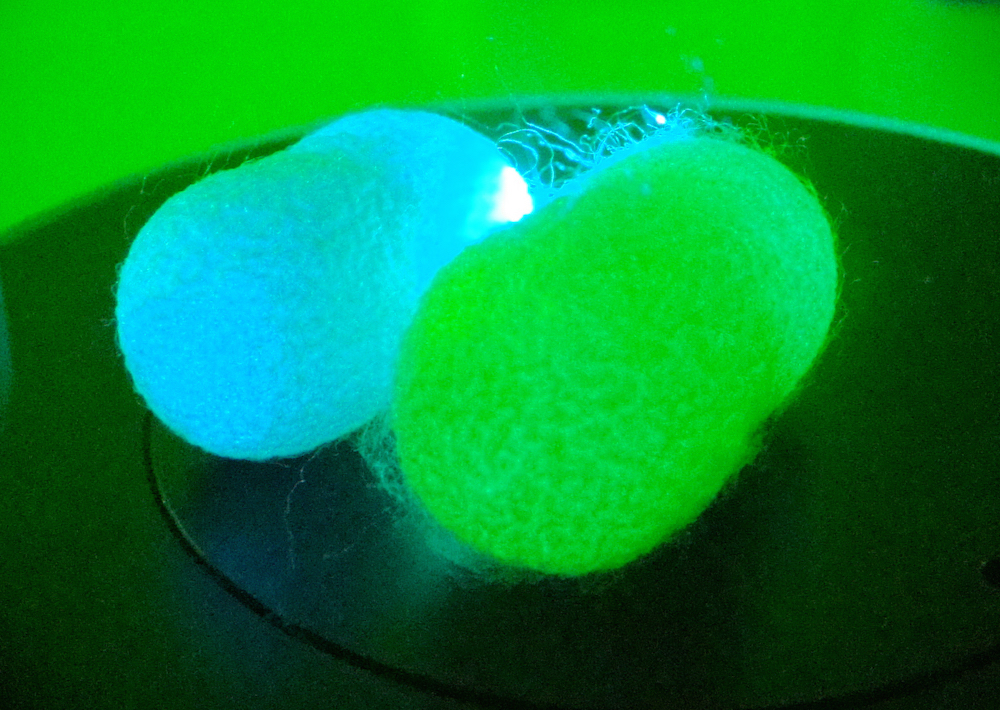

A silkworm has a lifecycle that's similar to any caterpillar's that turns into a moth. Silkworms spin cocoons when they're about 30 to 35 days old, just when they're ready to metamorphose into moths, Rice said. Most of these cocoons are collected by Kraig Biocraft Laboratories, and the company then makes them into silk. But some silkworms are able to reproduce and pass down their newly acquired silky trait to their offspring, Rice said.

The modified silk is about 1,000 times more cost effective than its competitors, Rice added. Modified silk made from complex fermentation processes costs about $30,000 to $40,000 a kilogram (2.2 lbs.), while the lab's silk costs less than $300 for the same amount, Rice said.

If Dragon Silk performs well in the U.S. Army tests, which include ballistic-impact trials, Kraig Biocraft Laboratories could receive a nearly $1 million contract with the military to produce more of the fabric, the company said in the statement.

Still, Rice doesn't want to limit Dragon Silk to military uses. He plans to expand the company's products into the realm of other protective clothing, as well as athletic wear, he said.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus