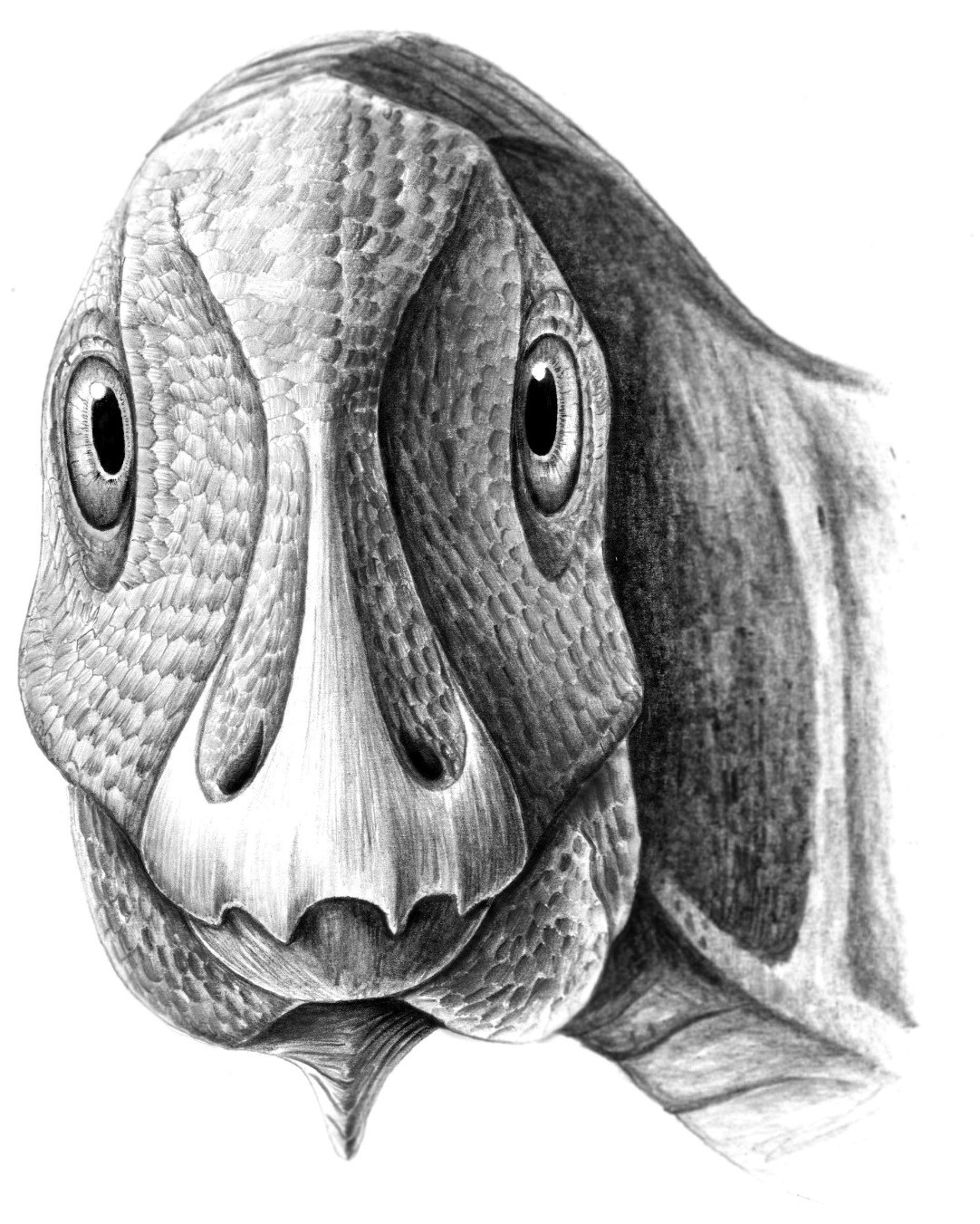

Dwarf Dinosaur Sported Lumpy Tumor on Its Face

During its lifetime about 69 million years ago, a duck-billed dinosaur dwarf walked around with a tumor on its lower jaw, though the unusual growth likely didn't cause any pain, a new study finds.

The same type of noncancerous facial tumor is also found in some modern reptiles and mammals, including humans. But this is the first time researchers have found it in a fossil animal, in this case on Telmatosaurus transsylvanicus, an early duck-billed dinosaur, also known as a hadrosaur, the researchers said. [Photos: Duck-Billed Dinos Found in Alaska]

"This discovery is the first ever described in the fossil record and the first to be thoroughly documented in a dwarf dinosaur," one of the study's co-authors, Kate Acheson, a doctoral student of geology at the University of Southampton in England, said in a statement. "Telmatosaurus is known to be close to the root of the duck-billed dinosaur family tree, and the presence of such a deformity early in their evolution provides us with further evidence that the duck-billed dinosaurs were more prone to tumors than other dinosaurs."

Researchers found the fossils in western Romania in the "Valley of the Dinosaurs," which is part of a World Heritage site honored by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

"It was obvious that the fossil was deformed when it was found more than a decade ago, but what caused the outgrowth remained unclear until now," study co-author Zoltán Csiki-Sava, a paleontologist at the University of Bucharest in Romania, said in the statement.

The team used a micro-computerized tomography (CT) scanner to "peek unintrusively inside the peculiar Telmatosaurus jawbone," Csiki-Sava said. The results showed that the dinosaur had ameloblastoma, a benign, noncancerous growth that affects the jaws.

"The discovery of an ameloblastoma in a duck-billed dinosaur documents that we have more in common with dinosaurs than previously realized," said study co-author Dr. Bruce Rothschild, a professor of medicine at Northeast Ohio Medical University and an expert in paleopathology (the study of ancient diseases).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Humans usually don't feel any serious pain from a developing ameloblastoma, and the dinosaur likely didn't either, the researchers said. But the animal wasn't full-grown when it died, so it's possible that the tumor somehow contributed to the dinosaur's death, they said.

The researchers found only the animal's two lower jaws, so it's difficult to pinpoint how the dinosaur died without examining the rest of its bones, the researchers said. Perhaps the tumor made the dinosaur look different or "even slightly disabled by a disease," which could have made it a target for predators hunting for susceptible prey within the duck-billed dinosaur herd, Csiki-Sava said.

Finding evidence of tumors on dinosaur bones is rare, but not unheard of. Researchers previously found two tumors on an individual titanosaur, a long-necked, long-tailed herbivorous giant, and on the duck-billed dinosaurs Brachylophosaurus, Gilmoreosaurus, Bactrosaurus and Edmontosaurus, as well as the carnivorous, Jurassic-age Dilophosaurus wetherilli. These tumors, however, were not located on the dinosaurs' faces.

The study was published online today (July 5) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus