Editor's Note: This article was updated at 3:50 p.m. E.T. on Thursday June 23

The grave of a woman with a bizarre, long-headed skull has been unearthed in Korea.

The woman was part of the ancient Silla culture, which ruled much of the Korean peninsula for nearly a millennium.

Unlike some of the deformed, pointy skulls that have been found throughout the world in other ancient graves, however, it is unlikely that this woman had her head deliberately flattened, the researchers said. [See Images of the Long-Headed Woman's Facial Reconstruction]

Ancient culture

The ancient Silla Kingdom reigned over part of the Korean Peninsula from 57 B.C. to A.D. 935, making it one of the longest-ruling royal dynasties. Many of Korea's modern-day cultural practices stem from this historic culture. Yet despite its long reign and wide-ranging influence on culture, the number of Silla burials with intact skeletons remained few and far between, said study co-author Dong Hoon Shin, a bioanthropologist at Seoul National University College of Medicine in the Republic of Korea.

"The skeletons are not preserved well in the soil of Korea," Shin told Live Science in an email. [7 Strange Facts About North Korea]

However, in 2013, researchers had a lucky break while excavating a grave near Gyeongju, the historic capital of the Silla Kingdom. Inside a traditional burial coffin, called a "mokgwakmyo," lay the nearly perfectly intact bones of a woman who died in her late 30s.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Long head

The team managed to extract the woman's mitochondrial DNA, or DNA that is passed from mother to daughter. The analysis revealed that she belonged to a genetic lineage that is present, though not common, in East Asia today. Analysis of the carbon isotopes (versions of carbon with different weights) in the skeleton also revealed that the woman was likely a strict vegetarian, in keeping with the interpretation of Buddhism that was prevalent at the time in the country. She also ate a greater percentage of her calories from foods with a type of carbon found in foods such as rice, wheat and potatoes, versus millet or maize, the researchers reported June 1 in the journal PLOS ONE. (The carbon isotope testing cannot determine whether the diet was composed primarily of rice, potatoes or wheat.)

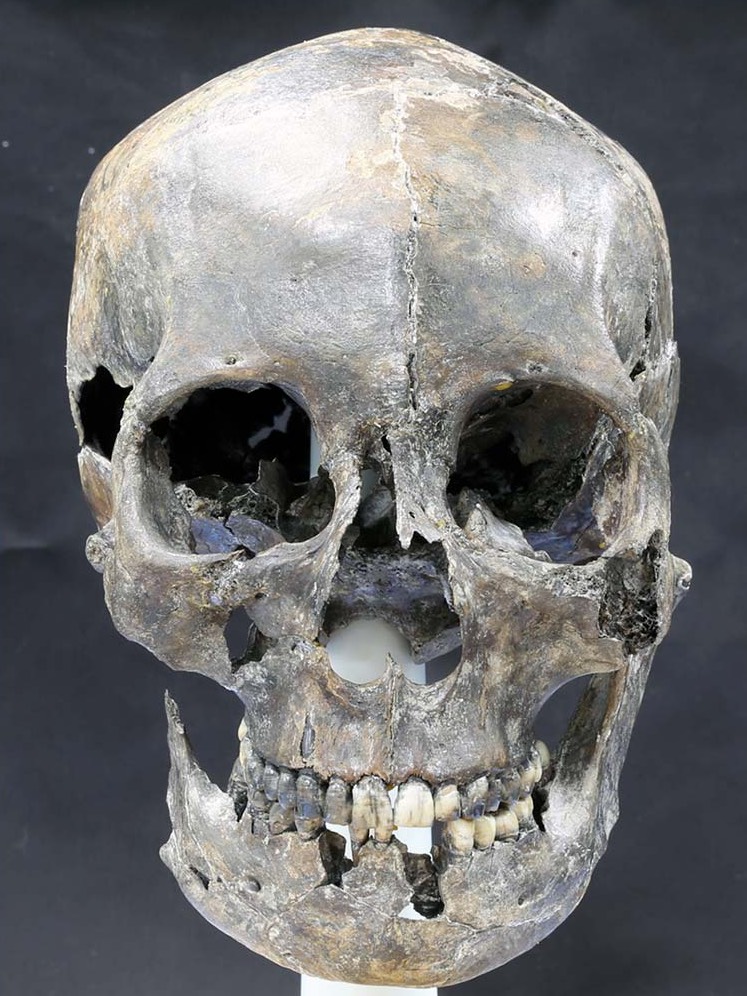

The team was also able to reconstruct her facial features and head shape based on skull fragments. It turned out that the woman was dolichocephalic, meaning her head width was less than about 75 percent of its length.

That differs somewhat from the trends in the region today, where people are more commonly brachycephalic, meaning their head width is at least 80 percent of the head length.

One possibility is that the head was deliberately deformed to have this elongated shape. Skull deformation has occurred throughout the world, and in fact, archaeologists have unearthed evidence of skull deformation from the neighboring Gaya Kingdom, said study co-author Eun Jin Woo, a physical anthropologist at Seoul National University in the Republic of Korea.

However, the team ultimately ruled out this explanation because heads that are deliberately deformed usually have flatter bones in the front of the skull. To compensate for all of the pressure that head deformation causes, the bones in the side of the skull tend to grow more, Woo said.

"The skull in this study did not show the shape changes in deformed crania," Woo told Live Science in an email. "In this regard, we think her head should be considered as normal variation in the group."

Editor's Note: This article was updated to clarify that foods such as rice, potatoes and wheat produce the same carbon signature, so researchers cannot distinguish which of those specific foods made up the bulk of the Silla woman's diet.

Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus