T. Rex Was Pregnant, Bone Test Confirms

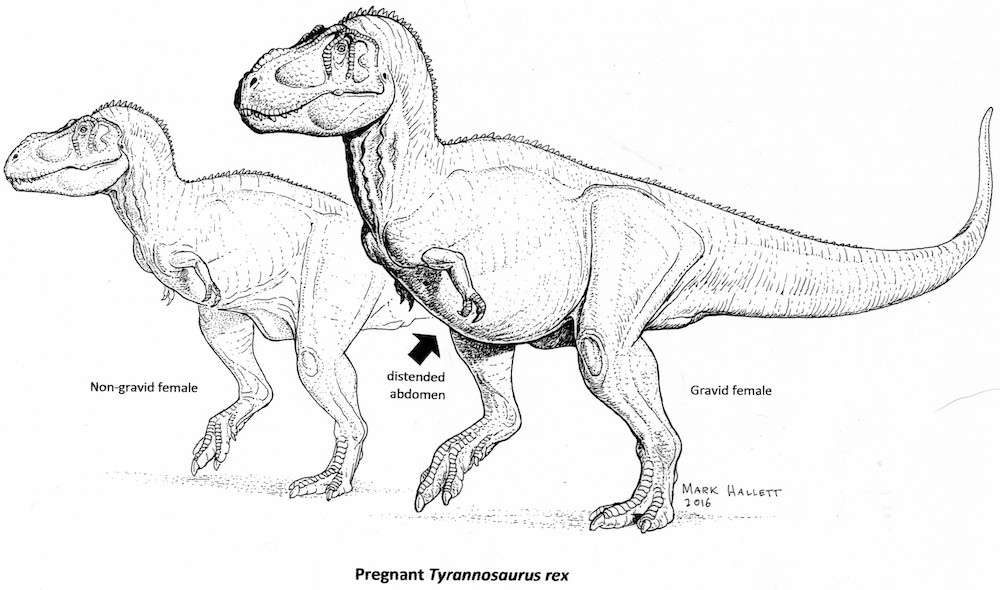

About 68 million years ago, a pregnant Tyrannosaurus rex died in ancient Montana. Her remains might provide clues about how to identify male and female theropods, or bipedal meat-eating dinosaurs, a new study finds.

The finding is an exciting one — researchers verified that the T. rex was pregnant by looking at the organic components in the dinosaur's bone structure, elements that had survived for tens of millions of years since the predator's death, said study lead researcher Mary Schweitzer, an evolutionary biologist at North Carolina State University.

"We need to quit selling fossils short," Schweitzer told Live Science. "They have a lot more information in them than we would think of [finding in] 65-million-year-old bone." [Image Gallery: The Life of T. Rex]

A paleontologist discovered the T. rex in Hell Creek Formation in 2000. Bob Harmon, of the Museum of the Rockies in Montana, sat down in dinosaur territory one day, and unexpectedly felt a fossil behind his back, Schweitzer said. Harmon shared the good news with his colleagues, and they spent the next three years excavating the enormous specimen.

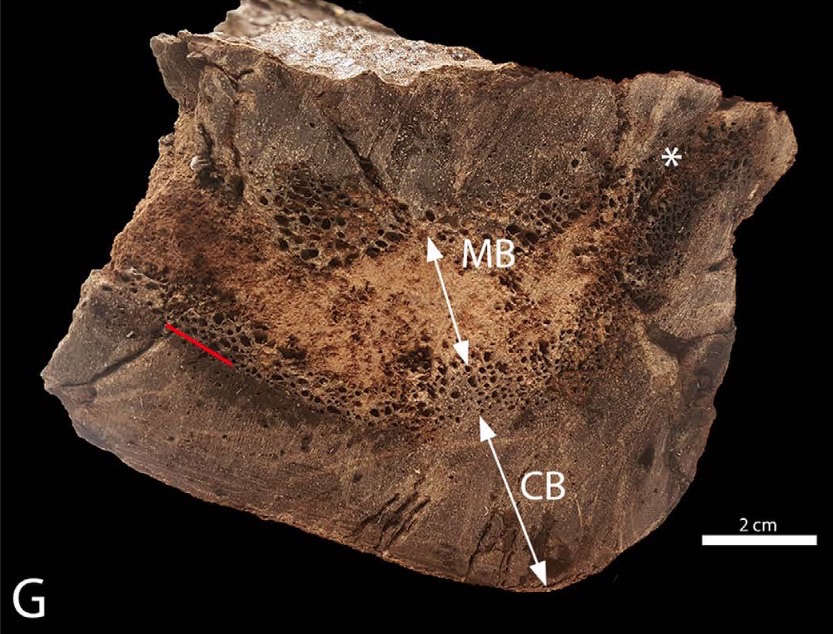

Afterward, the paleontologists gave the femur, a leg bone, to Schweitzer, who, along with her colleagues, examined the microscopic features of the fossil. In 2005, the team published a study in the journal Science announcing that the fossil contained medullary bone, which is a type of bone with extra calcium deposits that help female egg-laying creatures, such as birds, lay eggs. Medullary bone is present only just before or during the egg-laying process, so its occurrence suggested the T. rex was pregnant, Schweitzer said.

But recently, Schweitzer found herself wondering whether the finding was accurate. New technologies and information had come to light in the intervening years. Schweitzer wondered if she did the experiment again, whether she would still get the same results and find that the dinosaur was pregnant, she said.

"I think good scientists should always be second-guessing themselves," Schweitzer said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

So, she decided to check the chemistry of the T. rex's femur. Such a test would show whether the fossil had medullary bone, or whether it actually had osteopetrosis, a condition that makes bones unusually dense. Under the microscope, medullary bone and bone with osteopetrosis look remarkably similar, Schweitzer said.

However, the two are chemically different. Medullary bone contains the organic compound keratan sulfate, and bone with osteopetrosis does not. Schweitzer and her colleagues tested for the compound using different chemicals, including monoclonal antibodies (immune cells that bind only to a specific agent — in this case, keratan sulfate). The researchers found that the ancient bone still contained some keratan sulfate.

The researchers also used the antibodies to analyze medullary bone from an ostrich and chicken. The results confirmed those from the 2005 study, that the T. rex had medullary bone and was likely pregnant when she died, Schweitzer said.

"This analysis allows us to determine the gender of this fossil, and gives us a window into the evolution of egg laying in modern birds," Schweitzer said in a statement.

Because medullary bone is present only in females during egg-laying periods, it's relatively rare in fossils. Even when present, it can be difficult to identify without cutting off a sample of dinosaur bone and examining it under a microscope or with a chemical test. But the researchers found that doing an initial computed tomography (CT) scan of dinosaur bone can help determine whether a fossil is worth investigating, Schweitzer said. [Gallery: Photos of Tiny Dinosaur Embryos]

This technique could help researchers find more medullary bone, said study co-author Lindsay Zanno, a paleontologist at North Carolina State University. Moreover, once the presence of medullary bone confirms that a dinosaur is a female, researchers can look for other clues that might help determine whether it's a boy or a girl dinosaur.

"It's a dirty secret, but we know next to nothing about sex-linked traits in extinct dinosaurs. Dinosaurs weren't shy about sexual signaling, all those bells and whistles, horns, crests, and frills, and yet we just haven't had a reliable way to tell males from females," Zanno said in the statement. "Just being able to identify a dinosaur definitively as a female opens up a whole new world of possibilities. Now that we can show pregnant dinosaurs have a chemical fingerprint, we need a concerted effort to find more [medullary bone]."

This T. rex isn't the first known example of a pregnant dinosaur. Fossils of both Allosaurus (a Jurassic-period, meat-eating relative of T. rex) and Tenontosaurus (a herbivorous relative of the duck-billed dinosaur) have been found with medullary bone, suggesting that the individuals may have died just before, during or after laying eggs.

The new study was published online today (March 15) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.