Will the World's Largest Supercollider Spawn a Black Hole? (Op-Ed)

Don Lincoln is a senior scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy's Fermilab, the United States' biggest Large Hadron Collider research institution. He also writes about science for the public, including his recent "The Large Hadron Collider: The Extraordinary Story of the Higgs Boson and Other Things That Will Blow Your Mind" (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014). You can follow him on Facebook. The opinions here are his own. Lincoln contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Cutting-edge science is an exploration of the unknown; an intellectual step into the frontier of human knowledge. Such studies provide great excitement for those of us passionate about understanding the world around us, but some are apprehensive of the unknown and wonder if new and powerful science, and the facilities where it is explored, could be dangerous. Some even go so far as to ask whether one of humanity's most ambitious research projects could even pose an existential threat to the Earth itself. So let's ask that question now and get it out of the way.

Can a supercollider end life on Earth? No. Of course not.

But it's not really a silly question for people who haven't thought carefully about it. After all, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world's biggest and most powerful particle accelerator, is explicitly an instrument of exploration, one that is designed to push back the frontiers of ignorance. It's not so unreasonable to ask how you know something isn't dangerous if you've never done it before. So how is it I can say with such utter confidence that the LHC is completely safe?

Well, the short answer is that cosmic rays from space constantly pummel the Earth with energies that dwarf those of the LHC. Given that the Earth is still here, there can be no danger, or so the reasoning goes.

And that could well be the final story, but the tale is much richer than that short (but very accurate) answer would lead you to believe. So let's dig a bit deeper into what makes some suspect a danger, and then explore a fairly detailed description of the point and counterpoint involved in delivering a solid and satisfying answer to the question.

Can the LHC create an Earth-killer black hole?

Skeptics have proposed that the LHC would produce many possible dangers, ranging from the vague fear of the unknown to some that are strangely specific.

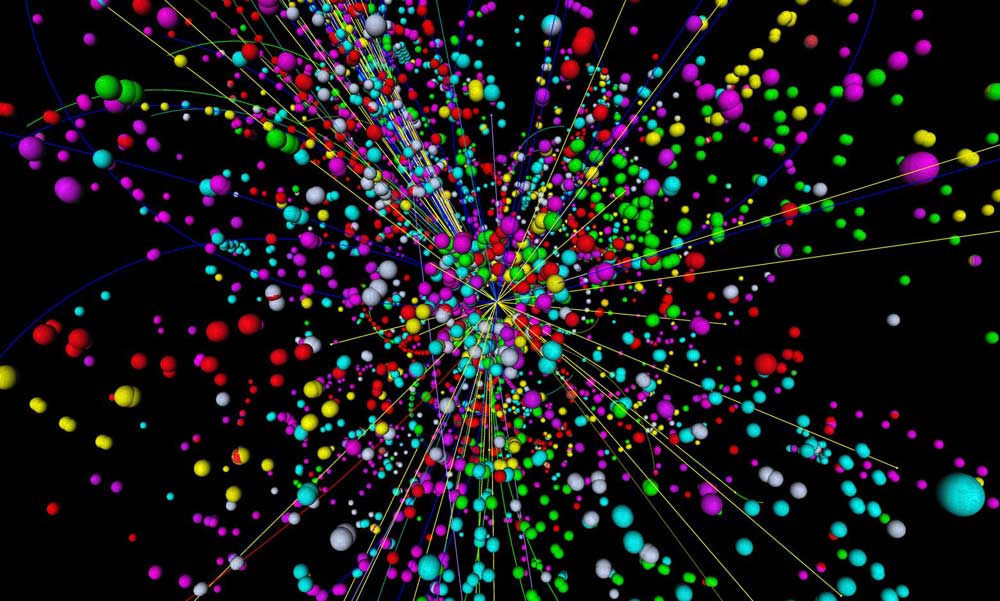

The most commonly mentioned is the idea that the LHC can make a black hole. In popular literature, black holes are ravening monstrosities of the universe, gobbling up everything around them. Given such a depiction, it's not at all unreasonable for people to then wonder if a black hole created by the LHC might reach out and destroy the accelerator, the laboratory, then Switzerland, Europe and finally the Earth. This would be a scary scenario, were it credible — but it's not.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What immediately follows are the weaker (but still compelling) reasons why this possibility is, well, not possible, and in the next section you will see the cast-iron and gold-plated reasons to dismiss this and all other possible Earth-ending scenarios.

The first question is whether a black hole can even be created at the LHC. Alas, when looking at all of the scientific evidence and using our most modern understanding of the laws of the universe, there is no way that the LHC can make a black hole. Gravity is simply too weak for this to occur.

Some skeptics protest that one explanation for the weakness of gravity is that tiny extra dimensions of space exist. According to that theory, gravity is really strong and just appears to be weak because gravity can "leak" into the extra dimensions. Once we start probing those tiny dimensions, the strong gravity could perhaps make a black hole. Sadly for black hole aficionados, no one has found evidence for the existence of extra dimensions, and if they don't exist, the LHC can't make black holes.

So the entire underlying idea of that particular possible danger is built on a long shot. Yet, even in the unlikely case that extra dimensions are real and a black hole can be created, there is a good reason to not worry about black holes damaging the Earth.

The shield against that hypothetical danger is Hawking radiation. Proposed in 1974 by Steven Hawking, Hawking radiation is essentially the evaporation of a black hole caused by its interactions with particles created in the vicinity of the hole. While black holes will absorb surrounding material and grow, an isolated black hole will slowly lose mass.

The mechanism is a quantum mechanical one, involving pairs of particles being made near the surface of the hole. One particle will go into the hole, but the other will escape and carry away energy. Since, according to Einstein's theory of general relativity, energy and mass are the same, this process has the effect of very slowly decreasing the mass of the black hole. Even though one particle enters the hole, the loss of the other results in the hole slowly evaporating. This is a tricky point. Most people think of a black hole as the mass at the center, but it's actually both the mass at the center and the energy stored in the gravitational field. The particle zooming down to the center is just moving around in the black hole, while the particle that moves out escapes the black hole entirely. Both the mass of the escaping particle and the energy it carries are lost to the black hole, reducing the energy of the entire black hole system.

And the rate at which a hole evaporates is a strong function of the hole's size. A large black hole will lose energy very slowly, but a small one will evaporate in the blink of an eye. In fact, any black hole the LHC could possibly make, via any possible theory, will disappear before it can get near any other matter to gobble up.

Strange strangelets

Another proposed danger is a thing called a strangelet. A strangelet is a hypothetical subatomic particle composed of roughly an equal number of up, down and strange quarks.

Mind you, there is zero evidence that strangelets are anything other than an idea born in the fertile imagination of a theoretical physicist. But, if they exist, the claim is that a strangelet is essentially a catalyst. If it impacts ordinary matter, it will make the matter it touches also turn into a strangelet. Following the idea to its logical conclusion, if a strangelet were made on Earth, it would result in the entire planet collapsing down into a ball of matter made of strangelets … kind of like turning the Earth into an exotic version of neutron star. Essentially a strangelet can be thought of as a subatomic zombie; one that turns everything it touches into a fellow strangelet zombie.

But there is no evidence that strangelets are real, so that might be enough to keep some people from worrying. However, it's still true that the LHC is a machine of discovery and maybe it could actually make a strangelet … well, if they really exist. After all, strangelets haven't been definitively ruled out and some theories favor them. However, an earlier particle accelerator called the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider went looking for them and came up empty.

Those are but two ideas for how a supercollider could pose a threat, and there are more. We could list all of the possible dangers, but there remains something more unsettling to keep in mind: Since we don't know what happens to matter when we start studying it at energies only possible with the LHC (that is, of course, the point of building the accelerator), maybe something will happen that was never predicted. And, given our ignorance, maybe that unexpected phenomenon might be dangerous.

And it is that last worry that could have potentially been so troubling to the LHC's creators. When you don't know what you don't know, you … well … you don't know. Such a question requires a powerful and definitive answer. And here it is…

Why the LHC is totally safe

Given the exploratory nature of the LHC research program, what is needed is an ironclad reason that demonstrates that the facility is safe even if no one knows what the LHC might encounter.

Luckily, we have the most compelling answer of all: Nature has been running the equivalent of countless LHC experiments since the universe began — and still does, every day, on Earth.

Space is a violent place, with stars throwing off literally tons of material every second — and that's the tamest of phenomena. Supernovas occur, blasting star stuff across the cosmos. Neutron stars can use intense magnetic fields to accelerate particles from one side of the universe to another. Pairs of orbiting black holes can merge, shaking the very fabric of space itself.

All of those phenomena, as well as many others, cause subatomic particles to be flung across space. Mostly consisting of protons, those particles travel the lengths of the universe, stopping only when an inconvenient bit of matter gets in their way.

And, occasionally, that inconvenient bit of matter is the Earth. We call these intergalactic bullets — mostly high-energy protons — "cosmic rays." Cosmic rays carry a range of energies, from the almost negligible, to energies that absolutely dwarf those of the LHC.

To give a sense of scale, the LHC collides particles together with a total energy of 13 trillion (or tera) electron volts of energy (TeV). The highest-energy cosmic ray ever recorded was an unfathomable 300,000,000 TeV of energy.

Now, cosmic rays of that prodigious energy are very rare. The energy of more common cosmic rays is much lower. But here's the point: Cosmic rays of the energy of a single LHC beam hit the Earth about half a quadrillion times per second. No collider necessary.

Remember that cosmic rays are mostly protons. That's because almost all of the matter in the universe is hydrogen, which consists of a single proton and a single electron. When they hit the Earth's atmosphere, they collide with nitrogen or oxygen or other atoms, which are composed of protons and neutrons. Accordingly, cosmic rays hitting the Earth are just two protons slamming together — this is exactly what is happening inside the LHC. Two protons slamming together.

Thus, the barrage of cosmic rays from space have been doing the equivalent of LHC research since the Earth began — we just haven't had the luxury of being able to watch.

Now one must be careful. It's easy to throw numbers around a bit glibly. While there are lots of cosmic rays hitting the atmosphere with LHC energies, the situations between what happens inside the LHC and what happens with cosmic rays everywhere on Earth are a bit different.

Cosmic ray collisions involve fast-moving protons hitting stationary ones, while LHC collisions involve two beams of fast-moving protons hitting head-on. Head-on collisions are intrinsically more violent; so to make a fair comparison, we need to consider cosmic rays that are much higher in energy, specifically about 100,000 times higher than LHC energies.

Cosmic rays of that energy are rarer than the lower energy ones, but still 500,000,000 of them hit the Earth's atmosphere every year.

When you remember that the Earth is 4.5 billion years old, you realize that the Earth has experienced something like 2 billion billion cosmic ray collisions with LHC-equivalent energies (or higher) in the atmosphere since the Earth formed. In order to make that many collisions, we'd need to run the LHC continuously for 70 years. Given that we're still here, we can conclude that we're safe.

But to be absolutely sure ...

The cosmic ray argument is fantastic, as it is independent of any possible LHC danger, including ones we haven't imagined yet. However, there is a loophole that potentially reduces the argument's strength. Because cosmic ray collisions are between a fast-moving and a stationary proton, the "dangerous" particle (whatever that might be) gets produced at high velocity and may shoot out of the Earth before it has time to damage it. (It's like in billiards when a cue ball hits another ball. After the impact, at least one, and often both, go flying.) In contrast, the LHC beams hit head-on, making stationary objects. (Think of two identical cars with identical speeds hitting head-on.) Maybe they will stick around and wreak carnage on the globe.

But there is an answer to that too. I picked the Earth because it is near and dear to us, but the Earth isn't the only thing being hit by cosmic rays. The sun gets hit as well; and when a cosmic ray hits the sun, it might make a high-energy "dangerous" product, but that product then has to travel through a much larger amount of matter. And this doesn't take into account that the sun is much larger than the Earth, so it experiences many more high-energy collisions than our planet does.

Further, we can expand the number of cosmic targets to include neutron stars, which consist of matter so dense that whatever potentially dangerous thing we might consider will stop dead in the neutron star right after it is made. And yet the sun and the neutron stars we see in the universe all are still there. They haven't disappeared.

Safety assured!

So that argument is the bottom line. When you ask if the LHC is safe, you have to realize that the universe has already done the experiments for us.

Cosmic rays hit the Earth, the sun, other stars and all the myriad denizens of the universe with energies that far exceed those of the LHC. This happens all the time. If there were any danger, we would see some of these objects disappearing before our eyes. And yet we don't. Thus, we can conclude that whatever happens in the LHC, it poses exactly, precisely, inarguably, zero danger. And you can't forget the crucial point that this argument works for all conceivable dangers, including those that nobody has imagined yet.

So having established the ironclad safety of the LHC, what then? Well, we absolutely hope that we do make black holes in the LHC — as explained, they would be tiny and not gobble up the planet. If we do see tiny black holes, we'll have figured out why gravity seems so weak. We'll probably have established that extra dimensions of space exist. We'll be that much closer to finding a theory of everything, a theory that is so persuasive, simple and concise that we can write its equation on a T-shirt.

While we are now assured that the LHC is utterly safe, it is absolutely true that the safety question was important for scientists to investigate. In fact, the whole exercise was a satisfying one, as it used the best scientific principles to come to a definitive conclusion that all can agree is valid. So now we can push back the boundaries of our ignorance, with only our increasing excitement of the prospect of a discovery to distract us.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.