Photos: Catch a Glimpse of the Reclusive Glowing Green Eel

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

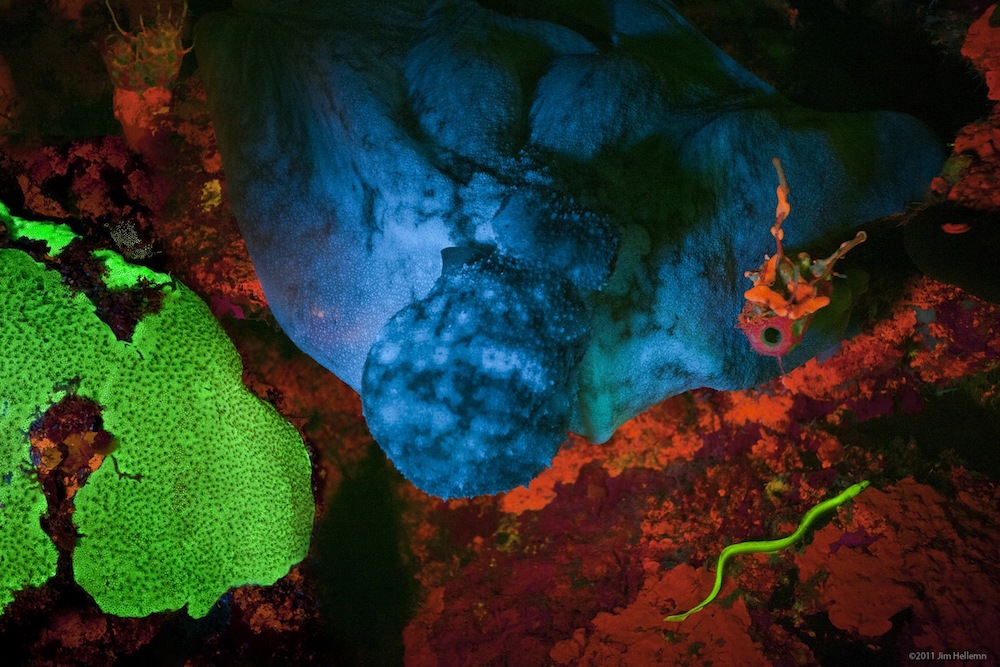

A serendipitous photo taken during a scuba-diving trip in the Caribbean clued researchers into the world of a mysterious green and glowing eel. Though the green eel species is known for being shy and reclusive, divers managed to catch two and examine their glowing properties. An analysis showed that the eels have a completely newfound class of fluorescent protein that needs bilirubin to glow. These proteins likely helped shape the eels' evolution, and may help researchers develop new techniques in the lab. [Read the Full Story on the Glowing Green Eel]

Serendipitious photo

This biofluorescent green eel (lower right corner) surprised scuba-diving scientists, and prompted them to study its glowing proteins. (Image credit: Copyright Jim Hellemn)

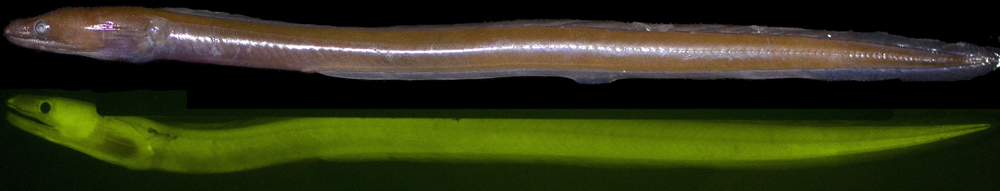

Green science

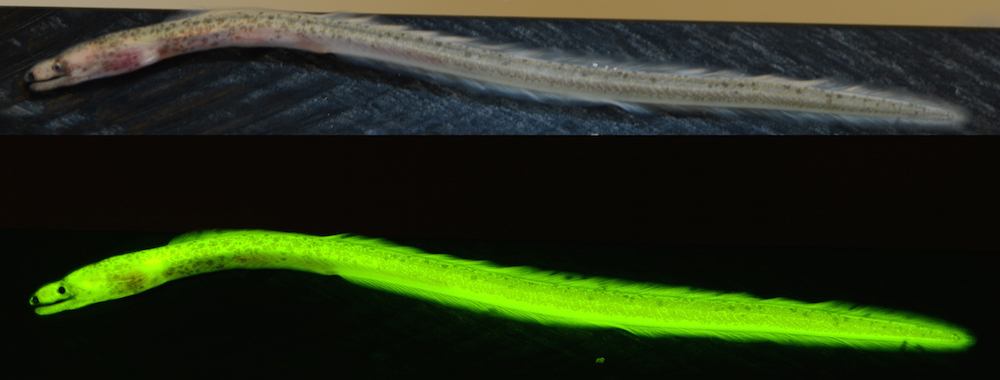

The green eel Kaupichthys hyoproroides that was collected in the Bahamas. Typically, researchers collect dozens if not hundreds of specimens for research, but the scientists on this study decided to collect just two.

"We're trying to be as non-invasive as possible when we do sample," said study lead researcher David Gruber, an associate professor of biology at Baruch College in New York City. (Image credit: Copyright David Gruber, John Sparks and Vincent Pieribone)

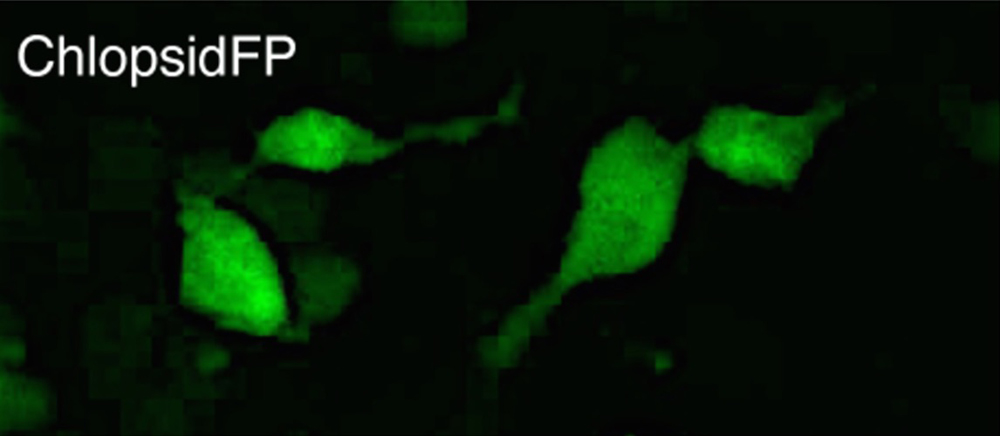

Fluorescent protein

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new eel fluorescent protein expressed in a human cell line. The protein needs bilirubin to glow, the researchers found. (Image credit: Vincent Pieribone)

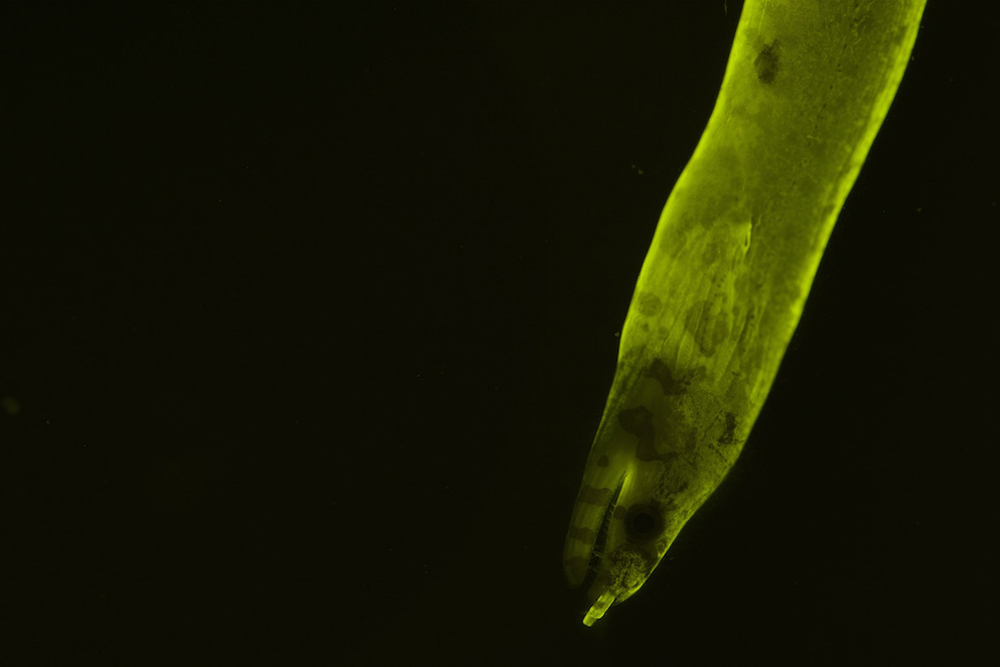

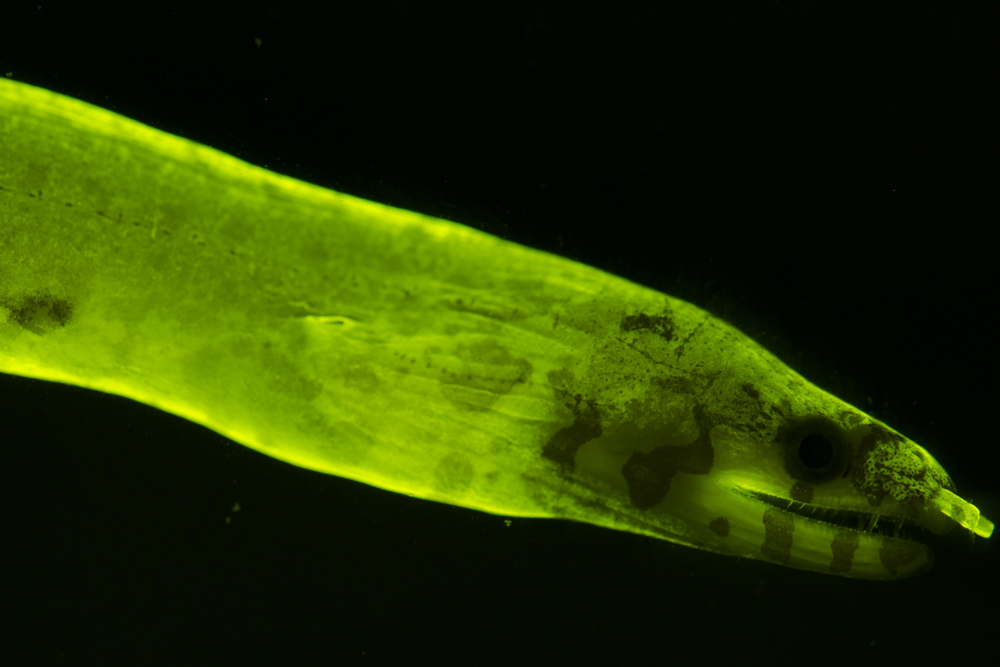

Close up

A close up photo of the glowing eel. (Image credit: Copyright John Sparks, Vincent Pieribone and David Gruber)

Aglow in the dark

In the past few years, researchers have realized that fluorescence is more widespread in marine life than previously realized. These animals biofluoresce by absorbing the blue light available in the ocean and reemitting it at a longer, lower energy wavelength, such as orange, red or, in this case, green. (Image credit: Copyright John Sparks, Vincent Pieribone, David Gruber)

Glowing creature

It's not yet clear why some marine animals fluoresce, but it could be used for mating, predator avoidance and prey attraction. Researchers can also use the fluorescent proteins in biomedical experiments, such as observing chatter between nerve cells in the brain. (Image credit: Copyright John Sparks, Vincent Pieribone and David Gruber)

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus