Artificial Skin Could Give People with Prosthetics a Sense of Touch

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

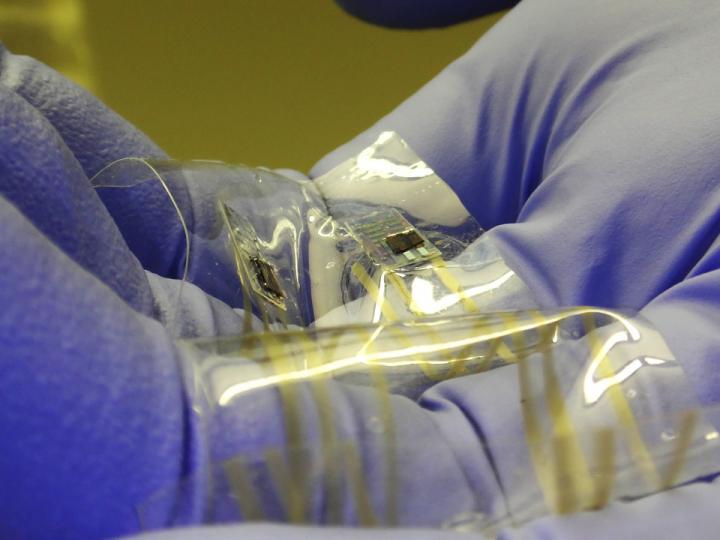

Artificial skin created in a lab can "feel" similar to the way a fingertip senses pressure, and could one day let people feel sensation in their prosthetic limbs, researchers say.

The researchers were able to send the touching sensation as an electric pulse to the relevant "touch" brain cells in mice, the researchers noted in their new study.

The stretchy, flexible skin is made of a synthetic rubber that has been designed, to have micron-scale pyramid like structures that make it especially sensitive to pressure, sort of like mini internal mattress springs. The scientists sprinkled the pressure-sensitive rubber with carbon nanotubes— microscopic cylinders of carbon that are highly conductive to electricity — so that, when the material was touched, a series of pulses is generated from the sensor.

The series of pulses is then sent to brain cells in a way that resembles how touch receptors in human skin send sensations to the brain. "We were able to create [a system] very similar to biological mechanical receptors," said Benjamin Tee, lead author of the paper and a scientist at the Agency for Science, Technology and Research in Singapore. [Bionic Humans: Top 10 Technologies]

To test whether the skin could create electric pulses that brain cells could respond to, the scientists connected the synthetic skin to a circuit connected to a blue LED light. When the skin was touched, the sensor sent electric pulses to the LED which pulsed in response. The sensors translated that pressure pulse into an electric pulses. When the sensors in the skin sent the electrical pulse to the LED — akin to touch receptors in real-life skin sending touch-sensation signals to the brain — a blue light flashed. The higher the pressure, the faster the LED flashed.

Scientists added channelrhodopsin, a special protein that causes brain cells to react to blue light, to the mouse brain cells. The channelrhodopsin let the LED light act like receptor cells in the skin. When the light flashed it sent a signal to the brain cells that the artificial skin had been touched.

The experiment showed that, when the artificial skin was touched, the brain cells would react in the same way as brains react to real skin being touched, the researchers said in the study, published Oct. 16 in the journal Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Using light to stimulate brain cells is a fairly recent area of study called optogenetics, in which scientists add special proteins to brain cells that let them react to light and shows scientists how different parts of the brain work. The advantage of using optogenetics over other technologies that directly stimulate neurons, such as electrodes directly attached to brain tissue, is that higher frequencies can be used, Lee said. Having a technology that can stimulate the cells at higher frequencies is important because it more accurately recreates the way that receptor cells send signals to our brains.

The testing is still in the early phases, and the skin hasn't been tested with human neurons.

"We actually did connect [the sensors] to a robotic hand and a computer," Tee said, adding that they were able to record the pulse spikes. However, these experiments were designed primarily to prove that the technology was able to send a signal that could be registered by the same robotics technologies used in advanced prosthetic technologies, Tee told Live Science.

"The natural next step would be to test [the skin] in higher primates," Tee said. "The eventual goal is to have the skin stimulate real human brains."

Follow Elizabeth Newbern @liznewbern. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus