The 6 most gruesome grave robberies

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The grave is supposed to be a final resting place. Sometimes, though, the postmortem peace is shattered and a corpse disturbed. Graves have been robbed for reasons ranging from ransom to cannibalism, though the most common reason throughout history has probably been the profit motive. Throughout the 1800s, body snatchers in the United States and England sold corpses to anatomists for medical dissections. The practitioners of this unsavory art came to be known as "resurrectionists."

Read on for six of the most gruesome and notorious episodes of body snatching in history.

Victim of body snatchers

U.S. Rep. John Scott Harrison was the son of President William Henry Harrison and the father of President Benjamin Harrison. He was also, despite his political prestige, the victim of body snatchers.

According to a 1950 article in the Ohio History Journal, John Scott Harrison died and was buried in the family plot in North Bend, Ohio, in 1878. Body snatching was a problem at the time; doctors craved corpses for anatomy lessons, and it was not yet legal to use unclaimed bodies for dissection in Ohio. (Today, voluntary body-donation programs allow medical students to learn anatomical lessons from corpses.) To protect Harrison's body, his family interred him in a heavy vault and covered the vault with soil mixed with large rocks. [Bones with Names: Long-Dead Bodies Archaeologists Have Identified]

But that didn't deter the resurrectionists. On the day of Harrison's funeral, mourners noticed that a nearby fresh grave that had contained the body of a man named Augustus Devin was empty. One of Harrison's sons was a friend of Devin's; he joined with a second friend and headed to Cincinnati's medical schools in search of the body.

Instead, they found John Scott Harrison, hanging nude from a rope in a dark chute. Harrison's body had been snatched, too.

"Naturally, this shocking episode created a sensation," reported the Ohio History Journal.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Devin's body was later found preserved in a vat of brine at the University of Michigan medical college.

Charlie Chaplin's ransom

Silent film icon Charlie Chaplin died in December 1977. Several months later, in March 1978, his grave was found open, a pile of fresh earth piled next to the hole.

According to a contemporary report by the Associated Press, Chaplin's entire coffin was missing, and drag marks in the grass suggested it had been dragged to a nearby alley and whisked away by truck. At first, there was no hint as to who had stolen the famed body. Some speculated that crazy fans had stolen the body to repatriate it to Chaplin's native England.

It took more than two months to discover the body snatchers — a Bulgarian and a Polish immigrant who demanded a ransom of 332,000 British pounds — equivalent to approximately 1.7 million British pounds today, or $2.6 million.

Chaplin's widow had no interest in paying the ransom. A police spokesman told The Glasgow Herald: "For her, her husband was in heaven and in her heart, and nowhere else." But she led the body snatchers on so that police could monitor their calls demanding ransom. They eventually nabbed one of the co-conspirators in a phone booth in Lausanne, Switzerland, according to the Herald. Chaplin's body was found buried in a cornfield 12 miles (19 kilometers) from the cemetery. He was reburied in the same grave — but with the addition of a concrete tomb around the casket.

Missing body of 19th-century tycoon

The people who stole the body of 19th-century tycoon Alexander Turney Stewart had better luck with their ransom scheme. Stewart was a rags-to-riches story: An Irish immigrant, he established a dry-goods empire and became one of the richest men in history.

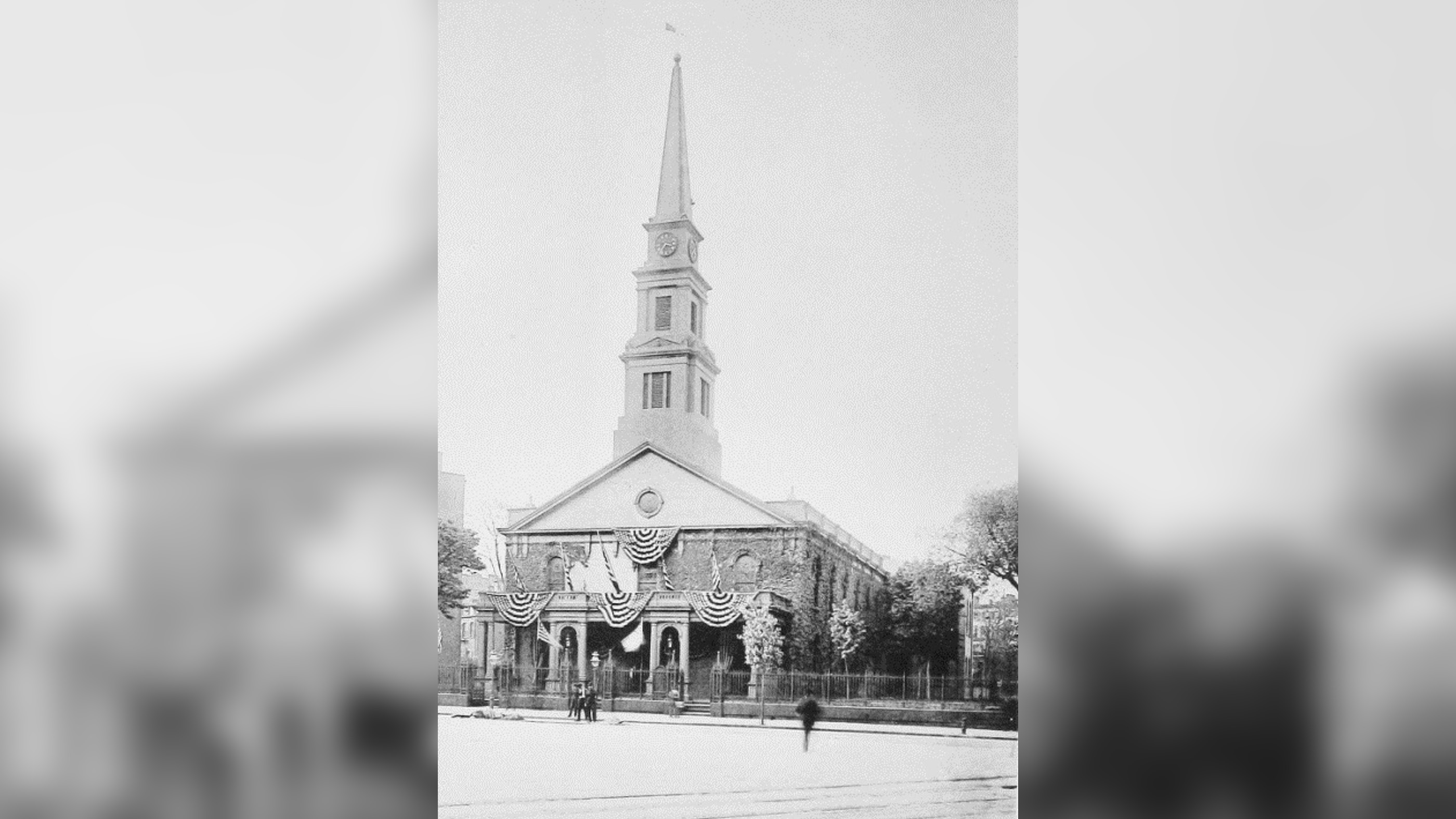

About two years after his death in 1876, Stewart's body vanished from his grave at St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery in New York City. The thieves demanded a $20,000 ransom, or nearly half a million dollars in today's currency. According to an 1898 article in The Deseret News, detectives assigned to the case made no headway. The ransom was paid, and Stewart's body — or at least a body — was returned. He was reinterred in the Cathedral of the Incarnation in Garden City, New York.

A president vanishes

Tassos Papadopoulos, the former president of the Republic of Cyprus, died of lung cancer in 2008. His body rested in peace in the Deftera village cemetery in the capital city of Nicosia for almost a year — until the day before the first anniversary of his death.

On Dec. 11, 2009, one of Papadopoulos' former bodyguards went to light a candle at the grave, as was his custom each morning, the BBC reported. Instead of undisturbed grass, however, the bodyguard found an empty hole and a pile of dirt. The grave robbers must have done the deed overnight during a downpour.

A telephone tip led police to Papadopoulos' body nearly three months later. It was found hidden in another Nicosia cemetery.

The bizarre body snatching turned out to have an even more bizarre motive. A man imprisoned for murder asked his brother to dig up the former president's corpse, hoping that he could negotiate to secure his release from prison, according to Reuters. But the third accomplice, an Indian national, eventually called Papadopoulos' family and asked for money instead. All three were sentenced to less than two years in jail apiece, as violating a grave is a misdemeanor in Cyprus.

Postmortem Paine

Good intentions only go so far. In 1819, English pamphleteer William Cobbett became disgusted with the uncelebrated burial site of Revolutionary War pamphleteer Thomas Paine, the author of "Common Sense," who had died in poverty a decade before. So he decided to dig up Paine's body and take him back to England, where he planned a lavish tomb and memorial.

"The Quakers, even the Quakers refused him a grave!" Cobbett wrote at the time, referring to the refusal by the religious group to grant Paine a place in their burial ground. "And I found him lying in the corner of a rugged, barren field!"

Cobbett and some co-conspirators set off in the middle of the night for New Rochelle, New York, where Paine was buried, and had the coffin out of the ground by dawn. In England, however, things went off the rails. The funds for the memorial never materialized, and Cobbett ended up keeping Paine's body in an old trunk until his own death in 1835.

It's not entirely clear what happened after that. Various people have come forward throughout the years claiming to have Paine's skull or other bones, but none of those body parts have been proven to be his. An 1847 narrative in the collection of The Thomas Paine National Historical Association on the lost body purported to have traced the bones to a man named Mr. B. Tilly in London; legend has it that some of the bones may have been turned into buttons.

The Bhakkar Cannibals

Perhaps one of the most disturbing reports of grave robbing comes from the Bhakkar district in the Punjab region of Pakistan, where two brothers have been arrested twice for allegedly opening graves and eating pieces of the bodies inside.

Muhammad Arif and Farman Ali were arrested in 2011 and sentenced to two years in prison for disinterring five bodies and eating pieces of them, according to the U.K. newspaper The Independent. A graphic YouTube video purportedly filmed by a Pakistani news station appears to show corpses with missing body parts and human bones in a soup pot.

In April 2014, police arrested the brothers again after a foul smell from the men's home led to the discovery of a disinterred child's head, according to the New York Times. They were sentenced to 12-year jail terms for the latest crime.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus