Nepal Earthquake Toll Only Just Beginning

Terrible as Saturday's earthquake was in Kathmandu, geologists fear more bad news to come as information filters in from the surrounding mountainous countryside which has been cut off from the world by the disaster.

Landslides are certain to have blocked roads and rivers, caused flooding, and may have tumbled entire communities off mountainsides.

“It was the same with the Kashmir earthquake in 2005,” said landslide researcher David Petley of the University of East Anglia in the UK, and author of The Landslide Blog. “Saturday morning, utter chaos. In that case the death toll took a huge jump on Monday when it became clear how badly affected the mountains were.”

Photos: Deadly Nepal Quake Devastates Vast Region

The mountains north of Kathmandu are heavily populated, with terraced fields and villages on very steep, landslide-prone slopes.

"The impact of the earthquake in these regions is going to be dreadful," Petley wrote in his blog on Sunday, in which he also detailed some estimates other researchers have done to quickly assess the landslide.

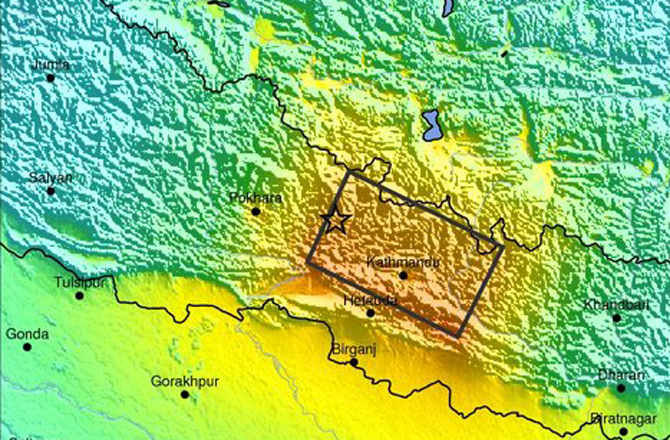

He also points out that there has been a lot of confusion about the area affected by the main magnitude 7.8 event. When the U.S. Geological Survey posted its initial maps of Saturday's earthquake, it featured something rarely seen: a smudge of scarlet indicating the highest, most violent shaking on their scale.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If that was not awful enough, the smudge had swallowed up Nepal's capital, Kathmandu. But the map also had a star indicating that the epicenter of the quake was 50 miles (80 km) to the west of Kathmandu and far from the red smudge.

So why was the worst shaking in and around the city?

The answer lies partly in how the Earth ruptured to make the quake. In this case the epicenter on the map marks where the rupture started, explained geologist and Himalaya researcher Roger Bilham of the University of Colorado. From there the rupture unzipped eastward for 75 miles – right under Kathmandu and beyond.

The Big One: Could a Warning Help?

The fault that this happened along is a lot like those that have created historic mega-quakes in Sumatra, Japan, Chile and Alaska. All are subduction zones, where one plate in Earth's crust is being forced under another. This makes for faults – or "detachments" as they are called – that allow blocks of crust and wedges of material to slide atop one another.

But unlike in those other major big-quake makers, the actual Himalaya collision zone is not deep underwater. "It is inhabited by millions of people," said Bilham. "Nearly everyone in Nepal lives 5 to 10 km from the detachment."

Said another way, all Nepalis live right on top of the detachment, which is deeper in some places than others. That's also why aftershocks are still happening throughout the long rupture zone, including a magnitude 6.6 quake to the east of Kathmandu on Sunday – on the far eastern end of the rupture.

"All the aftershocks are just surrounding Kathmandu," said Bilham. "It's a terrible thing and almost a worst case scenario for Kathmandu."

The other reason the shaking was expected to be worse in Kathmandu than at the epicenter is that the city was built on the bed of an ancient lake. Like most lakes, it filled up with a lot of sand, silt and other soft sediments that were left behind then the lake drained away. Such sediments are known to amplify seismic waves and even liquefy during strong shaking.

Everest Avalanche Victims Rescued During Nepal Aftershocks

The good news, however, is that the USGS backed away from the red smudge as the picture on the ground became clearer. The main shock appears to not have shaken Kathmandu as violently as initially predicted, said Bilham. Backing that up are reports of some fragile buildings that should not have survived are still standing, he said, and that the death toll in the city is not as great as had been feared and predicted by geologists over the years -- which was tens of thousands of deaths.

“It's kind of good news," observed Bilham, "but how much good news is there when the capital of a poor nation is hit like this...."

Petley is also holding out hope that the small bit of good news extends to the areas beyond Kathmandu.

"I am hoping that somehow Nepal has dodged a bullet," Petley said. "Time will tell."

Freelance science writer Larry O'Hanlon also manages the AGU Blogosphere, which features The Landslide Blog.

This article was originally published on Discovery News.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus