A partial human skull found at a site in Kenya suggests early humans living in Africa were incredibly diverse.

The 22,000-year-old skull is not a new species and is clearly that of an anatomically modern human, but is markedly different from similar finds from Africa and Europe from the same time, the researchers said.

"It looks like nothing else, and so it shows that original diversity that we've since lost," said study co-author Christian Tryon, a Paleolithic archaeologist at Harvard University's Peabody Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts. "It's probably an extinct lineage."

The same site also contained deposits that are more than twice as old as the skull, including 46,000-year-old ostrich eggshells that were used to make beads. The new finds could reveal insights about the shifts in human culture that took place starting when the ancestors of present-day humans left Africa, around 50,000 years ago. [See Images of Our Closest Human Ancestor]

Mysterious period

About 12,000 years ago, humans began farming, living in denser settlements and burying their dead, so skeletons younger than that are plentiful, said Stanley Ambrose, an African archaeologist and paleoanthropologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who was not involved in the study.

But relatively little is known about the people who came before them. Only a handful of human burials around the world date from about 12,000 to 30,000 years ago, Ambrose said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To learn more about this lost period of human history, Tryon and his colleagues took a second look at specimens that were sitting in the collections of the National Museums of Kenya in Nairobi. The artifacts were unearthed in the 1970s at rock shelters at Lukenya Hill, a granite promontory that overlooks the savanna in Kenya.

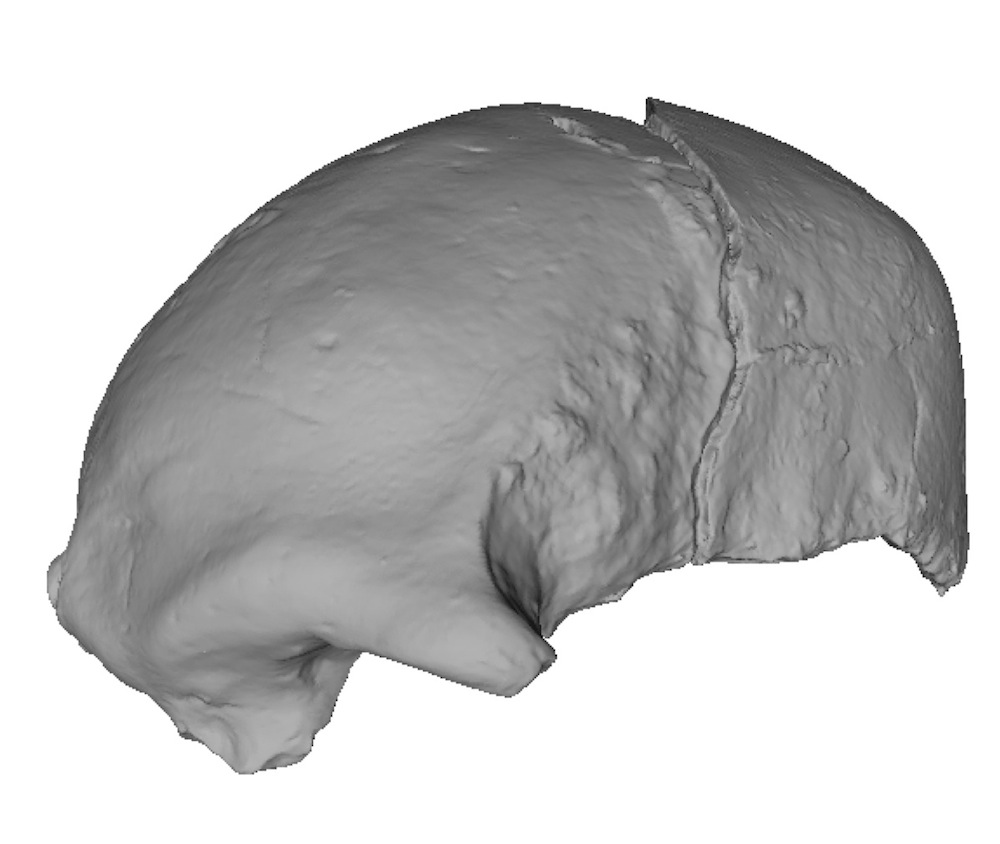

Among the finds was the top portion of an ancient skull. The team took several measurements of the skull, then compared it with skulls from Neanderthals, several other fossil human skulls from the same time and other periods, as well as those of modern-day humans.

Though the skull clearly belonged to a Homo sapien who was anatomically modern, its dimensions were markedly different from those of both the European skull and the African skulls from the same time. In addition, the skull was thickened, either from damage, nutritional stress or a highly active childhood. (There is not enough evidence to say the fossil represents a subspecies of Homo sapien, Tryon said.)

By measuring the ratio of radioactive isotopes of carbon (or carbon atoms with different numbers of neutrons), the team concluded that the skull was about 22,000 years old. That means the ancient human would have lived during the height of the last ice age.

Modern-day Africans have greater genetic diversity than other populations. But the new findings suggest that during this early period of human history, Africa may have supported even greater human diversity, with small, offshoot lineages that no longer exist today, Tryon said.

Light switch moment

Collections from deeper at the site revealed ostrich eggshells, which were used to make beads, as well as tiny stone blades known as Levallois technology. Many of the artifacts were somewhere between 22,000 and 46,000 years old.

The finds come from a dramatic moment in human history.

Around this time, many scientists believe that "this light switch goes on and people get smarter all of a sudden," Tryon told Live Science.

During the period between 20,000 and 50,000 years ago, people began intensively using elaborate trading routes over vast distances, fashioned decorative beads, and made lightweight stone points, that were not much different from arrow blades found in Egyptian tombs dating to about 4,000 years ago, Ambrose said.

"They're very simple little segments of blades that are easy to make, but they're very small and lightweight and they fit into little slots on the ends and sides of arrows," Ambrose told Live Science. "We know that the Egyptian ones had traces of poison on them."

The rediscovery of fragments from Lukenya Hill are important because evidence of human culture from this critical juncture is incredibly rare, Ambrose said.

The Lukenya Hill artifacts were described on Monday (Feb. 16) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.