Death Can't Stop Professor from Getting 'Last Word'

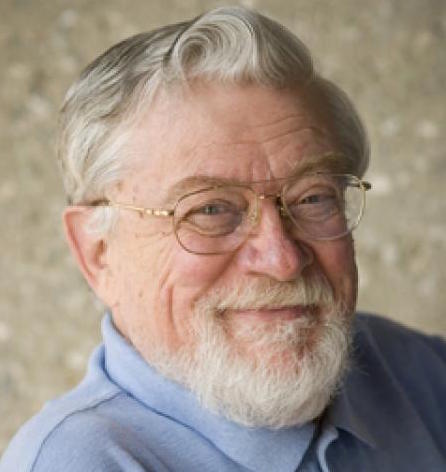

Caltech professor Don Anderson was the first person to unmask Earth's mysterious, multi-layered mantle, transforming science's conception of the planet from a boring, three-tiered baseball — crust, mantle and core — to a gobstobber worthy of Willy Wonka's candy factory.

Anderson's love of science, his sense of fun and his brilliance came together one last time at the American Geophysical Union's annual meeting in San Francisco last week. Anderson had died of cancer at age 81 two weeks earlier, Dec. 2, but he still had the last word. Literally.

On Friday (Dec. 19) at 5:45 p.m. — the timeslot for the final talk on the last day of the weeklong conference, when only the diehards fill seats in dark rooms at the Moscone Convention Center — Anderson was to deliver a talk titled "The Last Word." The topic was a predictably controversial one among geoscientists: that mantle plumes don't exist.

Anderson has long been the most prominent leader of a small band of scientists who pooh-pooh the idea that there are plumes within the Earth's mantle. Such plumes are thought to be long, narrow columns of hot rock that rise from deep in the mantle, near Earth's core, and pool in the upper mantle, feeding "hotspot" volcanoes such as those in Hawaii, Iceland and Yellowstone. A winner of the National Medal of Science and Sweden's Crafoord Prize for mapping the interior of the Earth, Anderson said the mantle plume model defied the laws of physics. Instead of ascending blobs, Anderson and like-minded colleagues said shallow hot zones in the mantle supplied volcanoes.

Despite the years Anderson spent needling other geologists about the evidence for his ideas, mantle plumes remain a popular model for explaining many of Earth's volcanic features. [Photo Timeline: How the Earth Formed]

"We haven't had too many people change their minds, but it's going to happen," said Anderson's friend and colleague Jim Natland, a petrologist and emeritus professor at the University of Miami's Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science. "Don will be remembered as instrumental in that."

The talk's title was typical of Anderson's attention-getting style, Natland said. The event was scheduled after Anderson's diagnosis, but before his health rapidly declined, Natland said. "He hoped to be here."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Anderson was head of Caltech's Seismology Laboratory from 1967 to 1989, years that encompassed the plate tectonics revolution. Though he brokered no fools when it came to substandard science, Anderson generously gave his time to students and colleagues. He zealously guarded the Seismo Lab's coffee hour, an informal gathering at which scientists could chew over problems with co-workers. Anderson was also a prolific reader and writer, mastering geophysics and geochemistry and publishing a seminal textbook called "Theory of Earth" (Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1989).

In diving in to such a wide range of topics, "he basically did the opposite of what science said to do, which is get more specialized," said Bruce Julian, a retired research geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, California, and one of Anderson's first graduate students.

Though Anderson missed the opportunity to present his last words in person, he did spend the final months of his life directing his legacy. Soon after his diagnosis, Anderson emailed half-finished manuscripts of papers to colleagues, hoping they would polish his final insights on how the Earth works and publish them in journals. The scientist directed relatives to update his Wikipedia page, said his friend Gillian Foulger, a frequent collaborator and a geophysicist at Durham University in the United Kingdom.

"When he realized he was going to pass away, he rallied the troops," Foulger said. "He had all these senior scientists working as [if they were] his postdocs," she said. "It was like he was director of the [Caltech] Seismo Lab again. He had a ball."

Between the flurry of recent papers, a planned book in Anderson's memory and the AGU memorial session, the renowned scientist certainly managed to have the the last word, his friends told Live Science. And instead of mourning his absence, Anderson's friends and family popped open champagne and toasted his memory Friday afternoon, Foulger said. "Science wouldn't be where it is today without him," she said.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.